Soldier with music brought a song to the war

In the relative comfort of the second floor of a school building still standing in Tientsin, China, one day after the Japanese surrender, 21-year-old South Pacific veteran Eddie Hammond and some buddies pooled resources and bought a $4 guitar.

“I was sitting in the door playing and another guy turned chopsticks into drumsticks and a tin cup into a drum and played with me,” Mr. Hammond said. Guards on the first floor allowed only Americans in the school building.

On the street below the windows, Chinese civilians desperate for money called up to the Americans, displaying things they might sell. Besides a guitar, Mr. Hammond made a deal for a fresh egg. Somebody smuggled up a bottle of hooch.

A 55-gallon drum full of water served as the fire extinguisher for the improvised barracks.

Mr. Hammond and his drummer took a break with the rest of the platoon draining the liquor reserves. Thinking collectively, troops challenged to determine the best way to destroy the evidence decided to sink the bottle in the fire suppression system, which to Eddie Hammond was a moment as entertaining as the music.

“The way that jug swirled as it sank,” he remembered, “it seemed like I’d never seen anything quite like that.”

(Clearly, this isn’t the observation of a practicing drinker.)

Prevailed upon to remember China – or anyplace else the stream of conversation turned — he said music had more value when it was harder to come by. Back in East Texas before radio, after the harvest his father traveled teaching 2-week music schools. People put him up and paid to boot to send their children. Churches anchored his teaching. Nothing fancy, just how to run scales and find chords on a guitar or a piano, enough to steer the tune of hymns and country songs.

“What music I know, I learned mostly from my daddy,” Mr. Hammond said. He’s been practicing for 80 years since. He writes some music. A musician named Henry King has recorded some of his songs. A Sulphur Springs DJ at KSST-AM radio plays his music on her radio show.

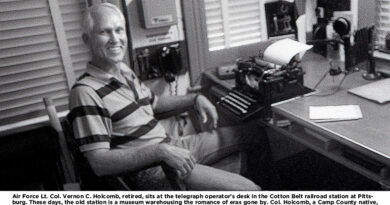

In life order, he’s been a farmer, a soldier, a telegrapher, a rail station agent, a steel worker and a writer. Years back, he wrote stories about what he knew about World War II for a military magazine in California.

In one story he remembered the bodies of Japanese infantrymen who died with a wrist chained to the gun turret of tanks that had come charging into the battle for an airfield at Peleliu, a sliver of Pacific coral island a half mile wide and seven miles long.

An overly-optimistic American command projected a beach landing securing the island and its airfield within four days. It took 43. The 1st Marines suffered some 6,500 casualties, one third of the division. Not counting 183 slave laborers captured by Americans, 19 Japanese defenders surrendered and another 10,695 fought to their death.

“Years later I visited with an Army soldier who had survived the Bataan Death March,” Mr. Hammond wrote in his first magazine piece. “He spoke of how he came to know some of the Japanese guards at the encampment and said he’d like to see some of them again. That sounded strange to me and I thought, ‘this soldier who was close to and understood these peculiar people might answer my question concerning the soldiers chained to their tanks.’

“They didn’t want to go,” he said.

His story about the battle for Peleliu described by the Marine museum as the most “bitter” of the war made him modestly famous among Marine historians who put an emerging writer in touch with other veterans.

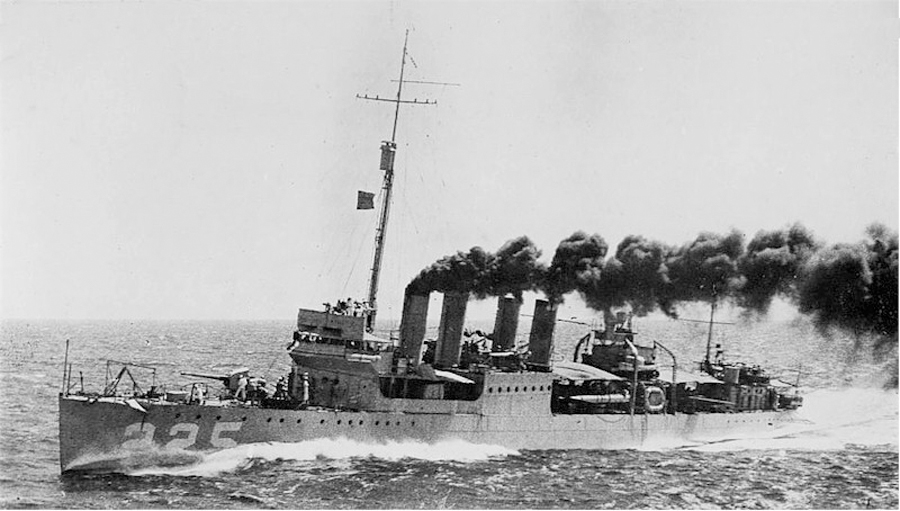

One letter came from a sailor who’d been aboard the destroyer USS Pope when it was torpedoed in the Java Sea. After 60 hours adrift in life jackets, he was one of the survivors still afloat when the Japanese found them. As a prisoner of war, he risked beating or worse when he stole a pad and pencil. It seemed important to have some record. He hid his diary in the hollow of a bamboo post.

