World War II through the lens of a surgeon with a camera.

By HUDSON OLD

Journal Publisher

MT. VERNON – Listen: “I remember moments disconnected from the larger picture of the war,” said Dr. Jabez Galt, valedictorian of the Mt. Vernon High School class of 1935. Through the years of World War II he was a battlefield surgeon.

His family had a pecan orchard here. After the last of them were gone, each year Dr. Galt gave whatever profit the orchard made back to Mt. Vernon.

After the war, he opened his practice in Dallas.

In the diary he kept during the war, he wrote of arriving Italy, coming ashore on the isle of Capri, a civilized evening at an old hotel in a village with cobblestone streets.

“My room was so inviting that I was tempted to stay there, but in a moment dismissed such an absurd notion and went down to the bar. This retreat was easily located due to the bedlam ensuing therefrom.”

He wrote of meeting infantrymen and pilots, being immediately taken in and disrespectfully nicknamed, relishing the night.

He was a soldier in the alternate universe of a musical spell that night.

“Disdaining the impotent drinks served at 40 cents a throw by two costumed, well-hipped beauties, I poured up prescription whiskey and then went into the area where an old man was tuning a piano. ‘Papa’ in his smock had a bald head, his face composed of large glasses and thin-parted lips bordering very false teeth. Thrilled and humbled that I should ask him to play, his gnarled hands skillfully brought Chopin into the lounge with us and his body swayed with music transforming the moment to a far away place as the tinkle of glasses and the murmur of voices grew ever distant.

“After a well-camouflaged dinner of GI food, we toured gardens along a walk bordering the cliff over the seas. Some saxophone player of poor ability but much enthusiasm followed us, causing spontaneous streams of dancing with our nurses, and a few others,” he wrote.

Later, he wrote of soldiers bombed into lunacy, of events testing the limits of compassion.

“All I can do is follow the orders given me, but how can I talk these men out of their neurosis and send them back to the war and untold misery if not probable death when I don’t know why we are here?

“I am writing dispassionately for I have passed the stages of frustration, grief and near despair. I hope that I will never again be forced into my present apathy.”

In moments he railed against the “bull-headed stupidity” of military command showing “no respect for authority of heaven or earth.

“Last night the heavy stuff roared and rumbled from the front where muddy hell is loose. Its casualties are tired out, battle weary, under-clothed young men who fight only for self preservation until the next challenge to their lives – yet on the wards in response to my question of who wants to go back to the front, 30 got up. A soldier named Bruno was typical of any Italian American warming himself at the stove before leaving. He said, without heroics, ‘They killed two of my buddies in the signal corp and I’m going back to kill all of them I see.’

“Our chaplain isn’t smart enough to preach to me with conviction, or even to avoid ridicule. For men who have lived in hell itself and just happened to come through, today he preached an absurd sermon of straight-laced fundamentalism against drinking.”

Fifty years after the war, he found letters he’d written home, saved by his father and sister.

This story comes from his diaries, those letters and an interview in the spring of 2001 when he returned to Mt. Vernon for a concert at the old depot where he once caught the train taking him away from his last visit home before the war. He was fresh out of Baylor Medical school.

In his diaries, he wrote of the war. In his letters, he wrote of the people.

“My dear Liz (his sister) and Dad,

“Christmas slipped in and out so pleasantly, but a strange happiness of nostalgia and pathos that tends to leave emotions depleted, human and pathetic seeing these battle-weary fellows who have gone so long hoping for the next day, now sitting up on cots with scissors and paste and salvaged colored paper, bright dyes made from medicines, bandages, sprigs of green stuff and all the enthusiasm and eagerness of kids back home making garlands . . . the ambulatory ones gathered around a pot bellied stove helping nurses make candy . . .”

The evening of the concert back in Mt. Vernon, the railroad had long since abandoned the depot. Dr. Galt had given the first $20,000 for its restoration as a museum by the Franklin County Historical Association. Players from the string section of the Fort Worth Symphony played the works of Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms. Dr. and Mrs. Galt sat on the front row and he closed his eyes as he listened.

