JFK conspiracy theories rise from mixed blood of Camp, Red River and Titus counties

One time Camp County resident James Tague said the FBI purposely discredited him to discount his first-hand account, testimony that gave life to questions of a second gunman in the assassination.

The man claimed by Barr McClellan to be the second gunman in the Kennedy assassination died in a one-car accident January 7, 1971 on old U.S. 271 three and a half miles south of Pittsburg. He’s buried in Titus County at Nevil’s Chapel.

“Mac Wallace? He died out here?” asked a surprised James Tague, the man whose testimony before the Warren Commission raised questions about the number of shots fired November 22, 1963, when President John F. Kennedy died in Dallas.

By apparent coincidence, Mr. Tague was living near Pittsburg when he was interviewed for the East Texas Journal in March, 2007.

A retired car salesman, he said he’d wanted nothing more than a quiet place in the country when he discovered Camp County.

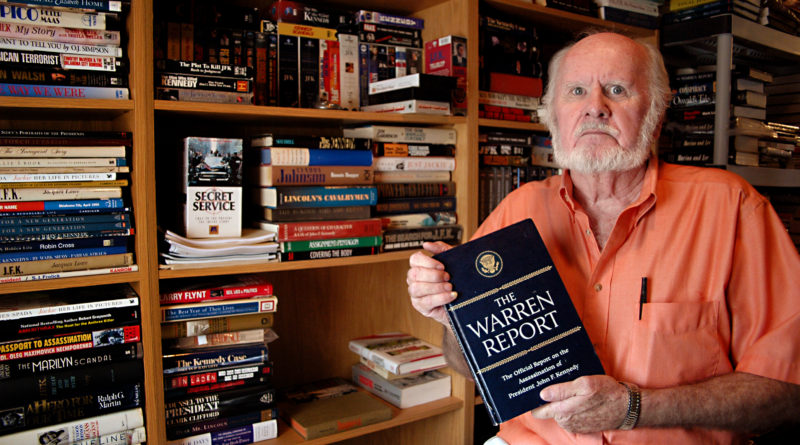

Three shelves of his small library bristled with titles from among some 2,000 books written about the Kennedy assassination.

“There’s so much information, so many theories, so many lists of agencies, individuals and governments who had reason to oppose the Kennedy administration – I think now it’s impossible to know what really happened. Maybe there was a time when we had the truth in our grasp, but it got away from us. Maybe we ran by it,” Mr. Tague said.

During the Warren Commission’s investigation, Mr. Tague testified that he believed he had been struck by concrete fragments from a bullet striking the curb where he stood watching the President’s motorcade.

Records made public for the first time in late October lend credence to Mr. Tague’s recollection ten years ago. He said then that the first references to a conspiracy conflicting with the Warren Commission’s finding of Lee Harvey Oswald as a lone gunman came from within the Federal Bureau of Investigation itself.

His cited his source as Harold Weisberg, a one-time state department analyst whose book “Whitewash: The Report on the Warren Report,” early on questioned the methods and conclusions of the Warren Commission.

The Weisberg account referred to a document stamped secret, a note from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Mr. Tague said.

“The gist of it was that Hoover declared the job of the FBI was to convince America that Oswald was the lone assassin,” Mr. Tague said.

Among the just-released records is a memo from Director Hoover written two days after the assassination and referencing Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach.

“The thing I am concerned about, and so is Mr. Katzenbach, is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin,” said Director Hoover’s memo.

The following day, November 25, 1963, Mr. Katzenbach wrote that “the public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he did not have confederates who are still at large; and that evidence is such that he would have been convicted at trial.”

Among the newly revealed documents is another suggesting links between Lee Harvey Oswald, nightclub owner Jack Ruby and Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit, a native of Red River County.

Less than an hour after the assassination Oswald was arrested and charged with the murder of Officer Tippit, who was shot four times outside a Dallas theater where Oswald was apprehended minutes later. Rising to a bloody crescendo, two days later, as Oswald was being transferred from a police department basement to a county jail, Jack Ruby stepped from a crowd of reporters and shot Oswald.

A misty underworld figure whose business headquartered in a nightclub, America had watched live on television as Jack Ruby killed Oswald with a single shot to the belly.

Born in Red River County in 1924, J.D. Tippit was one of seven children of Edgar Lee and Lizzie Mae Tippit. Theirs was a tight-knit family working rented land, says the website telling his life’s story and committed to his memory. They farmed without tractors, picked cotton without machinery, drew water from a well and cut stove wood with a crosscut saw.

