Personal code pitted farmer against lawman

By HUDSON OLD

Journal Publisher

MT PLEASANT, TEXAS—When the lawmen were the outlaws, they were hard to beat.

But that’s how it was in Titus County during Prohibition.

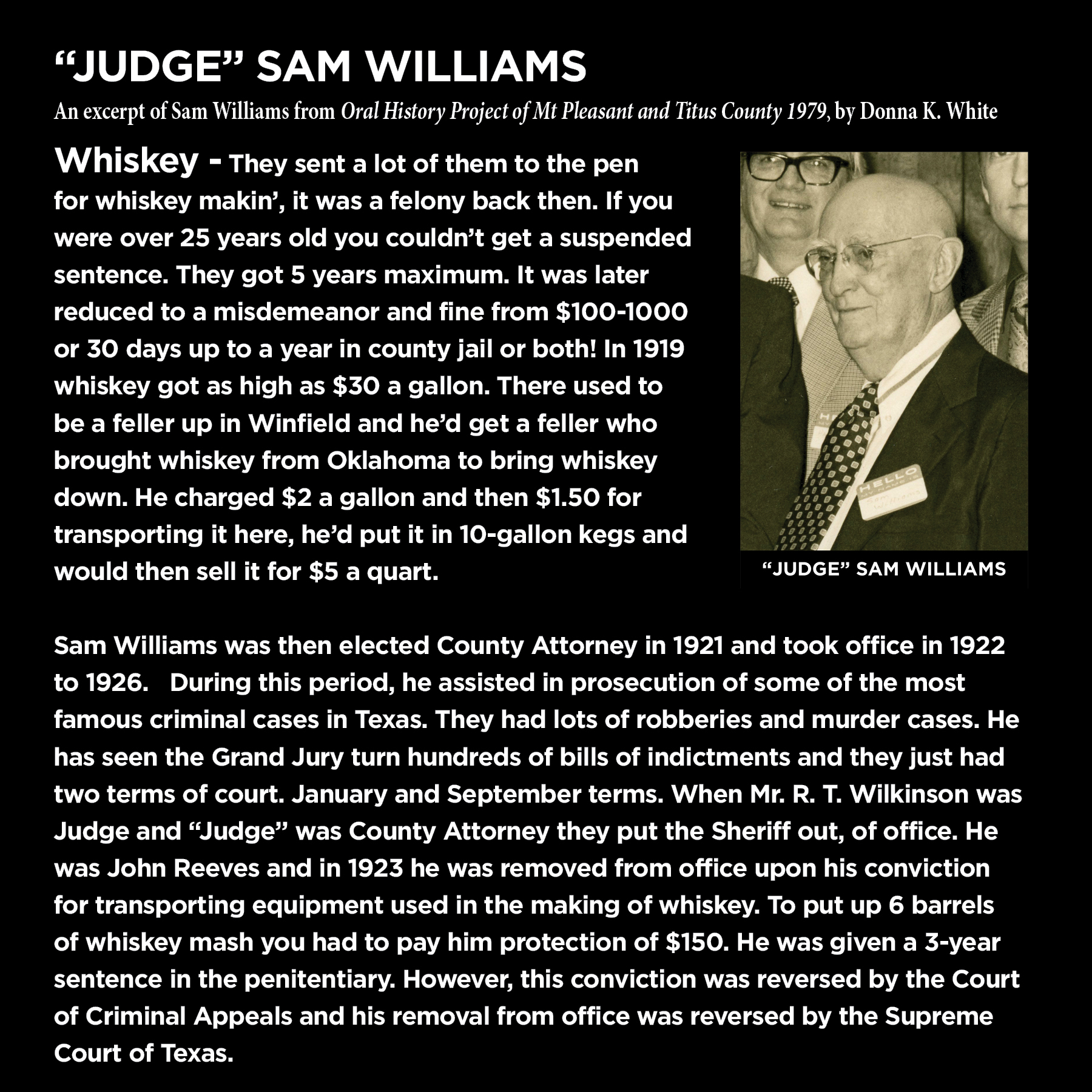

After America outlawed whiskey in 1919, the sheriff here turned played godfather to the whiskey makers at $150 “protection money” for each six barrels of whiskey the moonshiners put up, according to a Mt. Pleasant Library oral history project getting the inside story from Judge Sam Williams half a century after it all happened.