Years passed. In July, Dr. James L. (Jim) Borders brought his wife here to visit Dr. Galt’s hometown. As a young internist fresh out of Baylor, he joined Dr. Galt’s Dallas practice in 1982.

Dr. Borders was playing piano at a jazz venue back in their native Kentucky when his wife discovered him. A musician, he is also now Chief of Staff for the 625 physicians at Baptist Health in Lexington.

“He didn’t tell me he’s a doctor until our fourth date,” said Karen Borders, who up until then had connected mainly to his music.

Dr. and Mrs. Borders live in the country where he gardens. Before leaving for Texas, he finished writing a piece for a medical quarterly. She finished canning a crop of green beans.

“Physician Musician,” reads the title of the article he wrote for the summer edition of KentuckyDoc, a story opening with a saxophone player leading a six-piece jazz band featuring the doctor on keyboards.

In his analogy, music and medicine are two sides of the same mind. Each lends value to the other.

The Border children have emerged as artists. The son is a sculptor, the daughter an actress.

Dr. Borders sees art as a portal, an example of common ground with the capacity to connect people.

“American society undervalues art,” he said. As the student representative serving the Baylor Medical School admissions committee his senior year, he asked prospective students if they had two lives to live and one were medicine, what would the other be?

“’The other would be medicine, too!’ was a disappointing answer for me,” he said. He believes medical school curriculum should sharpen its focus on lives beyond medical practice, nurturing avocational interests enhancing interpersonal skills to engage and counsel “each patient as a unique and interesting individual.”

He found that nature personified when he joined Dr. Galt in the Dallas practice where he spent six years.

“Dr. Galt routinely performed what we called ‘biopsies of character,’ getting a sense of a person in an instant by observing subtle things that would be insignificant to less discerning students of humanity,” Dr. Borders said. “The thing making a physician his best is seeing the whole of his patient.”

Dr. Galt was tall, over six feet. He could be as prickly as he was genteel, Dr. Borders said, slipping into a story about an unknown and buxom woman on an elevator being too obviously smitten by no more than Dr. Galt’s presence, to the point of offense.

“How tall are you?” she wondered dreamily.

“How much do you weigh?” he answered.

He had similar consideration for telephone solicitors.

“I always pray before making any decision,” he said in answer to any phone pitch. “Please, won’t you bow your head and join me?”

As guests of Mt. Vernon attorney B.F. Hicks, a relative of Dr. Galt’s, Dr. and Mrs. Borders spent four days exploring from Mt. Vernon to Caddo Lake.

“I’d never seen Texas except from an airport,” she said.

He spent time thinking of Dr. Galt’s manner as a physician while thinking of his upcoming key note delivery before a state-wide gathering of Kentucky doctors.

Tipped off, I caught up with Dr. and Mrs. Borders at the Mid-America Flight Museum in Mt. Pleasant. Titus County Deputy Wayne Minor was charming Dr. Borders with explanations of the technology of the museum’s vintage “war birds.” Dr. Borders is a model plane pilot with a rising interest in drone photography. Deputy Minor is a pilot, a photographer and a historian, a Saturday-morning museum docent. The lawman and the doctor hit it off.

“Everyone’s so cordial,” said Mrs. Borders, discovering Texans of praise-worthy deportment.

When Dr. Galt made his last call in Mt. Vernon, I went to hear him speak at the high school, then at the Rotary Club luncheon before the evening concert.

In his address at the school, Dr. Galt read from the Christmas letter, leaving out mention of a soldier who’d died while others made candy with nurses.

“Folks,” he wrote, “I could write all night and mention nothing twice, but somehow, I just want to stop it here.

“Love, Jabez.”

Given the chance, I asked what else he remembered from that night.

“Everything,” he said. Pausing in recollection, he added: “It’s humbling to attempt describing the admiration I had for those men – how little we could do in comparison to what they had done.”

