History carved in stone at Greenhill Graveyard

From East Texas Journal, October 1993

By Hudson Old, Journal publisher

Greenhill, Texas – Minutes of the Presbyterian session at Greenhill, September 12,1860, tell of the church’s founding by pastor E. H. Green, 13 laymen and “the following named servants.”

With its beginning in a backwoods brush arbor, the congregation built its church in the years 1870 to 1872, a white clapboard country church that today sits beside a sleepy oil-topped road overlooking a cemetery that predates the building by a decade, located 7 miles north of Mt. Pleasant off Farm Road 2152.

“It’s said that the first grave in the cemetery belongs to Moses Rose,” said C.S. Hays, whose father, A. Z. Hays, taught at an early Greenhill school.

“My dad got the story from Charles Black,” a 19th century farmer. Moses Rose, the main history says left the Alamo when Commander Travis asked those who would stay to cross a line he drew in the dust with his saber, is believed to have established a freight line at Many, Louisiana after the Texas Revolution. Passing through the Greenhill community along the Clarksville to Jefferson Road, he became ill and stopped at the Charles Black farm, Mr. Hays said. When he died, Mr. Black refused to bury him in his family cemetery.

“My dad says Mr. Black told that story on himself,” said Mr. Hays, born in Titus County in 1906. “That same year, Mr. Green had started the church and figured that since he’d started a church, he might as well have a cemetery to go with it.” The story leaves room for debate, said John Johnson, a member of the church’s cemetery board and its grounds keeper by acclamation.

“In Many, they claim he’s buried there,” So, when the cemetery board decided to replace the original grave marker, a rock, they simply carved on the stone that the cemetery’s first grave belonged to an unknown traveler.

“One irony about the incident,” says Mr. Hays, “is that one of my great-great uncles, Reason Hays, and a man named John Barton dug that first grave. Their graves are the second and third in the cemetery.”

Entire families trace their Texas heritage back to Greenhill, recalling the community’s thriving days at the turn of the century, snippets of history etched in the stone markers of the cemetery.

It’s partly a history of the Texas frontier, recognized for its importance nearly 100 years ago. In 1908, a cemetery committee was appointed to investigate “the fact that Jack Barton was a survivor of the Goliad Massacre, as had been stated he was,” reads an aging Titus County newspaper account.

There’s a considerable number of Freemans buried here, descendants of a Georgia native and boy civil war soldier, twice wounded, who spent four years fighting before being set adrift in the reconstruction

South. In the late 1880s, he came to Titus County, settled at Greenhill.

By the 1890s. Texas — one of the state’s least disturbed by the Civil War — had made a good recovery.

Greenhill was a beacon — a community of prosperous farmers. By the mid 1890s, after buying 300-odd acres at Green’s Hill, John L. Freeman built a small mule powered cotton gin. Shortly thereafter, he built a steam-powered gin. Using power from the engine’s main shaft, he built a sawmill, shingle mill and grist mill.

He went into the cotton seed storage business, and arranged an auger system beneath his four gin stands, designed to deliver seed to the wagons of his waiting customers.

The original gin he built was sold to a Mr. Rogers from New Mexico.

All this information comes from Rhodney Freeman, John L.’s great-great grandson. Born during World War II, Mr. Freeman has vivid childhood recollection of the old gin, closed by then. But he played in its shade as a child, and as a man has taken time to write down what he can recall of his family, interview his older relatives and ferret out the census records and war records that trace John L.’s life.

His research runs a community gauntlet, tells of the heady days when its citizens envisioned a town. There was a barber shop, two grocery stores, the gin, the Methodist and Presbyterian churches, grist mill, dripping vat, blacksmith shop. In 1907, according to Titus County deed records, L.A. Hall and W.W. Woods donated some 20 acres of land for a town site, a railroad right of way to bring timber through the community to the Hoffman Heading Mill in Mt. Pleasant.

The land was laid out, with eight city blocks designated.

The town never materialized, but the spur line came through and in 1912, the Paris and Mt. Pleasant (Ma & Pa) railroad came through and a small station was built at Wylder Switch.

John L. Freeman, the story goes, was a bear of a man, over 6 feet and some 250 pounds. The gin pond he dug still exists, just on the west side of FM 2152, which winds through the country there. He died in the winter of 1918, but his sons, John V. Freeman, Miller and Marion continued to operate the gin into the late 1930s.

There’s still Freeman land here.

