One-time lawman made last-ditchattempt to escape electric chair

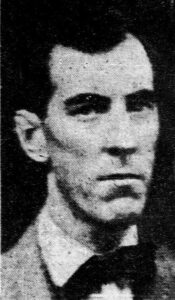

Within a month of the September 24, 1923 murder of Ottis Ballard, one-time Titus County Sunday school teacher and lawman G.C. “Clem” Gray was arrested, tried and sentenced to death.

Just under two years later, the watch on death row at Huntsville discovered Gray had slit his own throat with a straight razor at the end of the surreal night of his execution.

“Warden T.J. Howard went into the death cell with a club and subdued Gray. Protesting his innocence and bleeding profusely, the condemned man was dragged to the death chair,” read the evening edition of the August 7, 1925 Mt. Pleasant Daily Times.

Yellowed and brittle, the pages of records in the Titus County District Clerk’s office detail bizarre accounts of violence justifying the defendant’s being brought to court in chains. That was the first of 25 points of appeal filed two days after his October 19 conviction and death sentence for the murder of one of three young accomplices in the burglary of an Upshur County Bank at Rosewood.

In the drama played out during the summer and early fall of 1923, Ballard was killed nine days before he was to have testified against Gray at his October 3 Upshur County trial for the bank heist. Even without Ballard’s testimony, Gray was convicted and sentenced to ten years. Within days, he was arrested again, taken into custody by Texas Rangers and turned over to Titus County where he was charged with killing Ballard.

Dr. W.T. Ballard, father of the slain man, testified that four days after the burglary of the bank Gray had come to his home asking that his son flee the country until “Gray could come clear in Upshur County.”

Already facing prison time in an unrelated crime, the trial transcript includes Ottis Ballard’s subsequently sending word by Gray’s hired man Burl Kemp for Gray to meet him in Jefferson. There, Gray testified, they discussed his funding $300 for Gray’s three accomplices in the bank job to flee to Old Mexico or South America before his Upshur County trial.

On the Saturday before Ballard’s Monday night murder, two others accused in the burglary, George McKinley and Paul Keith joined in a conspiracy. They both agreed to flee the country, earning their get-away money by “getting Ballard out where Gray could talk to him.”

Days before being convicted and sentenced to 30 years as an accomplice in Ballard’s murder, Burl Kemp turned on his boss and testified on behalf of the state at Gray’s trial.

Kemp said he wasn’t present when Ballard was bludgeoned, but that he had provided two pieces of pipe Gray requested – the iron bar that was the murder weapon and another that was used to weigh the body down when it was thrown from the bridge over Cypress Creek on “the Jefferson Road.”

Another lured into the plan, Nig Gamble, testified that Ballard was among a group of boys he’d driven to Mt. Pleasant’s East Side School grounds where there was a jug of whiskey waiting. He testified that the boys were singing when Gray and Kemp arrived.

Whether Kemp followed when Gray and Ballard disappeared along a forested trail leading from the edge of the school grounds was a matter of dispute. Kemp said he wasn’t there – Gray testified that it was Kemp who followed them into the woods with murder on his mind.

“No!” Gray claimed he cried as Kemp attacked Ballard.

Whoever fingered him – and there were plenty at the trial – Kemp was taken into custody the following day.

It was later reported the “truth serum” was given to “a number of Negroes at the Titus County Jail by Dr. House of Venus,” prior to Gray’s arrest. “Confessions were obtained,” read the Mt. Pleasant Daily Times account of the trial.

Both Kemp and Gray gave confessions, but each accused the other of the killing. Gray testified that he agreed to help dispose of Ballard’s body fearing that he would be suspect if the murder came to light. Ballard’s anticipated testimony in the upcoming Upshur County trial provided clear motive.

Sheriff W.L. Kelley testified that Kemp described both men becoming covered in blood as they dragged and loaded Ballard into Gray’s open roadster. Securing a weight about his neck with barbed wire, they stripped the body before dumping Ballard in the creek. Back at Gray’s residence, they shucked their bloody clothes. Kemp said he burned everything later than night on the right of way of the Paris and Mt. Pleasant railroad. Burned buttons were found on the rail right of way.

The sheriff said it was Kemp who told them where they’d find Ballard’s body four days after the murder.