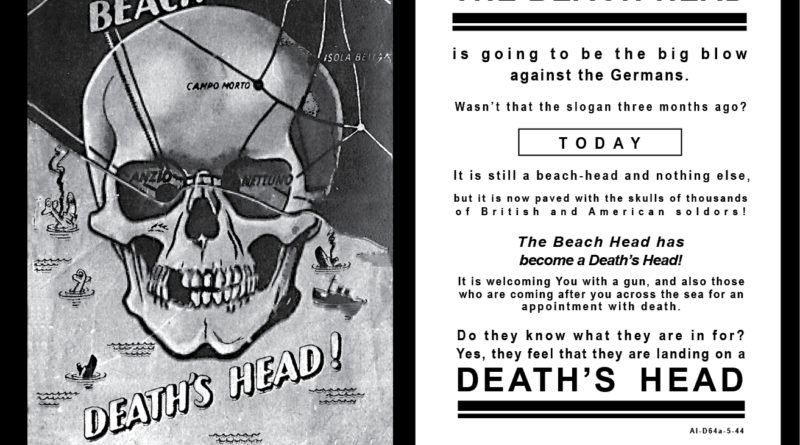

History doesn’t agree with his observation of how little he and his fellow doctors did. In Time Life Books I found the battle on an Italian beachhead near the port town of Anzio that he’d written of in his diary.

The book said this: “The unsung heroes of Anzio were the men and women of the Army Medical Corps who staffed the beachhead hospitals. Because the Allied toe hold was so small, the four evacuation hospitals – no more than tents – were frequently hit by shells. Conditions were so harrowing that one wounded man asked General Lucian Truscott to send him back to the front because, ‘we’re better off there.’”

Dr. Galt wrote this on February 7, 1945, a morning opening the third week of the five-month battle at Anzio: “A plane dive bombed the 95th evacuation hospital adjacent to us with antipersonnel bombs – killed three nurses and a Red Cross girl, one officer and about twenty men. One bomb landed on the Red Cross marker.”

A disjointed scrap of this story includes a meeting between Dr. Galt and Dr. Junsaburo Toyoshima, a Japanese physician during World War II. A member of Rotary International, he was a Mt. Vernon guest as part of Rotary’s exchange program the day Dr. Galt spoke there.

He listened politely for an hour, then stood and asked to address Dr. Galt and the Rotarians.

In heavily accented but unbroken English, Dr. Toyoshima said, “War is the most futile of mankind’s activities. Thank you.”

In April, 1943, Dr. Galt and the 56th Evacuation Hospital with its cadre of officers and nurses from the Baylor School of Medicine arrived at Casablanca. He made light of his first assignment in North Africa.

“We were ordered to arrest soldiers returning from the front for such infractions as having ties askew and failure to salute. This insanity ended when we stopped a jeep with three stars on it demanding to see the driver’s trip ticket. When none was forthcoming, Professor Killis Campbell of the Albany college of surgery apologized but explained that we would need to impound the jeep. One Lieutenant General Ira Eaker asked on whose command. Dr. Campbell replied, ‘by order of major General Arthur Wilson, sir.”

The physicians named the open air cesspool at their camp “Lake Wilson” in recognition of their first war-theater commander. Relieved of duty as cops, the general ordered them out on desert marching exercises.

Tired, dirty and hot, Dr. Galt was resting under a desert palm with Major Andy Small, who was reciting his record of years as a college student, medical student, fellowships and residencies so that he could be a superior surgeon, ‘and that obstinate old mule orders me out here to inhale camel farts.’”

The 56th’s time with camels closed with the launch of the landing on the Italian island of Sicily. The 56th was ordered to the northern brink of Africa to set up a field hospital as close as possible to the Italian peninsula.

They shipped out in boxcars, traveling 1,200 miles across the African continent in two weeks. Disembarking at the foot of the Atlas Mountains, the doctors became truck drivers.

