Hear-say evidence nails Civil War prisoner’s descendant

HICKORY HILL – What evidence we got here wouldn’t hold up in court, but it’ll do fine for a story based on a 1993 interview with the late Betty Hargrove-Hollingsworth, who is in no position to dispute the report.

Among her treasures was a xerox copy of a family history, written by a woman out of Missouri. This woman and Betty could both trace themselves back to a man named John Keeney.

A sentence in this history says: “According to family legend, John Keeney may have ridden with Quantrill.”

Written in ball point ink behind that is this sentence: ” It has now been proven that John H. Keeney rode with Quantrill.”

There you have it, in black and white.

The catch here is that Mr. Quantrill found it advantageous not to leave written records concerning all his activities and all his cohorts.

However, right after the Civil War, John N. Edwards, editor of the Sedalia, Missouri Democrat wrote of William Clarke Quantrill:

“He was a living, breathing, aggressive, all-powerful reality, riding through the midnight, laying ambuscades by lonely roadsides, catching marching columns by the throat, breaking upon their flanks and tearing a suddenly surprised rear to pieces; vigilant, merciless, a terror by day and a superhuman if not a supernatural thing when there was upon the earth blackness and darkness.”

What Betty did have some records on, though, was the time John H. Keeney served as a prisoner of war during the winter of 1862-63, through the spring. She’s got the papers, showing when and where he was captured and when he was released. She’s got a copy of a letter he wrote home in which he praises the efforts of his son, Luther, for getting a crop in. Luther, who was about 11 then, would later serve as Titus County district attorney, and we got the goods on him for sure.

The afternoon we visited, Betty produced, from her cedar trunk archives, a yellowed and brittle newspaper clipping from an ancient newspaper telling about “outlaw” Cole Younger’s visit to the home of Titus County District Attorney Keeney.

Dusting the cobwebs off history, you’ll recall that the slavery issue spawned border wars and raids between Kansas and Missouri even before the War Between the States.

Younger’s outlaw roots began when he rode with Quantrill.

Depending on who you read, Quantrill and his irregulars were credited or accused on two occasions with butchering the entire citizenry of Kansas towns. You can color the story with tales of equally vicious attacks by irregulars fighting out of Kansas.

Cole Younger, writes biographer Carl Breihan, was a man of high Missouri breeding. His father, an elected official, was killed by federal troops. His mother was forced to burn the family home in the dead of winter, Breihan writes, and thus did young Cole sign on with Mr. Quantrill’s guerrillas.

Missouri developed a sympathy for its outlaws. After the war began, Frank James joined the Confederate forces. He was captured, but given a “field parole” for vowing never again to fight the Union. He defied his parole by joining Quantrill’s guerrillas.

His stepfather was hanged in retaliation; his mother and sister jailed. Little brother Jesse James was badly beaten.

Jesse James signed on with Quantrill.

It was years later that Cole Younger came to visit Luther Keeney, the Titus County DA who’d plowed Missouri fields while his father was a prisoner of war.

Mr. Keeney had a beautiful daughter by then, a girl who’ married Mallard Hargrove, Betty’s grandfather. The Hargroves were sawmill people, a family that harvested the forests of east Texas for the better part of a hundred years. They settled a few miles southwest of Mt. Pleasant.

The old newspaper didn’t have a lot to say about Mr. Younger’s visit with Mr. Keeney.

The event merited this item: “Cole Younger, the Missouri outlaw, recently visited the home of Titus County District Attorney Luther Keeney. As a boy, Mr. Keeney hauled water to Mr. Younger when he rode with Quantrill’s guerrillas.”

Not much of a mention, but it’s all there if you read it close. Mr. Younger was an old man by then. It’s said that Quantrill was too hard a man for him; Mr. Younger gave up being a vigilante and went into bank robbing, a career that eventually earned him 25 years in a Minnesota prison. Mr. Keeney had come from Missouri with the broken pieces of his family after the war – – he’d put together a new life in Titus County with a successful law practice and a daughter who’d married well.

