War brought munitions plant to lake shore

MARSHALL – The last time Russian agents were in town – that we know of – began sometime after December 8, 1987, when President Reagan and Soviet Secretary Mikail Gorbachev signed a treaty “to eliminate an entire class of nuclear missiles,” as reported by Gail K. Beil. In writing the history of the Longhorn Army Ammunition works, she credits Marshall News Messenger writer and World War II vet Max Lale with the research work.

“One of his first assignments at the News Messenger was writing a comprehensive history of Marshall and Harrison County,” she said. “The piece grew to 32 pages and included everything from agriculture to weapons of mass destruction.”

The Russian agents came as witnesses to the demolition of some 700 solid fuel “Pershing I & II” rocket motors produced at what had been a cold-war era top secret “highly guarded, intensely classified area that was, for the most part, completely self sufficient,” Beil wrote for the East Texas Historical Journal in 2007.

The European press was among an entourage of reporters who followed Vice President George H.W. Bush and the Russians to the remote site in the wilds of Caddo Lake bayou on September 8, 1988 to watch as the first rocket motor strapped into a harness was fired, burned out and beaten to bits by the bucket of a bulldozer.

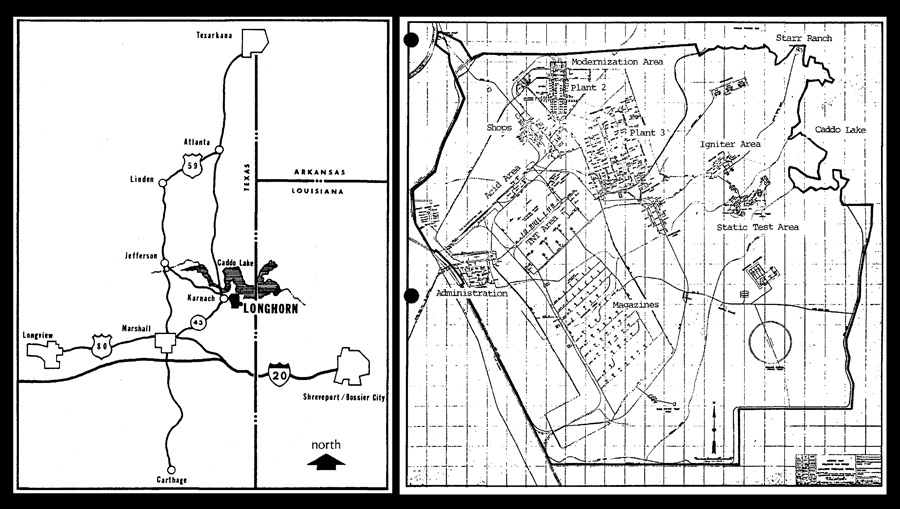

Behind barbed-wire topped fences securing thousands of acres, the rocket manufacturing facilities were a second phase of military production facilities built at the beginning of World War II near Karnack, an unincorporated community in rural Harrison County.

During World War II, when they first began producing dynamite making Harrison County a potential military target, some 150 concrete-bunker type production buildings were strategically spread out over 14 square miles, lessening the odds that any attacking force could get everything at once.

The first manufacturing era ended with the end of the war.

Next came the rocket motors designed to deliver nuclear warheads built during the arms race with the Soviets, its Cold War phase of operations.

The Reagan-Gorbachev “Treaty of Intermediate Nuclear Forces,” in which the two nations agreed to eliminate a mid-range class of nukes, was the beginning of the ammunition plant’s end.

Beginning in February, 1988, and “every six weeks until May, 1991, a team of Soviet scientists, military officers and KGB agents arrived in Marshall, occupied a special ‘secure’ wing of the Ramada Inn and remained for a month,” Beil reported. “When their job of witnessing the elimination of the missiles ended each day, they were free to go anywhere in the county except into private homes. Trips to Wal-Mart and automobile showrooms were a favorite.”

The Russians favored services downtown at Saint Joseph’s Catholic Church, she said.

Thirty one years later on a tour of an industrial park 13 miles away, Marshall Economic Development Corporation Executive Director Rush Harris slowed to a stop at the edge of the parking lot of an empty building where shotgun shells had been made before the company making them was bought by investors who moved manufacturing off shore.

