1959 movie makers brought stars to Sulphur River scene

By HUDSON OLD

Journal Publisher

CLARKSVILLE – When movie director Vincente Minnelli got here, he went to the barbershop asking where he could find hounds for a critical scene about a hog hunt.

Garland Jaggers sent him back south across the Sulphur River into Titus County to find Tom Boy Franks.

One of four Franklin County Jaggers who made barbers, Garland had migrated to Red River County and cut hair on the Clarksville town square. Vernard Varley owned the barbershop. He was a childhood friend of the writer whose work ignited Metro-Goldwin-Mayer’s (MGM) imagination, said Jack Herrington, a retired lawyer who was one of a handful of Clarksville high school boys who worked on the Home From the Hills movie set in Sulphur bottom in the summer of 1959.

Tom Boy lived a mile or so south of the river. In that way barbers know things, Garland Jaggers knew about his dogs.

“Garland was a friend of my daddy’s,” said Tom Boy’s son, Tommy Franks. Tom Boy was the son of Guy Franks, who’d come from Louisiana to where his sons and grandsons still live. Sometime around the turn of the 20th century, he bought land and a cabin on the ridge between White Oak Creek and the Sulphur.

Past a fence separating pasture from the manicured lawn about the home Tommy’s son built next to his, the remnant of the cabin that pre-dates Guy’s arrival is nestled in a thicket. Tommy’s been told the single-room cabin was built in the 1850’s.

Cuts in the lumber used for the rafters show where boards were hewn with a broad axe.

“Whoever built it put it together with pegs,” Tommy said, one of scores of stories forking off the account trailing back to his daddy answering a movie maker’s call for hounds.

The script based on Clarksville native William Humphrey’s first novel, Home From the Hill, called for leading man Robert Mitchum to keep among his hunting dogs “one of the fabulous, blue-spotted, glassy-eyed Catahoula hog dogs, sometimes called leopard dogs, which he had hired stolen for him and named Deuteronomy, after passage 23:18: ‘Thou shalt not bring the fee of a prostitute or the price of a dog into thy house,’ which the people of people of the Catahoula Louisiana Lake district interpret to forbid the selling of a dog,” he wrote.

Maybe there was something to it back in Louisiana, where both the Franks family and Catahoula hounds came from.

“In that old tradition, as I understand it, you couldn’t buy a Catahoula hound,” said Tommy Franks, “but somebody could give you one.”

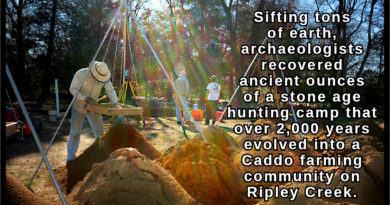

Another Louisiana native and a friend of Guy Franks now remembered in family lore only as ‘Butcher Knife Steve’ made Guy Franks a gift of two Catahoula pups that became the foundation stock for dogs the family first used to hunt and gather hogs during the free-range days along and between White Oak Creek and the Sulphur River.

Butcher Knife Steve was known for the quality of butcher knives he made. Names had meaning when Belcher family hogs running free range in the bottom were known as “Belcher Blues.”

The expression “Root, hog, or die,” comes from days when hogs turned out on free range were given but one way to live, foraging through an era that began ending when big money arrived, buying up and fencing off ranches.

“Turn a hog loose where he can root in the summer and eat acorns all winter and in a month he’ll be feral,” said Tommy Franks. People “ear-marked” their hogs. Guy’s mark was an “over slope with an underbit.”

Translated, that’s making an angled cut removing the top half of a hog’s ear and a notch cut in the underside.

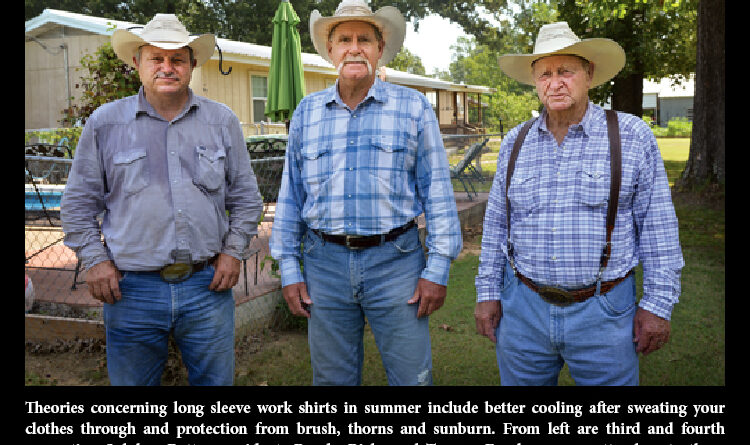

It was Robert Holt, whose father George landed “between the creeks” in 1918, who took me to see Tommy Franks. The free range era had begun ending before Robert, now 81, left Sugar Hill, a high spot between White Oak and the Sulphur. A new who’d bought up land in that country made the point clear on a day a younger Mr. Holt was in his boat, gliding quietly down the river on fall rise, hunting squirrels.