The arrival of Cole Younger to visit the family would have caused a stir; a big spread for dinner with all the family about, then recounting the days of the war while visiting in the parlor, and later, spending the cool of the evening out on the porch where young Alice Keeney-Hargrove could have listened to the men’s stories far into the night.

” I grew up hearing my grandmother tell those stories,” said Betty Hargrove-Hollingsworth.

That’s where Betty’s got her first-hand oral family history accounts of her great-great-grandfather’s days with Quantrill.

Alice Keeney Hargrove’s husband, Mac, thrived as a second-generation timber man here.

“My dad helped my grandfather Mac build the first bridge over the Sulphur River so they could bring timber out of there for the Hoffman Heading Mill in Mt. Pleasant,” Betty said.

By the 1940s, Betty’s father had moved to Anderson County and set up a sawmill there.

“One of my earliest memories is a team of twin draft horses daddy used to snake timber out of the woods ~ Ben and Dan,” Betty said. “One Saturday — maybe I was three –I got to go to the woods and watch them – if one of the horses quit working, his brother would reach over and bite him.”

Thanks to National Geographic, the Hargrove family made written history.

The story was in the October, 1974 edition. It portrays the rustic, wholesome, backwoods life of your sturdy sons of pioneers, some swamprat descendants preserving a way of life, if not an entire ecological system, the article implies, by living, hunting and fishing down in the big thicket.

At the time, a battle brewed between a handful of timber companies and conservationists over just how much of the Big Thicket should be preserved in its natural state.

The Hargrove family was portrayed as the villains – sinister loggers. To prove the point, the National Geographic made a picture of a Big Thicket debutante and her brother, standing armed guard with a long shotgun over a skinny hardwood with a big sign nailed on it:

“All FISHERmen HUNTers and ALL OTHER LIERS ARE WELCOME,” says the sign, “BUT HARGROVES and his men Keep Your (Explicative, delete) Off!”

There were equally illiterate quotes from the Big Thicket people aimed at the timber people.

“I’ve kept care of the land, I’ve kept care of the timber,” the magazine says this guy said. “This is my whole life. It’s mine, and nobody’s gonna take it from me, not as long as I draw breath and gunpowder burns.”

It was good reading, but Hargrove and his men went ahead, went to the woods, went to work, and brought out the timber.

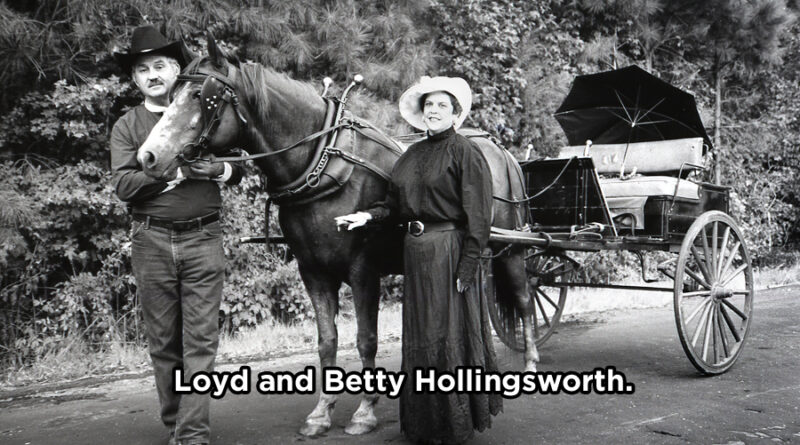

Betty and her husband Loyd made their home in the Hickory Hill community, down in the southeast corner of Titus County. He worked for the Welsh Power Plant; both he and Betty volunteer considerable hours to the sheriffs department auxiliary and the Titus County Sheriffs posse.

“Loyd’s the last charter member of Sheriff John’s Posse,” Betty said, and she was the secretary-treasurer of the auxiliary.

“Outlaw decedent and holding the purse strings,” she grinned.