Gooch Springs treasure unearthed

From East Texas Journal, July 1992

A SILVER PIECE of eight was the first link amateur archeologist and Baptist minister Bill Anderson was able to make between an ancient Titus County trading post and the Spanish trading fleets that ruled the seas as Europe slipped from the middle ages into the renaissance.

Common currency in Spain’s global trade, the coin turned up among the pottery shards, flint tools and French trading goods Anderson has unearthed in the past 15 years at Gooch Springs.

He discovered the site some 20 years ago when state archeological teams were called in to survey land along Swauano Creek that today is the murky floor of Lake Welsh.

“I found my first arrow head when I was nine,” Anderson said. explaining His life time interest in archeology. “When the state opened that country around Lake Welsh up to their archeologists, I just invited myself along.”

State archeological teams—the guys we pay–determined that the Gooch Springs archeological site would soon be covered by the lake.

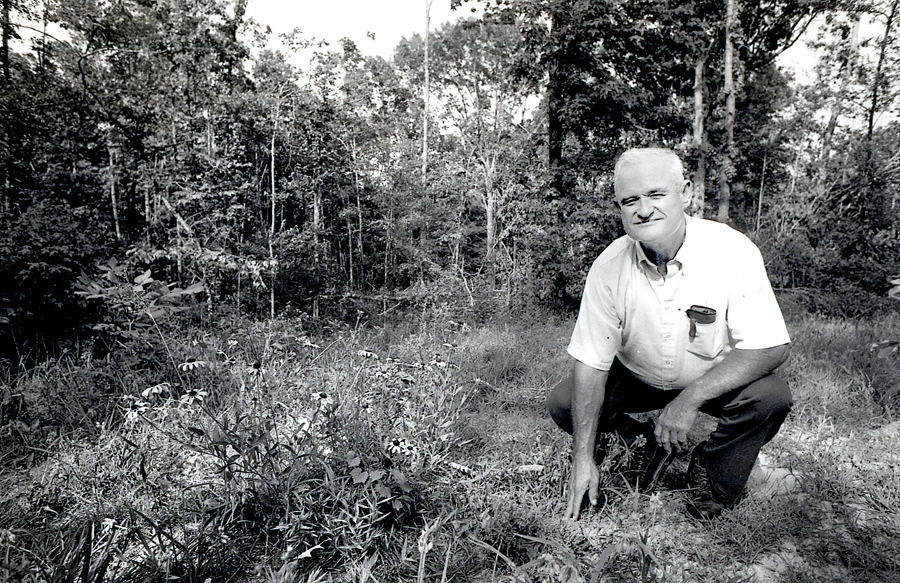

But Anderson, poking around in woods further up stream, found his archeological paradise.

“It was one of the richest sites I’d ever seen,” Anderson said. “The area was heavily wooded and thick with undergrowth, but all you had to do was look close–there were pottery shards and signs of flint work everywhere.”

The yearning to work the site ran so deep that Anderson, a state highway department employee, dreamed of buying the land. And he got it done.

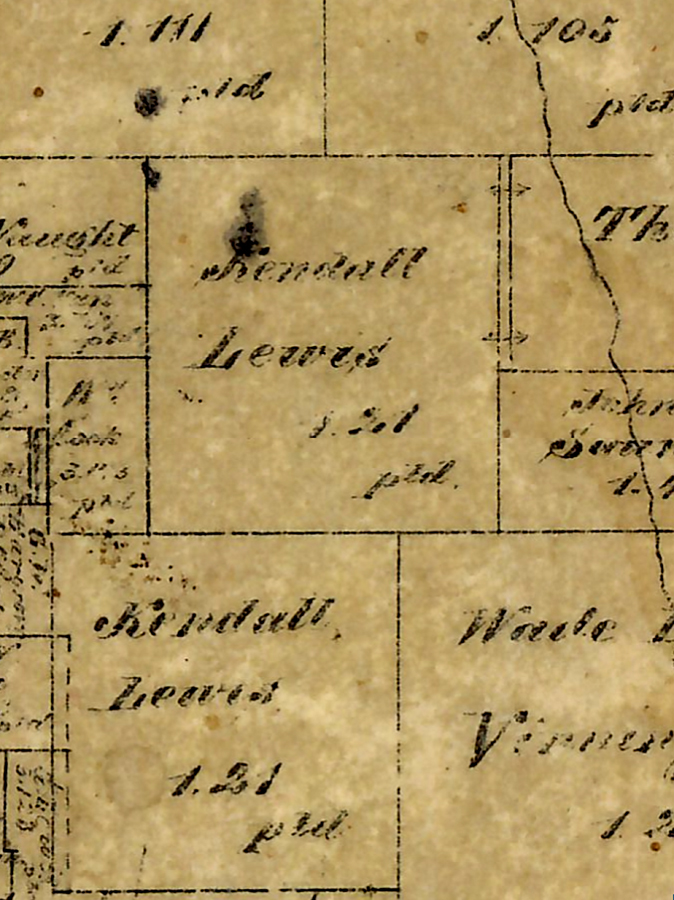

The 17-acre tract lies on either side of two abstracts in the Kendall Lewis survey, one of the earliest surveys patented here by the Republic of Texas.