“I drove an 18-wheeler over those mountains,” Dr. Galt said, remembering one lane passes, staring thousands of feet down over the edge. By September, the Allies had pushed onto the Italian peninsula and the 56th went ashore in Italy.

They followed on the heels of the front, serving bloody weeks before the advancing war moved far enough ahead that another evac hospital leapfrogged their position.

“It was odd in that war would be followed by extended periods of leisure,” he said. An explorer, he set out with a camera, traveling the relative safety of Italian countryside like a tourist behind the battle lines.

At Mt. Vernon High he told students of self-appointed medical missions, caring for Italian peasants, poignantly recalling the pleasure of delivering a child and being paid with two eggs.

“Eggs,” he said, “were precious.”

His diary recalled the 56th coming to appear something like a gypsy caravan, “as everyone acquired much furniture and junk.”

In high humor he wrote of doctors commandeering four truck loads of nurses, “creating amazement and cries of ‘Signora! Signora!’ as they crawled up the country. He described “verdant valleys” of orchards, nut trees and vineyards, of stopping trucks in the middle of the road to photograph an old man on a terrace in his vineyard, bowing elegantly and repeatedly as he welcomed American nurses leaping from trucks “in a wild scramble for fresh grapes” while “Major Rippey’s groups ahead remained in perfect decorum.”

He described his first hard look at the aftermath of war.

“Bizerte was just so much crumbled architecture and Avellino was the same but with a core of life to it, a pathetic panorama with frequent close ups of the victims, the old and the young, both innocent but persecuted. As individuals and in groups they dug feebly into the debris trying to retrieve some tangible hold on a lifetime’s work that was atomized. An old lady in a black shawl stood motionless as she gazed at a broken platter dug from ruins. What stories that silent scene held!

“There are too many words,” he said, and stopped writing there that day.

Hearing rumors of the pending Allied invasion of France in early 1944, the 56th was greatly relieved not to be sent there, feeling that their time at war was close to an end.

They were wrong.

Before the invasion of France, the Allies planned a final drive to Rome, sending forces northward up the Italian boot while sending others out to sea to out-flank the enemy and land at Anzio. Dividing the Germans along two battlefronts separated by only a few miles, the plan was the crush them between two armies.

One battle was for Anzio, the next moving inland to the town of Cassino. Full it optimism, it was believed the Allied forces would link up within days. It took five months, a war of attrition carried out during the most bitter winter on record.

At Anzio, one of Dr. Galt’s nurses died at his side. Another became the first woman to receive the silver star for heroism. Time and again at Cassino, British, Poles, French, New Zelanders and American GI’s launched assaults against forces headquartered at a mountaintop Benedictine Monastery dating back to 529 A.D.

Rising 1,700 feet over the battlefield, a mountain that held a Christian shrine lent high ground to Germans who made the most of it. Destroyed in 581 by the Lombards, in 883 by the Saracens, by an earthquake in 1349, each time the monastery was rebuilt on a grander scale. By the time of the Allied assault, its walls were ten feet thick. In the end, it was bombed to rubble.

Ironically, the rubble gave even better cover to the Germans. In one pitched battle, 4,000 Polish soldiers died trying to drive the Germans away.

Each time the remnants of seven American divisions pinned down on the beach at Anzio tried breaking out, they were driven back to the edge of the sea.

From January until May, the two battle fronts raged until finally, worn down by Allied bombs, artillery and relentless infantry attacks, the Germans simply withdrew.

Within days, the Allied armies linked up, driving the Germans back toward Rome and in those days, Dr. Galt walked over the ruins of the monastery.

“I took a photograph there,” he said, “one I didn’t show the students, of a statue of Saint Peter standing chest deep in shattered rock. An inscription in Latin, carved centuries before, read ‘PAX,’ Peace.”

The battle for Anzio began January 22, 1944. The doctors from Baylor followed on January 25th.

The diary reads: “January 25. Sailed. Cold and wet. No food. Very rough. Nearly everyone seasick. Got to Anzio but water too rough to land. Saw two ships burning, one hospital ship and one LST. Heavy casualties. We are apprehensive, sick and filthy.