For any number of reasons, he said, “Harrison County has a history of being the place picked to manufacture things that go Boom!”

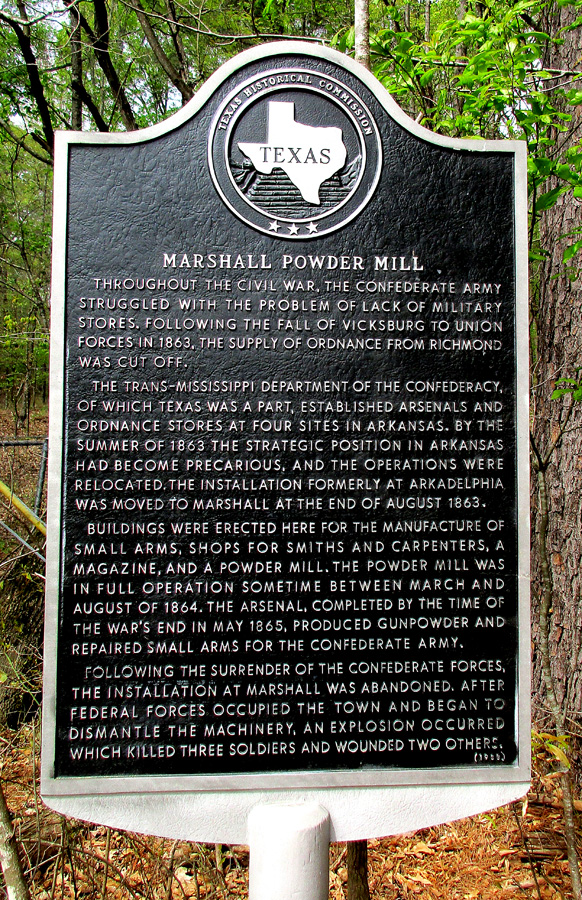

During the Civil War the Confederate command moved munitions manufacturing from Little Rock to a more secure location in Texas. When it was over, there remained “at least 60,000 pounds of canon powder and a quantity of fixed ammunition” in the powder mill at the edge of town, reported the June 2, 1865 Texas Republican.

“The same editorial said that Major Alexander, builder and Commanding Officer of the Marshall Powder Mill, was still in the area and had provided a demonstration to the local population of the dangerous nature of the remaining powder which citizens of the town were apparently looting, says a 1996 report in the Journal of Northeast Texas Archaeology.

“After Federal forces occupied the town and began to dismantle the mill, an explosion occurred which killed three soldiers and wounded two others,” reads the state historical marker at the site.

Eighty years passed.

America had yet to be drawn into the second World War when the army approached Saint Louis-based Monsanto about manufacturing TNT in northeast Texas. So eight days after the Japanese bombed the American fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, everything was in place to announce the location for construction of Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant.

Thirteen days later, on December 28, the army authorized Ford, Bacon and Davis, Inc., of New York City, to design and supervise construction of the Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant.

In less than a month, the army was feeding required paperwork through the court system, tidying up legal ends.

“One hundred and twenty eight defendant landowners have been issued notice by army engineers here of pending acquisition of 11,000 acres in the Caddo Lake region of northeast Harrison County, near Marshall, for the site of the $23 million federal TNT plant,” the January 22, 1942 Denison Press reported.

“The legal action was technically a blanket condemnation for all acreage sought for the federal project to simplify work of acquiring the tracts,” the newspaper said.

At that time, U.S. Representative Lyndon Baines Johnson of Texas, “a favorite of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” notes Gail Beil, had recently married Claudia Alta (Ladybird) Taylor, the daughter of “Thomas Jefferson Taylor, who happened to own a great deal of the land involved and assisted in the purchase of the rest.”

The War Department ultimately purchased 8,919 acres, more than a third of which belonged to LBJ’s father-in law. His general store in Karnack, “T.J. Taylor – Dealer in Everything,” was a landmark on U.S. 43, the road to Marshall.

“He’d made a name for himself as a political powerhouse by snaring the second state park established in Texas, Caddo Lake State Park,” wrote Gail Beil.