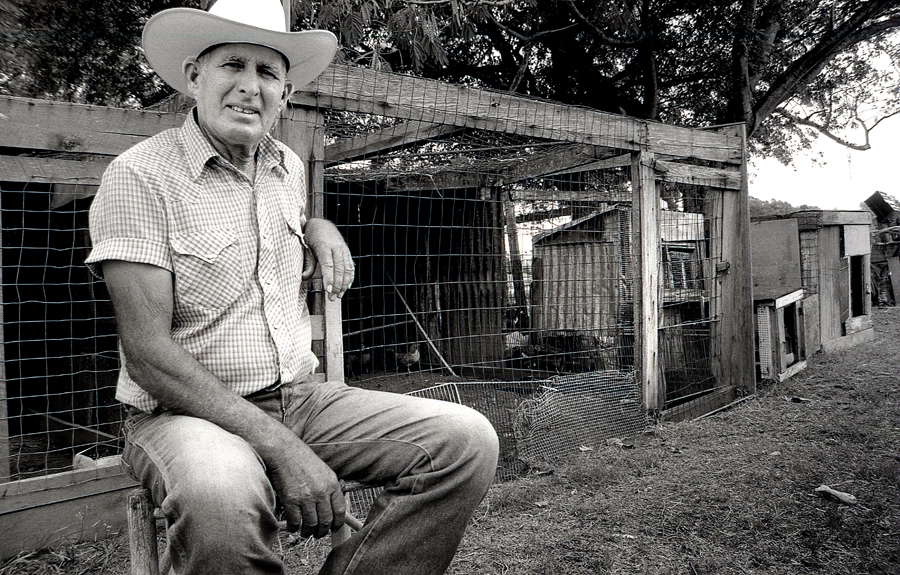

On the west side of the farm to market road, down a little lane that no doubt once tied in with the lane on the farm road’s east side, leading past the old Presbyterian Church, there’s a modest and tidy place, a trailer sitting back on a manicured lawn.

Walter Freeman, retired from the county, lives here with a little slick-haired, lap-sized terrier dog. Out back, he’s got a string of chicken coops, pens built tidily, framed up with whatever was at hand, sheltered with rusting sheets of galvanized sheet iron. He keeps bantams and game cocks, just because he likes them, and had a milk goat until she recently died.

He grew up in a farm family, remembers riding to school on the bus his grandfather, J.V. Freeman,

and R.C. Hill built on the back of an aging truck previously used to haul cotton seed.

At the state fair, he once saw a bullet-riddled ’34 Ford being passed off as the car famed outlaws Bonnie and Clyde were driving when they were gunned down.

“All I can tell you is, that car was a four door and the car they were driving when they came through Greenhill was a two-door coup — had a rumble seat” Walter said.

He saw them at either Cool Springs or Black Cat Inn, a couple of early-day saloons that served the community’s drinkers.

“My grandpa used to carry me with him whenever we went to Mt. Pleasant to sell cotton seed, and generally, he’d pay a social call at the saloons,” Mr. Freeman said. “It was an education for a young boy — it was one of those days that I saw Bonnie and Clyde here.”

There’s not much sign of the near town that was once here — the land on the south side of the county road going by Mr. Freeman’s house, all the way to the Mt. Pleasant city limits, is scheduled to be

mined for coal. It’s mostly sold out, the families moved on.

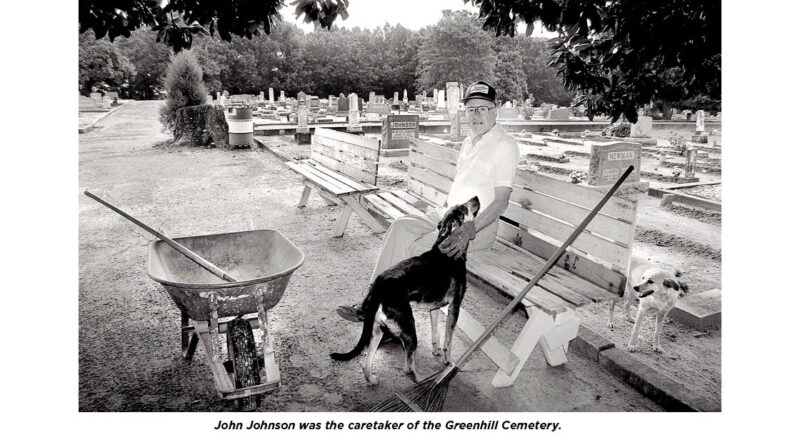

I found John Johnson at the cemetery, early on a late-summer morning. As caretaker, he keeps the whole place — maybe an acre – flat hoed, devoid of grass, neatly raked. Every grave is mounded.

He had out his tools — rake, wheelbarrow, how and a file –.

“Keep your hoe sharp, why hoeing’s not such a chore,” Mr. Johnson said.

“Even this much?” I asked.

He chuckled, led the way to a white park bench, set in the slick-leafed shade of a mammoth magnolia tree.

“We’re lucky out here,” he said.” In 1955, a woman named Tess Hood-Maley died and in her will endowed the cemetery. She had no heirs — maybe some distant kin up around Dallas.

“Her only stipulations were that we use a part of the money to drill a deep well and put roads and curbs through the cemetery. It needed ’em. The way this thing sits on a hillside, it tends to wash — the curbs slowed that way down.

“First, we tried keeping it clean with big volunteer groups. Then we hired a guy and another guy and finally another guy — I got disgusted just watching them. I don’t guess you can hire anybody to hoe anymore.”

Finally, in 1983, Mr. Johnson and his son, Billy, took on the job.

“I’ve got an interest in this place,” Mr. Johnson said, pointing to a row of “Johnson” markers just

behind him.

“That one there,” he pointed, “Dr. William Russell King Johnson, 1854 to 1928 — that was my grandpa. He drove a horse and buggy — I can remember him catching his horse and hitching up his buggy up in the middle of the night. My grandmother would try to get him to just send medicine to a patient’s house — he never would.”

Retired now, Mr. Johnson said he enjoys spending the cool part of the morning working in the quiet of the cemetery.

“About three times a year, the whole thing has to be hoed — that can get to be hot work,” he conceded. He was quiet for a moment, then told me his sister-in-law had died suddenly the afternoon before. This particular morning, he’d come up to make the cemetery look as nice as he could for the burial.

“You know what’s really nice?” he asked. “It’s nice when a little shower comes up to come sit on this bench under this magnolia tree and just listen to the rain. You can sit out a pretty good rain right here, never get wet.”