“January 28. Sailed in through an air raid. Captain Crabtree sailed her in without waiting for orders and told us to ‘get the hell off.’ God this is war! Dog fights in the sky, horrors of burning ships, dying men, bombings, fiery planes. Began digging foxholes seriously and had to use mine before finished.”

“January 29. The ammunition ship Huffington exploded with an earth-shaking roar, throwing flame and smoke thousands of feet up that hung in parallel streamers like a pall. I watched and could have photographed it, but I was too sick at heart – like taking morbid pictures at a funeral multiplied a thousand times. The Luft Waffe with their rocket glider bombs wreaked havoc. This bomb is like a plane itself. One hit seventy steps from my tent, making a hole 50 feet across and 20 feet deep. As we climbed out of the ditch shelter, the BBC broadcast said, “Allied air superiority is such that the Luft Waffe can’t maintain even a reconnaissance plane.”

“January 30. Opened hospital.”

There was not so much battlefield carnage in the fall of the year. There was disease. There were war-numbed minds.

“October 29: The firm of Galt, Rosales, Fortenberry, Johns, Jackson and Collingsworth. Ward 16. Sixty beds, mostly filled. George Reid enters his 14th day of sustained fever, leukopenia, toxic psychosis, negative agglutinations and the most unrevealing physical. Plaxmodium vivax cannot do all of that. And then there is Whisman with acute thyroiditis. A singular disease.

“The battle casualties are light, troops dug in reminiscent of last winter’s debacle. Dug in – what an absurd term. Dug into a small pit of freezing water. Few realize the mental changes that these men are undergoing. They themselves don’t realize it but such degradation and loss of dignity – such humiliation as a man who walks upright and challenges life, now lies cowering in the mud like an animal. These 5th army veterans (if any survive) will be touchy explosives in the future world of armistice – no, I do not say a world of peace existing only in dreams.”

“7th November. I must edit what I have written as it is almost incoherently emotional. Corporal Edmond Viulleumier of 53 Jackson Road, Newton, Massachusetts, died of bulbar polio. I wrote of being at his bedside with him holding my hand and death sitting between us. The corporal could not see death there and I wrote what I hoped, or thought, or maybe he was just man enough to play the game with me as we talked about tomorrow. When he took hold of my hand and held it until he died – sure, I can rationalize and make myself feel pretty good and reassure myself that you can’t do anything with bulbar polio, but here was a man who had called on me for help ad I had nothing but excuses to offer.

“There is Junior, who claims he is 19 but so young there’s not a hair on chest or belly, but he wants to be a rugged soldier and resists any special attention . . . if we might all work together in peace as we have in war, so much might be accomplished.”

When he spoke at the school in Mt Vernon, he said little about the war and more about his slide show, photos of architecture, Italian peasants and soldiers. Beyond descriptions of soldiers celebrating Christmas in his letter home, he didn’t read a word from his diaries.

“May 14, 1945: The war in Europe ended with us in Bologna. Nothing happened then, nothing has happened yet. That day was just a little more quiet, rather solemn. No drinks, no dance, no celebration. I spent day before yesterday in Venice. It’s a grand place. But folks, travel doesn’t hold the old thrill right now. I want to come home.

“Love, Jabez.”

The evening after he spoke at the school and the Rotary club, the townsfolk turned out to sit in folding chairs at the old railroad depot that got its start as a museum with money from Dr. Galt’s orchard. The last of the day’s sunlight streamed in from a low angle, a rich glow of light on raw wood, slowly fading to darkness and night. Against a backdrop of exhibits including a covered wagon, a cotton bale, barbed wire collections and nail kegs, baggage carts and a buckboard, the unfamiliar classics swelled from the instruments of skilled musicians.

Music escaping through open doors drifted over a town for which he longed in a letter written on a hollow day at the end of a war.

With new memories of an older story, Dr. and Mrs. Borders returned to Kentucky.