A man on horseback came riding to the river’s edge and demanded to know his name, which was none of the man’s business since he’d not introduced himself first. It was a clear breach of protocol, as was the fellow’s pulling a lever-action 30-30 he laid across the saddle, barrel pointed at Robert’s belly.

Appropriately impressed, “I’d have given him my social security number too, if he’d asked,” Mr. Holt remembers.

He grew up cutting logs with an axe alongside his father. Production soared when they got their first chainsaw, a machine designed before the age of litigation.

It was a two man saw with one handle above the engine and another on the cutting end at the tip of the bar.

More money than Mr. Holt had ever seen arrived with his first military payday after joining the air force, which was where he was when William Humphrey’s break-out novel made him the toast of New York and put Clarksville, East Texas and the Sulphur River on Hollywood’s map.

Hailed as an emerging writer in the Southern literary tradition of Faulkner and Mark Twain, Vogue magazine listed William Humphrey in its “gallery of international charmers among men” along with Marlon Brando, Leonard Bernstein and John F. Kennedy.

Traditions and legends of Sulphur Bottom as told in the novel include a haunting tale told by a character cast as the aristocratic Hunnicutt family’s hired man, “Old Chaucey.”

Don’t breathe the mist coming off the water, Chaucey warns Theron, planting a supernatural seed about the river in the mind of Captain Wade Hunnicutt’s only legitimate son, but only one among a number of the illegitimate offspring of the womanizing “Captain Wade.”

Portrayed by Eleanor Parker, his wife, Hannah, bears her husband’s infidelities like a badge of honor.

“He is my husband,” she said. “It is a wife’s duty to respect her husband, no matter how little he may deserve it – in fact, all the more as he doesn’t.”

The movie was out and the land was famous when Larry Ferguson, a fellow airman and a native of South Dakota, left the base in Amarillo riding home on leave with Robert Holt. They drove all night and passed over the Sulphur River into Titus County about sunrise.

“It was the fall of the year, one of those mornings when the air’s cooler than the water,” Robert said.

“It’s just like in the movie,” the South Dakotan said, awed and wondering at the nature of vapor condensing into a cloud hovering low over the water as they passed over the U.S. 271 bridge.

In Home From the Hill, Mr. Humphrey describes hogs in Sulphur Bottom being so dangerous as to have legendary standing in lore passed on in his account of Captain Wade.

Director Minnelli turned the fabled account of the Captain killing “the last wild boar in East Texas” into a pivotal scene in the movie, the set up for the climax of a generational story ending in tragedy, revenge and blood lust.

Young, genteel, born into privilege and groomed in the ways of a man, in the closing chapter of the story, Theron Hunnicutt – played by a young George Hamilton – is driven to a murderous rage demanding vengeance as he trails his father’s killer into the wilds of Sulphur Bottom.

A jealous husband had blown the captain’s head off with a shotgun.

“I don’t know that it’s so, but it’s said the novel’s based on some mix of Red River County families,” Tommy Franks said.

Born dirt poor in 1924 into a family that moved when his father couldn’t afford the rent, to describe the men who settled the bottom – that is, characters built by a native writer knowing the way of the early-settling Franks family men even if he didn’t know that particular family by name — William Humphrey flashed back to memories of the Clarksville town square on Saturdays, the day farmers came to town.

In the Saturday crowd, he said, you might find “one of two of the special few” who often stayed away six months at a time, the “year-round hunters, silent-footed and quick-eyed as the game they hunt and trap, gaunt, sallow men, skin dyed yellow from malaria . . .”

From among all the hounds in the country, the barber who steered the movie makers to Tom Boy Franks made a star of a blue-eyed Catahoula hound named Rowdy.