There are two Kendall Lewis plats—the earliest available Titus County records reflects the patent signed by Republic President Sam Houston of only one of the surveys. The other patent could have–and likely was--filed in Red River County. Or, the original file could have been destroyed in the Titus County Courthouse fire of 1895.

Anderson’s 17-acre tract lies across both surveys. The dividing line, be maintains, was once used by the five Hassina speaking Indian Tribes inhabiting the Southeastern United States known as the Confederation Trace, the meandering route that led through Caddo and Choctaw Indian nations. The Caddo were the predominant tribe in North East Texas

Kendall Lewis was a native of Georgia. Anderson suspects that Lewis first came into the lands of the Louisiana Purchase sometime after the United States bought the land from France in 1803.

At any rate, state archeologist have determined that Lewis came into East Texas through Caddo Lake, and, for a while in the 1820’s lived on there.

By 1830, they conclude, Lewis bad moved to Swauano Creek in Titus County.

“His home,” the report states, “became a trade center and inn for Indians and traders along the trail.”

But Anderson’s conclusions have strayed from the state report on several points since he began his dig.

Anderson knew by looking some 20 years ago that the site bore historical information of both white and Indian history.

The pottery shards and flint he first noticed were in the shade of a Walnut grove. Settlers from the eastern states were the first to bring Walnut trees into the country.

And while be suspected that he could well be excavating the old Kendall Lewis homesite and trading post, he couldn’t nail the fact down until he discovered the cache of polished bone flute keys, each with the tiny initials “KL” carved in them.

At that point, the shadowy history of Kendall Lewis began taking personality—-either the man or his Choctaw wife played the flute.

Other evidence would indicate that there was a lively trade at the site, a trade that was literally international. Among the hundreds of artifacts already cataloged are French trading beads, European trade pipes and copper fashioned into a ceremonial Indian headdress.

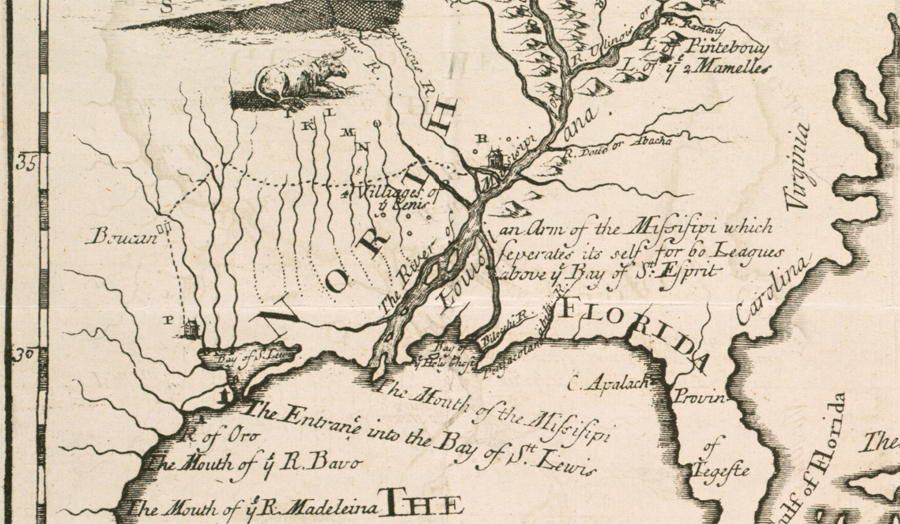

There is agreement among archeological scholars that the earliest recognized European exploration of the area came with DeSoto’s expedition from 1539 to 1543.

Latter, LaSalle would be credited with coming up the old Indian trail between 1685 and 1687.

The French axe Anderson has unearthed at Gooch Springs could have been left behind by Ponce de Leon, whose forray into the area is dated 1689.

Traditional maps showing explorer’s routes scrape by Anderson’s site without actually touching it—LaSalle is said to have gone through present day Morris County, a few miles south– others were thought to have traveled along the next creek to the south and west, the Cypress.

But, for most of us, who sometimes have trouble recalling where we left a screwdriver the last time we used it, what is the probability of irrefutable proof of the location of a five-century old Indian trading route?

“The trade goods found at the Kendall Lewis site leave no doubt in my mind that the site sits exactly on the established route,” Anderson said. But the most compelling evidence, a scrap of the rarest of treasures from a Spanish trading vessel, will virtually seal that conclusion, barring the investigation taking some unexpected turn.

