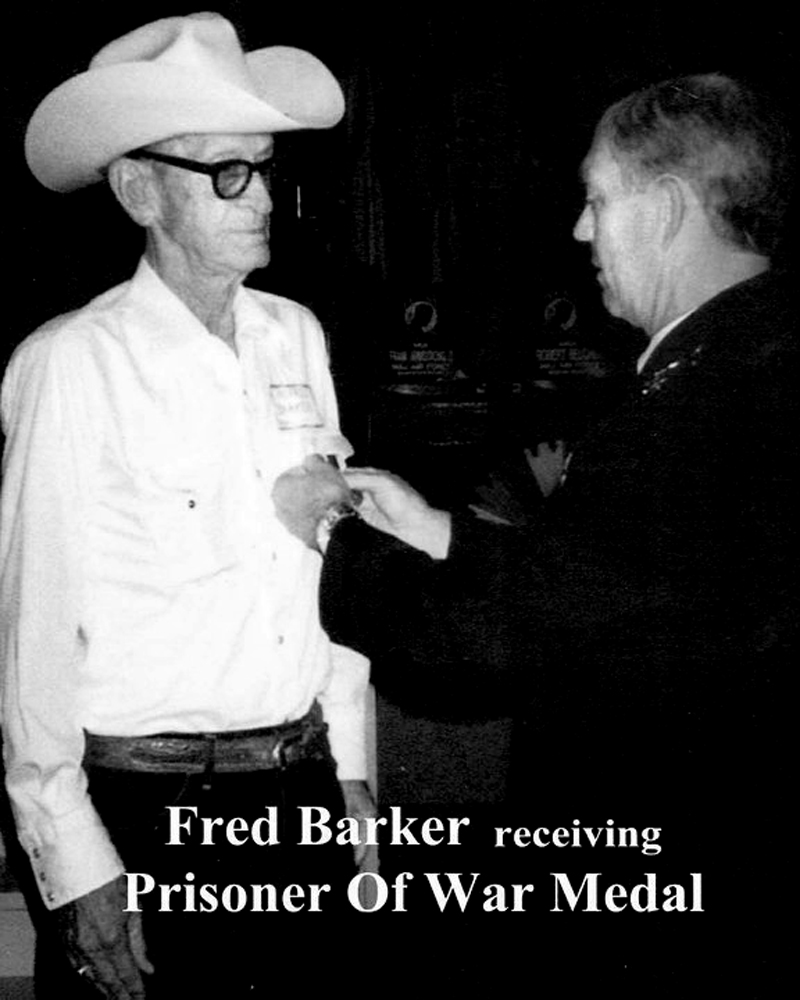

Cattleman recalled German POW camp

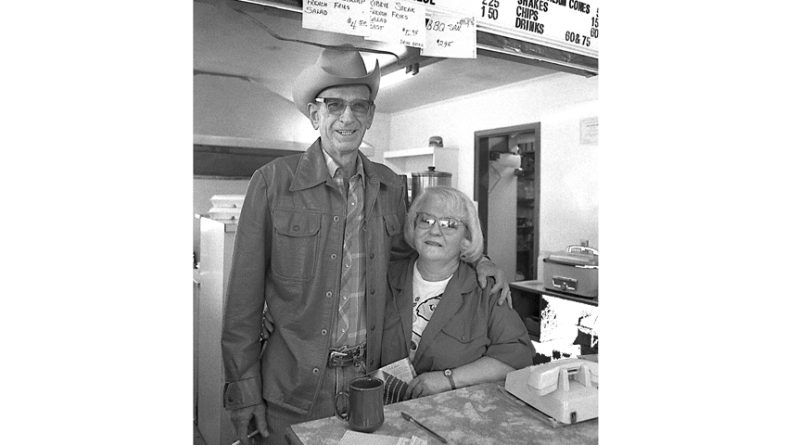

Above photo, Cattleman Fred Barker set up his morning headquarters at Linda Stinson’s Dairy Bar in Mt. Vernon.

From East Texas Journal, December 1993

By Hudson Old, Journal publisher

MT. VERNON – Ladling chicken gravy onto his mashed potatoes on a Sunday noon, Fred Barker recalled bits and pieces of his brief career as a fighting infantryman in World War II.

As history works out, a pair of Franklin County men played bit parts in what turned out to be the final months of World War II in Europe.

A week to the day before Germany began its final offensive, Fred Barker and Velvin Bolin found themselves crawling on their bellies through the snow in the final hours before dawn on a Sunday.

It was to be their first and final day of combat.

“Starting with basic training at Mineral Wells, we went through together, all the way,”Mr.. Barker said.

By the winter of ’44, when they landed in France, the Allies had pushed the Germans out of France, back through most of Belgium, advancing the front to the Ardennes Forest on Germany’s western border.

As new recruits, they went straight to the front lines, winding up at a place he recalls as “Camp Lucky Strike.”

“It was a city of tents,” he said. “There was one building as long as from here to the highway, full of nothing but duffel bags and they had us to throw ours in with the rest.”

He might have gotten a clue of what was coming when he asked another enlisted man how they’d ever find their duffel bags when they came back — he was told they wouldn’t be coming back.

” I never believed that for a minute,” he said. “Somebody asked when I did get back if I’d been brain washed while I was a prisoner — I told ’em I was brain washed before I ever got to the front. In basic training, any time they told us to take something, we took it.

“There were 18 of us sent out that Sunday morning — they told us to push the Germans back across this little river and then they’d sent in reinforcements and bring us back for R & R. As far as I was concerned, we were going to go win a fight, then come back and have a big time.”

At daybreak, with three tanks behind them, the 18 men moved out in the snow, began firing on a German machine gun nest.