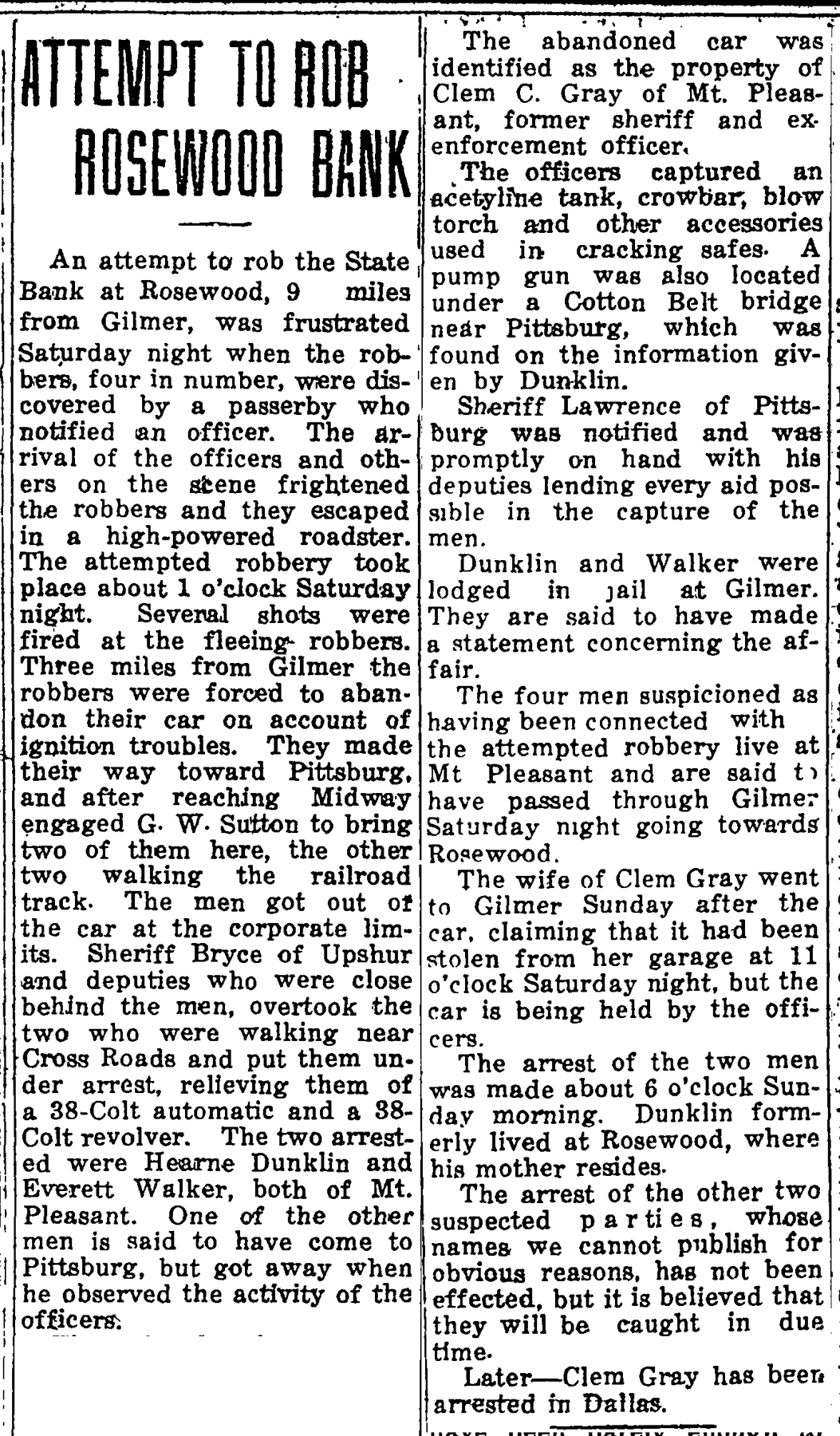

Except for another double crossing lawman gone bad, Sheriff John Reeves might never have been collared. He was backed into a corner after cops in Upshur County identified Clem Gray as the leader of a safecracking gang burglarizing a bank in Rosewood, eight miles west of Gilmer. The investigation that followed linked Gray and associates to an earlier bank job in Cookville.

Sheriff Reeves had no choice but arresting Gray after Texas Ranger Captain R.D. Shumate tracked him to the Terminal Hotel in Fort Worth. On the trip back to Mt. Pleasant, Gray slashed his own throat with a “safety razor blade which he had secreted in a postcard folder,” reported a June 8, 1923 Pittsburg Gazette story picked up from the Dallas Times Herald. “Before he could inflict serious injury, Deputy Allen Seale caught his arm and wrested the dripping blade from his fingers.”

A decade before, in May, 1909, Clem Gray was hired as a night policeman in Mt. Pleasant. He was a butcher by trade. His association with local law enforcement landed him a slot with federal officers who never managed to wipe out the moonshining boom Prohibition brought to Titus County, just thinned it down.

And blacksmiths prospered designing whiskey stills, wrote attorney and home-grown historian Traylor Russell, when bootleggers from “Dallas, Texarkana, Little Rock and Houston came to pick up carloads of whiskey.

“The whiskey element was so predominant that people found it to their advantage to go about their business and say nothing about the whiskey crowd as otherwise they knew their homes and barns would be burned and their stock killed,” Mr. Russell wrote in his 1965 first edition History of Titus County.