As early as the 1570s —and possibly before — the Spanish fleet rounded the tip of South America and established Manilla in the Western Hemisphere as its gathering point for trade with China and the Indies.

”To get hack to Europe, they sailed to the western coast of the Americas and carried goods overland to ships on the west coast of the Gulf of Mexico at Vera Cruz,” Anderson said. “From there, ships sailed through the gulf to the Atlantic and on back to Europe.

“Between 1500 and 1700 the Spanish lost some 200 ships at sea, many of them in the Gulf of Mexico,” Anderson said.

A few of the shipwrecks occurred in the vicinity of Cuba, which was handy for survivors since Cuba was a thriving Spanish port.

Others, though, occurred all along the coast of the Americas. Getting back to Spanish civilization then meant either getting back to Cuba by boat, or, lacking that, the overland trip along the old Indian trading routes leading to the El Camino Real the Spanish road connecting Mexico City with North America.

Anderson believes it was one of those ill-fated Spanish sailors who somehow left behind the moonstone that be unearthed at the Kendall Lewis site.

“I believe this was a trading site long before Kendall Lewis arrived,” Anderson said. That fits in with his finds.

Immediately beneath the layer of the world where he found Kendall Lewis, Anderson has uncovered extensive evidence of the Caddos, dated loosely as the “Historic Period.” That’s from Columbus forward.

A little further down he’s unearthed Native American relics from the neo-American period, whose dawning is generally paralleled with the time of Christ.

Lower still, Anderson has found Clovis points, those reaching back into times unknown, when man first began making stone tools.

Ten years ago, sifting through the site, Anderson found what might first appear to be an oddly rounded piece of quartz.

Stay with incidental information here.

Years before, Anderson’s interest in gems was developed beginning when his mother showed him a plate illustration from the family encyclopedia. There, amid row of rank and file photos of gems, was a ”Moonstone,” rare, found only on the East Indies island of Ceylon, and believed as far back as the middle ages to have curative powers.

“I knew what it was the minute I saw it,” Anderson said. ‘I’ve spent 10 years now proving it”

In the pages of National Geographic Anderson found a story of the riches lost in the wreck of the Spanish treasure ships off the coast of Florida. Among the listed items of cargo — with an illustration – Anderson found a gold cross, each of it points encrusted with a gem and the Moonstone he believes he’s found at its center.

The size and shape of the stone fit into the puzzle of its treasure status.

The Morgan-Tiffany Collection of gems displayed at the Museum of Natural History boasts of an 11-carat Moonstone. The smooth stone Anderson discovered is something over 100 carats.

“Even before I found the National Geographic article, the only way it remotely made sense for this stone to be where it was was that it came from a Spanish ship,” Anderson said. “I knew then that the Spanish traded with the Chinese, who traded to the Indies. Everybody who knows gems knows this particular stone had to come from there.

“Since discovering that this particular cross with the Moonstone in the middle went down in a ship wreck, the only plausible explanation is that it was — for whatever reason —left behind by one of those Spanish sailors,”Anderson said. “No doubt he survived the wreck and was traveling the Indian trails back to one of the Spanish ports.”

Logically, the idea of the stone’s being part of a Spanish treasure ship would dove-tail with the find of the Spanish coin at the same place.

Though its treasure status piques the imagination, the discovery of the Moonstone only brings into focus a moment in time, at a location steeped in history.

Written history reveals that because he was married to an Indian woman, Kendall Lewis was forceably removed from Titus County, herded into the Indian territory in 1842. So far as Anderson knows, nothing was ever heard of Lewis afterwards.

Anderson further believes that a part of his personal family history floated through Gooch Springs in the river we call time.

Anderson’s great grandfather, J.B. Parrack, wrote a book called One Heart That Never Ached, the story of his mission to the Indians.

His missionary exploits are intertwined with his search for a missing heir. Parrack tells of being commissioned to locate one Joan Allgaits, beginning in Chicago and following her trail for 10 years — he tells of his travels along the Choctaw trail.

Whether it actually happened or not we’ll never know, but Anderson believes it likely that Parrack would have stopped to preach at Gooch Springs.

“That was simply a focal point, a gathering place for people,” Anderson said.

Anderson says he won’t live long enough to complete the excavation of the Kendall Lewis site.

“As long as I’ve been at it, I’m maybe 30 percent of the way completed with that one site,” he said “and I’ve identified three other sites on the same tract of land.”

Ironically, for one who has unearthed such a wealth of history, Anderson’s work is scarcely recognized by the scholastic archeological world.

He communicates with state archeological teams by letter, telling them of his finds, and they do, from time to time come to copy his catalog and file information, no doubt using his work to weave into the fabric of larger studies.