Production at Longhorn began October 6, 1942. Thirteen days later, at 12:20 p.m. October 19, the first flake of TNT was produced. At the height of its wartime production, there were 1,518 employees.

Within days of Japan’s surrender after nuclear bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when wartime production ended on August 15, 1945, Longhorn had made more than 200 tons of dynamite. A skeleton crew of two officers and 32 civilians remained when the military took control of the plant as a “standby installation” on April 23, 1946.

From February, 1952 until March, 1956, the plant made “pyrotechnic ammunition” used in the Korean War.

The end of production for the Korean War dovetailed into a 1956 private-sector munitions manufacturing study conducted by Thiokol Chemical Corporation, which had already landed two contracts to operate in military manufacturing facilities in Alabama. The study concluded that the Longhorn site was perfect for production of solid fuel rocket motors.

“Whether Lyndon Johnson’s position on the Senate Armed Services Committee had anything to do with the ultimate decision to make rocket motors on the banks of rural Caddo Lake” remains speculation rising from a “discussion of contractual arrangements “concerning facilities construction, as mentioned in a brochure cited in Beil’s footnotes.

LBJ became president with the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

In 1964, Longhorn was funded with $141 million for making rocket fuel. Employment soared, peaking at near 3,000. Then there was the disarmament treaty leading to the plant’s closing in 1992.

Presently, Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge is the subject of an Environmental Protection Agency “case study telling the remarkable story of the continuing cleanup of the Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant Superfund site of 8,000 acres including a “pristine mature flooded bald cypress forest, one of the best-preserved such ecosystems in the United States.

Open from daylight to dark, the refuge is crisscrossed with a geometric maze of roads in varying states, some open year round to hikers and bird watchers, some open seasonally. Occasionally, routes pass remnants of the concrete ruins of the World War II facilities.

In any internet search of contemporary tales of Caddo Lake, Harrison County and Marshall, you’ll run across Jack Canson. A native son, after his military hitch Mr. Canson opened a career as a political strategist that morphed into west coast screen writing.

His return to East Texas is noted in the Region 6 EPA case study report as one of the locals who “collaborated” to preserve one of the Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant’s original facilities in tact, a guard house from 1942. Originally slated for demolition, now it’s a visitors’ center.

The EPA identifies Mr. Canson as a member of the Greater Caddo Lake Association and the Caddo Lake Institute, a naturalist-driven entity that soared to life on the wings of Don Henley, as in Don Henley, the rock legend anchor of The Eagles, whose celebrity played to environmentalist and preservationist interests in the dismantling of the Longhorn plant.

At the 2009 opening of the Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Mr. Henley addressed the crowd and Mr. Canson said the visitors center showed that “we have all moved past the conflicts we had in the early days.”

For now, the end of the era of things that go “boom” is no more or less than a matter of fact for Rush Harris, the local face of an economic development office with an inside out approach to its mission.

The charter board of the Marshall EDC was created specifically to recruit a trade school, making education and training of a regional workforce a priority.

Acquisition of land for an industrial park came only after the town landed Texas State Technical Institute, a trade school with a unique offer.

“They’ve got half a dozen associate degree or certificate programs that come with a guarantee,” Mr. Harris said. “If you can’t land work making $50 grand a year straight out of the program, they’ll refund your tuition.”

TSTI’s education mission is intentionally directed at training next-generation work forces. Programs change with changes in the job market – presently, the utility lineman program’s booming with the industry focus on the electrical grid, Mr. Harris said.

Graduate one day, clock in the next.

A part of the town story, Mr. Harris said, is the pro-active support of education.

Arriving in 1910, Baptist minister W.T. Tardy found Marshall “a substantial old town spread out over its seven hills and manifesting evidences of continued growth,” as noted in his autobiography, Trials and Triumphs.

He had more to say about the church he’d been called to serve, where he found a congregation that “shrank from burdens, winced at hardships and complained loudly when pressed by imperative duties.”

It was after attending a local fundraiser for Southern Methodist University that Reverend Tardy found himself persuaded that education was the answer to the apathy he’d encountered.

A pair of locals, Marvin Turney and P.G. Whaley backed him with cash and in his book the reverend described searching for a location for his school, a search “coming to rest upon the crest of VanZandt Hill, the location for the Baptist college that opened in 1916.