Almost immediately, their radio man’s radio was shot off his back. The tanks broke off the engagement and retreated.

“That first machine gun nest was about 150 yards into the forest,” he said. “Whenever the tanks went back, we had a Sergeant who started arguing with our lieutenant wanting to turn back. The lieutenant ordered us on into the woods.”

A grenade through the opening of the first log machine gun nest took it out. He remembers laying by the nest with Mr. Bolin while the Germans showered them with withering fire. The sergeant continued to argue with the lieutenant.

Before they reached the second machine gun nest, all 18 men were pinned down by cross fire. By that time, the Germans had circled around behind them, cutting off their escape. Now the sergeant was urging the lieutenant to surrender. A grenade landed among them — the sergeant kicked it down the hill before it detonated. He wasn’t so lucky the second time.

“That next grenade took off his foot,” Mr. Barker said. “Then he ran up a white flag, and that was it. We were prisoners.”

Their captors were somewhat irregular — soldiers comprised of men and women.

The Americans again began advancing their tanks — his first act as a POW was to flee with the Germans back to the safety of their trenches. They left the lieutenant behind until one of the 18 asked permission to go back and get him.

Carrying their lieutenant on a stretcher, they began marching toward Germany’s heartland around mid afternoon. They marched through the night until they reached a hospital the next morning, a hospital built in the side of a mountain.

They were ordered to leave the lieutenant there — Mr. Barker asked him his name and where he was from. It was the last they ever saw of the lieutenant.

It was a Monday morning, December 10, 1944. Without rest, the prisoners were marched all day until they reached the city of Bonn. That night, the Germans brought them cheese — it was the last food they were to receive for days.

Eventually, they were loaded in box cars for an agonizing three day trip across Germany. “We were packed in tight enough that there wasn’t room for everybody to lay down,” he said. “We slept as best we could in shifts.” During those days, they ate the last of their cheese and got water from the frost inside the box car. Their hands and feet froze.

In the months that followed, they were moved from camp to camp, deeper into Germany, sometimes aboard trains, sometimes they marched.

“Other than being always cold, wet and hungry, we weren’t mistreated,” he said. In the different towns where they were held, the SS troopers who guarded them were always calling for “volunteers.”

“You learned to volunteer in a hurry,” he said, “because working meant food.” They were fed a pint of “some kind of grass soup” and an eighth of a loaf of black bread a day.

They could report to “sick call.” “They’d take you to a little infirmary and you’d sit outside in the snow all day waiting for medical attention. I got sick enough once to go — but I just sat outside all day and the doctor never came. The next day, I decided that sick or not, I wanted to work because I wanted to eat,” he said.

That day, an allied bomb hit the infirmary. Everybody inside was killed.

“It was to your advantage to be from the country,” he said. “We knew a little about how to get by. Once when a mule was killed, we got to eat the mule.”

Mostly, the prisoners were used as slave labor to make railroad repairs after Allied bombing strikes.

“We filled in holes the size of houses using wheel barrows and shovels,” he said.

To the credit of his nature, Mr. Barker didn’t recall much about being abused by his captors — there was a single incident when he was hit with the butt of a rifle for singing. As the prisoners were shuffled from city to city, he found that even the citizens of Germany were slowly starving. And he remembers their acts of charity toward the POWs.

There was one guard who spent his nights mining for food in the bombed out craters of German homes — “All the houses had cellars where they stored potatoes. This guard would put potatoes between the ties in the track and allow each prisoner to get a single potato.”

In one town, each day as the prisoners were marched seven miles to work, they passed the home of a woman who left her hog’s slop hanging on the fence.

“When it dawned on her that we were stealing her slop because we were starving, she started washing her slop bucket every day. And she’d peel her potatoes so that the peels were a quarter inch thick.”

In April, some 1,200 POWs were being marched to yet another camp.

“There was always the promise that at the next camp, we’d get Red Cross packages,” he said.

The men were hardened by then, if not physically, then mentally.

“Some men just went over the edge,” he said. “We’d all seen them carried away, and once they were carried away, they never came back.”

It was Friday, April, 13 when they met up with a group of Russian POWs.

” I remember this Russian telling us to listen — then we could hear the sound of small arms fire in the distance and we knew, or at least hoped that the end was near,” he said.

The back third of the column of 1,200 men came up with a plan.

“Most of the guards were up in front,” he said, “so the word started coming back down the line that we were going to lag back and then attack our guards. They only had side arms.”

As the main group of prisoners went out of sight over a hill, the 400 turned on their guards — the fight never came.

“It was simple at the moment,” Mr. Barker remembered. “They could have killed some of us, but they could never have killed all of us before we killed them.” Their guards wisely surrendered.

They took refuge in the homes of German citizens, and that day they watched as the German army beat a retreat through the town.

“Anybody in that town could have tipped off the Germans,” Mr. Barker said, but none did.

On their first night of freedom, the Americans slept in the homes of German citizens.

Sun streamed in there on the porch, shining on the piles of Sunday fried left over chicken. The talking had ended. There was more fresh broccoli, a quart of gravy left, and still a mountain of whipped and seasoned potatoes. Nancy began clearing the table, putting up the leftovers.

Mr. Barker was reminded of the day he and Mr. Bolin stole potatoes from a mule drawn wagon back in Germany.

Daughter Nancy, Mr. Barker’s oldest, came out of the kitchen with a steaming cobbler, served it up in bowls with big scoops of ice cream.

It reminded him that once the POWs got around food, they couldn’t eat much.

“Our stomachs were drawn up to the size of hickory nuts,” he said, tasting the cobbler. “

I asked if, after being freed, the Americans were well behaved in Germany. Mr. Barker conceded that he and Mr. Bolin stole two bottles of liquor.

“We traded them for food,” he said.