J.D. left school following his sophomore year to commit himself to the family farm, a life interrupted when he volunteered for the service in 1944. A paratrooper, he was awarded a Bronze Star after the 17th Airborne Division jumped into Germany in March, 1945 on a last push to cross the Rhine River in the final days of World War II in Europe.

Returning to Red River County, the day after Christmas of 1946 he married Marie Frances Gasaway, his high school sweetheart.

Seeking their fortune in Dallas, he worked for Sears before returning to farm in the Sulphur River bottom where alternating seasons of drought and flood and the influence of a friend prospering as a Dallas police officer lured the couple back to the city in 1952.

In July of that year he went to work as a $250-a-month Dallas police officer.

Never rising above beat cop in his 11-year career, he moonlighted to make ends meet, worked security. In 1956 he received a “Meritorious Award” following an altercation in which a customer at a west-Dallas nightclub pulled a Saturday night special, a 25-caliber handgun. Reported to have been looking down the barrel of a pistol, Officer Tippit and his partner shot and killed the club patron while making a “routine” club check for drunks.

The website dedicated to his memory describes the opening of his confrontation with Oswald as beginning when he was on patrol diverted by dispatch within minutes of the assassination in Dealey Plaza.

Opening the story of his life, the home page of the Tippit website is up front with criticism of “a cynical world of conspiracy” that in the years since Tippit was gunned down in Dallas has described him as a corrupt officer paid to kill Oswald as part of a convoluted coup plot that failed.

For others, it concludes, J.D. Tippit was an ordinary man immortalized by a line-of-duty chance encounter with the President’s assassin.

Among the 2,800 documents released in October is one from New York offices of the FBI to the agency’s director dated April 1, 1964. An informant identified only by a number is reported to have had a conversation with a second informant claiming knowledge of connections between Oswald, Ruby and J.D. Tippit, saying all were connected to an underground organization called “Fair Play for Cuba.”

During Kennedy’s administration, the President was believed by many to have been accountable for withholding resources related to a CIA mission to overthrow Cuban strongman Fidel Castro. A covert operation broke into mainstream media at the Bay of Pigs, where Castro’s troops defeated a unit intent on the overthrowing the island nation’s communist regime. Oswald, he said, was playing both sides of the street, proclaiming allegiance to both those supporting and opposing Castro.

In the wake of Dallas, J.D. Tippit was revered as a tragic hero whose murder left behind a widowed mother of three. Before the end of the day he died, Mrs. Tippit received calls of condolence from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the late President’s brother, and Lyndon B. Johnson, the Vice President who’d become the new President.

Moved by the family’s plight, contributions poured in from across the nation. One of the largest was from Dallas businessman Abraham Zapruder, $25,000 he’d received from Life Magazine for a home movie that had captured the assassination.

In January, 1964, J.D. Tippit was posthumously awarded a Medal of Valor from the American Police Hall of Fame, the Police Medal of Honor, the Police Cross and the Citizens Traffic Commission Award of Heroism. A Texas Historical Marker was erected on U.S. 37 southwest of Clarksville, near the site of his family’s home in Red River County.

A second memorial was unveiled in November, 2012, at the site where he was killed.

In 2003, the 40th anniversary of the assassination, James Tague broke into the ranks of recorded conspiracy theorists with his first book, “Truth Withheld.”

A young car salesman working at Chuck Hutton Dodge on Lemmon Avenue, Mr. Tague was thrust into the most studied and theorized assassination in history because he got held up in traffic on his way to a lunch date.

“I was heading into town to meet a cute redhead,” he said.

As he approached Dealey Plaza and the Texas School Book Depository where Oswald worked, he hit gridlock traffic coming to a stop beneath a triple overpass by the “grassy knoll.” Many not persuaded by the Warren Commission that Oswald acted alone believe there was a second gunman on the grassy knoll.

Exiting his car, Mr. Tague had just walked from beneath the overpass when the first shot was fired.

He said it sounded like a cannon went off. He felt a sting on his cheek. He ducked behind a bridge abutment. Gunfire echoed. People screamed. The motorcade sped away.

He saw a motorcycle cop stop, draw his gun and run up the grassy knoll. He moved toward the activity until he ran into the officer he identified as Clyde Haygood when he was returning to his motorcycle. Within earshot, a witness running to Officer Haygood reported seeing shots fired by a gunman from a high window in the Texas School Book Depository across the street.

Other accounts placing Mr. Tague at the scene say that he was first approached by Dallas County Sheriff’s Office detective Buddy Walthers.

Mr. Tague said he listened as Officer Haygood radioed dispatch and asked that the depository be sealed off. Noting blood on Mr. Tague’s cheek, he reported a bystander with a superficial wound.

In short order, Mr. Tague said he was at police headquarters giving his statement to a homicide detective named Gus Rose.