Catahoulas are “assertive” dogs, “often having issues with interdog aggression and an intolerance to strangers,” says the internet, a claim Tommy Franks affirms.

“Rowdy was scarcely tolerant of my daddy touching him, much less anybody else,” Mr. Franks said. Up until playing the lead dog in the movie hog hunt, Rowdy was employed in the more practical matter of gathering free-range hogs.

In life as it was when Tommy Franks was growing up, Rowdy led the pack that needed no instruction beyond seeing the Franks men on horseback, mounted and riding into the Bottom.

The dogs took the lead, baying hounds trailing hogs.

“The hogs answered that bay like a call,” Tommy Franks said. “It meant we were coming, bringing corn. The old sows would gather up pigs and bring them to the dogs, knowing they were going to get something good to eat.”

Once rounded up, dogs and horseback men drove the hogs to pens built in the bottoms.

Until his movie call, it was all the work Rowdy knew.

“This scar here,” Tommy Franks said, rolling up his sleeve, “this is where Rowdy bit me once, before we came to an understanding.”

Besides his dog, Tom Boy provided the hog for the hunting scene, a possibly somewhat Hampshire, the breed his father favored turning out in the bottoms. By the time they made the movie, his Hampshires had for generations been crossing with “pine rooters,” as Tommy Franks calls the wild hogs that were native to the country a century back, when Guy arrived.

After time running free, a Hampshire hog with a touch of long-snout pine rooter in his blood tended to have a thorny disposition akin to a Catahoula hound.

“When we were boys, me and Scooter Parish were playing, using hot shots to provoke a sassy boar we’d penned,” Mr. Franks turned the movie story down a tangential trail. “That pen was head high, so we’d just climb the fence every time he turned to get us. Finally, we had him so mad and frustrated he jumped the fence and was gone. We’d have gone easier on him if we’d known he was such a high jumper.”

It’s a moment remembered because Guy Franks dismissed the story as unlikely, figuring instead that the boys had for whatever boyish reasons turned the hog out. Short, slight a wirey, Guy was intolerant of foolishness.

“That is,” his son said, refining the point, “unless it was foolishness of his own making.

“Once when old Sam Williams was running for office, he told me a story about the first time he met my daddy. He’d come out politicking and found a group of men watching gathering to meet him, my daddy among them.

“When he stated his business, he asked if anybody knew where he could find Guy Franks, a man he’d been told he should meet.

“‘I know him,’ answered Guy Franks, ‘a little sawed off fellow, stands deep in his boots.’”

Sam Wilson, who had a pickup with sideboards, was hired to transport the movie boar Tom Boy Franks provided for the scene with Rowdy playing the lead among a pack of hounds. Bill Bivens, who lived at Cuthand on the Red River county side of the Sulphur, had dogs in that scene, too, Tommy Franks said.

“I remember this because when Sam Wilson got back to our place late that afternoon, there was black paint all over the sideboards of his pickup bed,” Tommy Franks said. “He said when they found out they wanted a black hog they spray painted him.”

The novelist William Humphrey and his mother left Clarksville when he was 13, the year his father was killed in a car wreck. They went to Dallas, where the widow found work. Mr. Humphrey finished high school there.

Before striking out for New York hoping to sell a play on Broadway, Mr. Humphrey attended Southern Methodist University and the University of Texas, but quit before earning a degree either place.

His play struck out on Broadway.

For a time, he worked as a shepherd tending goats in exchange for a place to live. His writing career gained enough traction to land him work as a teacher after The New Yorker began publishing his short stories.

Home From the Hill launched him.

“Seldom have the sins of the father been visited on the first-born as wretchingly as in this dark and beautiful first novel,” wrote the New York Herald Tribune in 1958, when at the age of 35 William Humphrey’s first of 13 books was published. “Seldom, for that matter, is a novel, first or otherwise, published which combines pure narrative magic, exquisite sensibility and an uncompromising masculinity in the way Home from the Hill does.”

The Hollywood magazine Variety reported that Mr. Humphrey was paid $750,000 for the movie rights.

“Unfortunately,” he said, “there was an extra zero in that account.” But, $75,000 was enough to buy a farm in rural Hudson, New York, with enough seed money left over to make it through to his second novel, The Ordways, a 180-degree turn into comedy-laced satire, another story emerging from his memories of Clarksville.

Unlike Norman Mailer and the other noted authors of his time, William Humphrey was not a promoter, but a writer who let his work speak for itself, one who made no effort to market himself.