Starving, he was among those volunteering for extra work in a cement factory in turn for an extra piece of fish.

“Sure getting bad,” he wrote four days before Christmas, 1944. “Limeys are eating baked worms. Yard Dog Smith caught another dog which we ate on a Sunday (I think) three weeks ago. We are going to try to get coconuts during guard change at 3 a.m. tonight. Rope and hook are ready.”

A year passed.

“Boogie Smith died today,” the sailor wrote in the spring of 1945. It was April. “Gotta help dig grave. Sure gonna miss that old boy.”

Besides the 1st Marine casualty rate at Peleliu, the highest of any island landing in the Pacific, the battle was bitter in retrospect because the air strip the Americans ultimately secured never came into play in the larger theater of the war. The island-hopping American drive across the Pacific toward Japan had leapfrogged ahead by the time it was over.

Leapfrog ahead 60 years in time and the battle became the basis for a killer on-line video game. In the first of the “Call of Duty” trilogy, players are transformed to Marines fighting across a beach to storm across an airfield. The final assault was against defenders inside a network of 500 caves connected by tunnels inside the Umurbrogol Mountain Fortress.

Between 2003-06, the video game grossed some $8 million in sales.

Back in the real world, unlike the defenders’ “Banzai” charges in the initial island landings, at Peleliu Japanese Commander Kunio Nakagawa prepared for siege. He blew holes through the network of caves under the mountain top and set up artillery with a seamless field of fire overlooking the airfield and two miles of beach below “Bloody Nose Ridge.”

“Tenno Heika Banzai!” had been a Japanese battle cry for those commanded to charge into the face of certain death, human waves of counter-attacking island defenders. At Peleliu, Commander Nakagawa prepared for a war of attrition.

That worked. The defenders were virtually unscathed by three days of bombing and shelling in advance of the landing, says the on-line source Wikipedia. The landing began after sunrise the morning of September 15, 1944. Within the first hour, the Japanese sank 60 American landing craft without suffering a casualty.

Air conditioner humming in the kitchen window, 94-year-old Eddie Hammond sat in his recliner with a sheaf of papers atop a book about the war in his lap. A stand by his chair held his guitar within easy reach.

The papers were clippings from three of the war stories he’s written. There were copies of letters from soldiers, Marine historians and a photographer named John Smith who captured one of the most recognizable frames from World War II. Mr. Hammond opened the book to the picture of a landscape bombed into raw dirt and skeletons of burnt trees. The backdrop is alive with soldiers now frozen in time, then sweltering in the earth beneath a rain of mortar and artillery fire coming from the mountain. The heat index hit 115 degrees that afternoon.

Mr. Hammond’s platoon is in the famous photograph taken by John Smith, who wrote him a letter after Mr. Hammond’s stories made him known, particularly among those who’d served in the South Pacific.

“This is a real treat,” Mr. Smith wrote concerning Mr. Hammond’s recollections and connecting with one of the men in his photograph. “This picture has been called one of the ten best from the war.”

In the first 30 hours following the landing, Marines fighting across the beach to the landing strip ran out of water as they burrowed into the earth at the foot of the mountain.

Listening while I read from his stories and correspondence, Mr. Hammond remembered, “Some way, Brown got hit in the back as we were coming in and it blew his arm up on the beach in front of me.”

That wasn’t in his stories. It was just something coming to mind. He’s written the names of the men he recognizes in the picture. He couldn’t remember right away where Stan Bender, Gene Coburn, Jim Young, or Robert Henderson might have been from.

In that his troops held their mountain-top position for 43 days, Commander ____ successfully defended the airport long enough for the larger war to pass by. Rather than surrender, he burned his regimental colors as the relentless American Marine assault depleted his resources and ability to wage war.

“Our sword is broken,” he wrote, “and we have run out of spears.”

In keeping with the ancient code of Japanese warriors, rather than surrender he committed ritual suicide.

In Mr. Hammond’s living room, I asked questions leapfrogging him back and forth through time, as if time were a mountain range where he might land on any peak he’s climbed, any valley he’s crossed.

I asked what songs he played with the $4 guitar.

He didn’t remember, right then.

He did remember Japanese tanks racing across the airfield breaking an afternoon lull in the turkey shoot and afforded invading Americans their first real targets for the day. Ready for the chance, the Americans knocked out tanks with such efficiency that the Japanese counter-attack retreated. They left behind the body of at least one sniper who’d provided what cover he might for infantrymen advancing with the tanks.