“It was bedlam,” he said. “About 15 minutes after I got there, two cops came in with a handcuffed suspect who had just killed a police officer. I turned and looked as he passed.”

The following day, Mr. Tague said he recognized Lee Harvey Oswald from news accounts as the man the officers had brought in.

“Naturally, I was watching the newspapers,” he said. Any number of accounts describing damage to the curb where Mr. Tague stood led him to conclude he was hit by a concrete shard when a shot hit a segment of curve later sawed out and enshrined as a museum piece. Whether or not it was damaged by a bullet remains to this day a key point of debate.

Nearly seven months later, Mr. Tague said he contacted a newspaper reporter after reading an account of the Warren Commission wrapping up its investigation and concluding that three shots had been fired. The first struck the President. The second struck Texas Governor John Conally, who was riding beside him. A third struck the President again.

Curious about which shot then might have hit the curb, Mr. Tague described a June 5, 1964 meeting with Jim Leherer, who was then a reporter with the “Dallas Times Herald.” He said they also discussed an 8-millimeter film he’d made at the Indy 500 where drivers Eddie Sachs and Dave McDonald had died in a fiery crash the weekend before.

He brought the film to the dealership, he said, to show it to the sales crew and he wondered when he spoke with Leherer whether the film was of any value.

Following their morning conversation, he said Leherer called back in the afternoon eager to write a story for the newspaper’s evening edition.

“I said it was okay with me as long as he didn’t use my name,” Mr. Tague said.

In conspiracy theory accounts, the question swirling around Mr. Tague’s story has always been the question of a fourth shot lending credence to second-gunman questions. In the Warren Commission summary account, the question turned more on Mr. Tague’s nature and his motivation for talking to a reporter.

“Within an hour of the time Jim Leherer interviewed me, the story was out and within another hour he’d called me back to advise me he’d been contacted by an investigator with the Warren Commission demanding to know who I was,” Mr. Tague said.

He was subpoenaed and testified in July, 1964.

The commission’s summary of the testimony of Jim Leherer has a different twist, reporting that Mr. Tague approached the reporter wanting to sell his story.

Mr. Tague wrote about that in his second book, “LBJ and the Kennedy Killing.” Published in 2013, six years after he’d been surprised to find that Titus County native Malcolm Wallace had died in a crash in Camp County, that book focuses on connections between Lyndon Johnson and Malcolm Wallace.

In the second book, Mr. Tague took issue with the way he was characterized by the Warren Commission.

“One of the things in that FBI report that aggravated me was about my asking Mr. Leherer if the film of Indy crash I had showed him had any value,” he wrote, “and now the FBI was saying I was trying to make money off the assassination of President Kennedy. People in the know have told me that is the way the FBI writes their reports when they want to discredit you.”

Google James Tague and you’ll get about 369,000 results.

Google Malcolm Wallace and you’ll find just short of 18 million.

In “Blood, Money and Power” writer Barr McClellan says Wallace was a henchman for Lyndon Johnson. It says Johnson, an Austin lawyer named Edward Clark and Malcolm Wallace were involved in the assassination and a cover up that followed. Mr. McClellan worked in Mr. Clark’s law firm.

Allegations of Wallace’s connections to the assassination were aired again in a 1998 edition of “Fair Play,” an on-line magazine. An article by John Kelin said a previously unidentified fingerprint found on a box in the “sniper’s nest” on the 6th floor of the School Book Depository belonged to Wallace.

A former Marine and a one-time University of Texas Student Body President, Malcolm Wallace met Lyndon Johnson after going to work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in October of 1950.

The tale submerges into McClellan’s writing of a relationship between LBJ’s sister and John Kisner, a 33-year-old University of Texas student who was shot and killed at the Pitch and Putt Golf Course near Austin on October 22, 1951. McClellan said Kisner had asked Johnson’s sister for a loan and that then-Senator Johnson interrupted the request as a threat, believing his sister had told Kisner tales of politically corrupt dealings.

At trial, Wallace was defended by John Cofer, who had defended Senator Johnson when he was accused of ballot rigging in a 1948 Senate Race.

Obituaries in the Dallas Times Herald said that after living for some years in California, Mr. Wallace had recently returned to Texas where he died in the one car accident near Pittsburg on a winter’s night.

Mr. McClellan wrote that Wallace died after his exhaust was rigged to flow back into the car while he was in a meeting at a Longview oil company on January 7, 1971.

Oil had come into play as the payoff for the Kennedy assassination, money flowing from tax advantages for oil producers during the Johnson administration, Mr. McClellan wrote.

Mr. Tague moved from Camp County. He died in Bonham in 2014 at the age of 77.