Over the next year, a cadre of attorneys represented Gray. Prosecutors at his Titus County trial were District Attorney T.C. Hutchings, County Attorney Sam Williams, State’s Attorney Tom Garrard and Assistant State’s Attorney Grover C. Morris.

Gray was originally defended by Florence and McCelland and Meyers and Meyers, all of Mt. Pleasant. Dallas attorneys Callaway, Short and Callaway and M.T. Lively handled his appeal.

One of the points of appeal was his father’s testimony that he recognized the bloated body of his son only by the color of his hair.

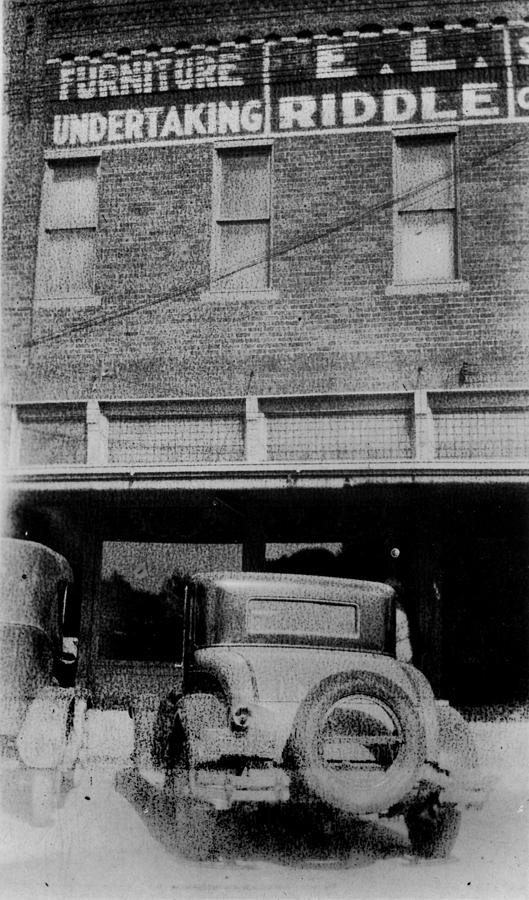

When Ballard’s body was recovered, news accounts describe a crowd descending on the mortuary at Riddle Furniture Company, a mob that turned vengeful when Gray was arrested. Despite Dr. Ballard’s plea to let justice run its course for his son’s accused killer, he was spirited out of the county for fear of lynching.

In the days that followed, Sheriff Kelley testified, Gray responded violently as he was moved from jail to jail, nightly rotated between cells in New Boston, Paris and Tyler. On the first occasion that he was handcuffed for transport, he called for the eternal damnation of the three deputies required to subdue him.

He wildly demanded that the sheriff fight him like a man, then begged to be killed. Cuffed while being driven between New Boston and Paris, he’d sprung on the driver, strangling him before being restrained.

With that testimony supporting the sheriff’s request that Gray be brought into court in chains, security during the trial included three Texas Rangers, five deputies, “several constables, the city Marshall and various officers from other towns.”

On appeal, his attorneys argued that Gray had been purposely made to appear to be a dangerous man before the jury.

Convicted and sentenced to death on October 19, 1923, Gray was transferred to the Dallas County jail while his case was on appeal. While he was there, he rose on a tide of celebrity riding a media-fueled barrage of sensational news accounts.

Described as a model prisoner who had the run of six floors of the Dallas County jail, one account reported his being “convicted by a prejudiced jury at a mob trial on the testimony of a Negro.”

The “man of iron” exhibited “nerve never failing and he has never quit smiling,” reported The Dallas Dispatch.

Dallas Sheriff Dan Harston went to Austin to plead personally before the governor on Gray’s behalf after a court of appeals in Austin upheld his conviction and death sentence June 18, 1924.

The Dispatch reported members of the Dallas legal community soliciting Austin and said a personal friend of the chairman of the state’s board of pardons and paroles appealed to him for Gray.

Cora Seeman, “a wealthy woman” and sister-in-law of the condemned man asked for pastors to hold prayer services and telegrams poured into the office of Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson imploring her to commute Gray’s sentence.

It was universally reported that the only protests against commuting Gray’s sentence came from Mt. Pleasant and Titus County.

“While Titus County was wide open and overrun with bootleggers, the tall, smiling Sunday School teacher put aside his Bible and punched forth into the whiskey business,” the Dispatch reported, probing into Gray’s past.