Mr. Hammond, who was 20 back then, went zig sagging up to a bomb crater and took the rifle of the sniper who’d died there. Later, he mailed it home to Texas. Some weeks later, it seemed an amazing thing to get a letter from home saying that an enemy soldier’s rifle had arrived back in Hopkins County, delivered at the family farm by a rural route carrier from the post office at Brashear.

“Think of that,” said Mr. Hammond, who is just as affected by that success now as he was then. He sat silent for a moment. I read again, a letter from an archivist at the Marine Museum near Quantico, Virginia.

Done with the war for the afternoon, Mr. Hammond said back in Brashear he and his father typically had 54 of their 93 acres in cultivation, 40 acres of cotton for cash and 14 acres of corn to feed two teams of mules and a half dozen Jersey cows they milked. He said farm families traded and bartered as much as they might, always holding on to their cash as long as they could.

“The joke was you could trade a brush pile if you promised there was a rabbit in it,” he said. A rabbit was an extra meal.

He was in his teens when the local Rural Electric Cooperative was created, rode by, rolled off a light pole and strung wires back to the generating plant. The Hammond family went into debt, buying a $48 refrigerator they paid out.

“I’ve still got it out in the barn,” he said. “It still runs.”

He traded once for a wagon that belonged to an old timer in Sulphur Springs who’d used it to transport men from Hopkins County to enlist and ship out from Mt. Pleasant during World War I. He’s still got it, too.

“It’s got a wheel I need to fix,” he said.

Out on the lawn, he’s got his mother’s wash pot. Before running water, they drank from an underground cistern collecting rainwater and drew wash water from a bored well. The water from the well wasn’t fit to drink but was fine for boiling clothes.

“She washed on Tuesday,” he said.

He once dared dream of somehow earning a living with music. He bought a little land on a high point in rural Cass County. He made a front porch on a cabin for a stage and built a primitive campground. He called it Music Mountain and for a while musicians came and played and enjoyed the fellowship but it never turned into anything a family could live on.

Arriving with a flood of soldiers returning from the war, he went to school for six months and learned Morse Code and typing, which made him a railroad telegrapher in New Mexico. He was promoted to station agent before coming back to visit East Texas where he found better work at Lone Star Steel.

He bought 20 acres his home near the Titus-Morris County Line.

He flies the American flag every day.

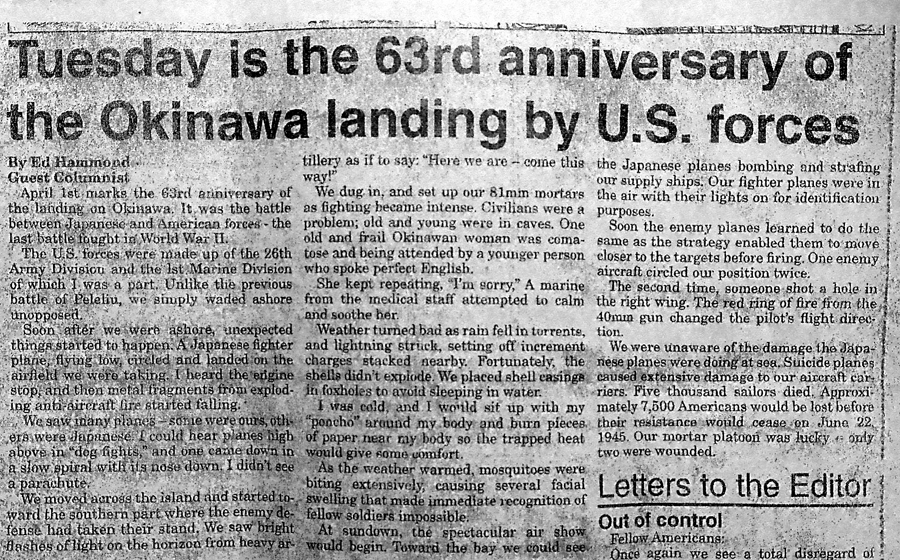

He was in other battles after Peleliu – Okinawa was one. If anything redeeming, anything good came of Peleliu, it continues to escape him.

Nearly a quarter century back, he wrote a sentence quoting a private that he claims as the smartest thing ever said:

“As I enter the twilight of my life and think of Peleliu, I think of a private who was supposed to have said, “If there’s anything stupider than war, I’d like to see it,” he wrote back when.

Turning his thoughts back through time, I asked if he remembered what music he’d played in China when they sank the empty bottle of hooch in the water barrel.

He shrugged, smiled, picked up his guitar and answered as suited him.

“Oh beautiful, for spacious skies,” he sang, strumming into America the Beautiful.