The Texas press seized on the story of Clem Gray who was once no-billed in the killing of a traveling salesman. Another time he was indicted for hitting a woman with a spittoon at a meeting in Mt. Pleasant and only months before a bloody ending that began with his arrest on the Rosewood bank charge he got busted running whiskey through Dallas.

“Grand Jury Petitions Removal of Sheriff,” read the headline of a June, 1923 story describing “sensational developments Wednesday afternoon when a petition was offered to the Court asking the temporary suspension of Sheriff J.J. Reeves” while the jury investigated allegations against him.

As Clem Gray was going down, he had everything he needed to take the sheriff with him. The lawman turned whiskey runner and safe cracker, Clem Gray had “been before the grand jury several times during the past two weeks,” said the story of the grand jury asking the court to remove the sheriff from office.

The sheriff had betrayed him, and now Clem Gray rolled over on the sheriff – the grand jury’s petition alleged that it was Sheriff Reeves providing the whiskey Clem Grey was running to Dallas.

Clem Gray was ultimately executed for killing one of four accomplices he feared would testify against him in the bank burglary trial.

These were dangerous people and they were engines powering the price of corn whiskey to $30 a gallon.

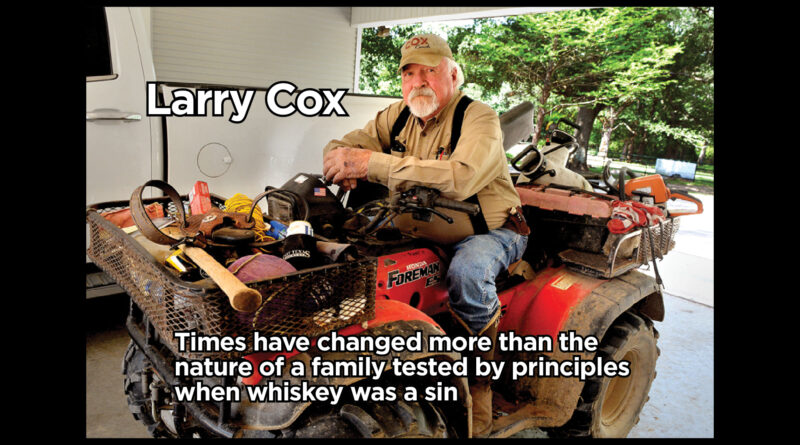

“Bud Hester wasn’t scared of ‘em,” said Larry Cox, a claim meriting investigation considering the story.

“Or the source,” observed retired Texas Ranger Brantley Foster, who publically questions Mr. Cox’s recall of two patrons in a convenience store whose deportment Mr. Cox says the Mr. Foster adjusted.

“It was something that needed to be done,” as Mr. Cox remembers, “and it was an out-of-state deal. We took our horses and rode up in the mountains on a vacation.”

In a Prohibition-era hand-me-down Cox family account, Bud Hester hated whiskey, whiskey makers and whiskey runners.

It might have been summer because Bud’s daughter, Maggie Hester-Cox, remembered the kitchen window being open at breakfast so when a hen squawked, they heard it.

“Her daddy went out to see what disturbed the chicken,” Mr. Cox picking up the thread of the story from his mother’s childhood memory of the man her daddy called Reeves, a name and event recalled because of the way her daddy spoke, a menacing tone laced with uncharacteristic cursing.

“When he went out he caught sunlight hitting a whiskey jug they’d planted in his yard,” said Mr. Cox. He went in for his rifle.

“Para Lee,” he told his wife, “the law’s coming,” and he went out and got the whiskey and brought it up on the porch. Suspected of providing tips to revenuers, Mr. Hester understood at once he was being set up.

“He waited there on the porch with his Winchester across his lap,” Mr. Cox said.

It happened exactly as he said except when the lawman got out and looked where the whiskey was to have been, it wasn’t there.

“I know why you’re here,” Maggie’s father said. Depending on whether it was 1922 or 1923, the two years Reeves was in office, she was either 8 or 9.

“Here’s your whiskey,” her daddy told him, and when he was done dressing the sheriff down, Mr. Hester ordered him off his place and told him to never return.

Nobody disturbed the Henry Franklin Hester family after that.

It was a hundred years after that, searching from his console at Journal Mission Control, Sam Ferguson found Titus County Sheriff John Reeves in a transcript of the Judge Sam Williams chapter in the Mt. Pleasant library’s oral history.

Sammy tracked him into cyberspace.

Fast forward.

“Ex-Sheriff Gets 3 Years in Pen,” said the February 1, 1924 headline over a story draped with news pegs – in a single day Reeves had been convicted of corruption, posted bond and announced intent to appeal. And though removed from office, he’d filed for re-election as sheriff.

His conviction was overturned. He ran third in the sheriff’s race but he got back on as a deputy featured in the news again in a 1925 episode in which he declared he’d refused the offered bribe but then been overpowered in the successful escape of a prisoner from the jail he’d been guarding.

That’s about it.

Now retired, Mr. Cox has two longhorn steers on 600 acres near Cookville.