Clem Gray had been a Titus County lawman and later, an agent of prohibition before he switched sides.

His whiskey running caught the attention of the legendary Texas Ranger, M.T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas.

The lore found in the “History of the Texas Rangers” includes a chapter about Gonzaullas battling against Texas bootleggers during prohibition. In the early 20’s he caught Gray in Dallas with a load of Titus County moonshine.

Gonzaullas was one of the Rangers who’d closed in to arrest Gray for Ballard’s murder, then guarded him as he sat in chains through the days of the trial.

Back in Titus County, years before Ballard’s murder, there had been whispers of Gray’s supporting a mistress in Dallas. At his trial, his wife testified that he had anguished over financial troubles in recent years.

The trial records include a copy of the death warrant delivered to the Titus County Sheriff June 30th, 1925. His date of execution was set as “before sunrise, August 7, 1925.”

He was transferred from Dallas to Huntsville’s death row.

The day before the execution, the Dallas Morning News tracked the victim’s father, Dr. Ballard, to the governor’s office. The paper reported Ballard’s account of intervening for Gray when a Titus County mob wanted him handed over for hanging.

“I’ve now asked the governor to allow the court’s sentence to stand,” he told the Morning News.

The Morning News reported that the fathers of the victim and the accused passed in the capitol hallway.

With the press hounding his steps in the final hours before his son’s execution, Clem Gray’s father finally spoke.

“Clem was highly respected in our community until he mixed up with whiskey,” R.J. Gray told the Morning News. “That has brought about his downfall. I came to see the governor and ask that she save my boy. If she spares his life, I will be proud, but if she decides otherwise, it cannot be helped.”

The governor refused to see Minnie Gray, Clem’s wife, saying she had to prepare for a ball being given in her honor that evening, the Associated Press (AP) reported, based on an interview with Gray’s oldest son.

Gray’s wife, attorney and two sons “completed a lengthy conference with Governor Ferguson’s husband, the former governor, just before Dr. Ballard met with the governor,” the Daily Times reported from the AP wire.

“All Wednesday night mother lay awake in her room in the Texan Hotel,” said Gray’s son, 15-year-old Henry. “The Stephen F. Austin Hotel is just a block away and throughout the night we heard the music of the jazz band at the ball Mrs. Ferguson was attending.”

Prison officials told AP that Gray had grown “visibly nervous” through the day of August 6.

A reporter who got in to see him described Gray as “thin and gaunt, leaning against the bars of his cell, chewing almost constantly on the stub of an unlighted cigar.”

In the end, the nerve of the Iron Man broke.

At 9:15 the night of August 6, facing execution before dawn, Gray was passed a telegram from his wife.

“I’ve done all I can,” it read. “I hope to meet you in a better world.” It was signed, “Mother and Boys.”

The condemned man dropped his head and sobbed.

Prison barber M.L. Brown, a friend of Gray’s from their better days in Mt. Pleasant, was serving time for receiving and concealing stolen property. Around 10 p.m. he went in to shave Gray’s head and left leg, “where electrodes would be fitted after he was strapped in the chair.

“Both men wept bitterly as they bade each other goodbye,” read the Dallas Morning News account of the execution.

After being shaved in his cell, Gray asked to keep a large photo of his boys and wife as he was moved into his last holding cell. It’s been surmised that he used the picture to smuggle in the straight razor with which guards discovered he’d slit his throat just after midnight, August 7.

Clubbed into submission, “protesting his innocence and bleeding profusely, the condemned man was dragged to the death chair,” reported the Daily Times account.

Among those witnessing the execution were the Titus County’s new Sheriff Sam Hess and four deputies.

“I didn’t murder Ottis Ballard,” Gray said as he was strapped in the chair. “Men, I’m sick,” he said, as a brine-soaked helmet was strapped to his head.

The day after Gray’s graveside service in Dallas, the Dallas Times Herald reported that Texas Ranger Lone Wolf Gonzaullas, who’d twice arrested Gray and who’d guarded him during his murder trial, was among his pall bearers.

“What had been a bitter hatred on the part of Gray, in the later days turned into a strong friendship,” the Times Herald reported. The story included an account of a mysterious woman who appeared at the cemetery with flowers passed to an attendant with the explanation that Gray’s widow should know “there is a mother in Dallas who can appreciate their ill fate.”