His work was largely out of print until picked up by the Louisiana State University Press in a series billed as “Voices of the South,” new printings of novels recognized for regional significance.

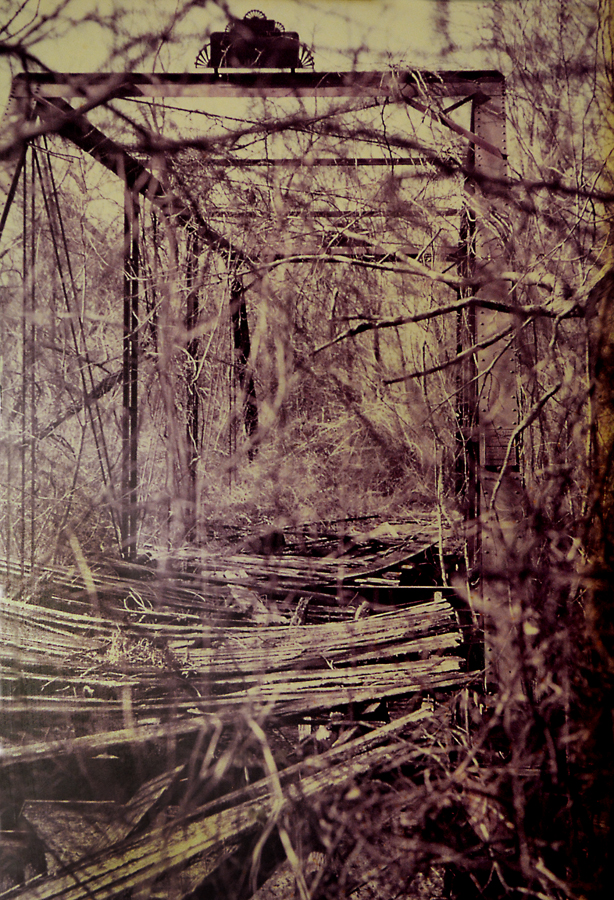

Physician, wordsmith and Texas Historian Dr. Tom Sloan launched this account after discovering an on-line reference to an old “iron bridge” where 16-year-old Tommy Franks caught his first look of director Vincente Minelli’s daughter on the only day Tom Boy allowed his son to come along and watch.

“Liza Minelli was skinny and tall, nothing but eyes and legs,” said Tommy, who was more impressed with camera crews filming a scene in which Theron chases his father’s killer, played by Everett Sloane, across a bridge that once spanned the Sulphur at a high bank named Hart’s Bluff.

There’s some internet confusion about the coordinates of the “Old Iron Bridge” Dr. Sloan found on line. There’s an old iron bridge at that spot, one by-passed in the 1980’s when the Texas Highway Department sprung for a new concrete bridge across the Sulphur.

But it’s some distance west of the abandoned bridge filmed in the movie.

“My grandfather helped build the one in the movie,” said Franklin County resident Mary Lou Mowery, a native of Red River County.

A wealthy land owner whose farm spanned the river when she was growing up, Austin Bishop worked with the Corps of Engineers to locate a bridge at the place the river was least likely to wash it away.

The bridge lasted longer than the road across the Bishop family’s Hart’s Bluff Ranch. Within a decade of completion, the river carved a new course washing away the road north of the bridge.

By the time the movie was made, the bridge passed over an “oxbow lake” that filled with a swift current when the river flooded and dried up in summer low water, when the river fell and only flowed through the new channel.

From the Titus County side, winter and spring rains continually changed meandering routes to the old bridge, which became a favored swimming hole with rushing water when the bottom flooded.

“There never was much of a road to it to start with,” said Robert Holt.

“Before all the timber was cut and it grew up in thicket, when everybody was running cattle and hogs and horses in the bottom, they kept the forest floor clean,” he said. “When we were kids, Richard Haren had a 30-model Chevy truck he drove all over the bottom in dry weather. In the summer, you could drive to the bridge. When it was wet, you knew better than to try.”

When the water was up, the same gang swam in the swift overflow rushing beneath the bridge with a framework like a jungle gym serving as a multi-level diving platform.

“I remember big flood on a good day for swimming when we were daring each other to try swimming across,” Mr. Holt said. “We weren’t sure we could make it so we threw our dog in, figuring if he could make it across so could we. He kept swimming back to us and we kept throwing him in until he finally gave up and swam across.”

Taking heart, the boys spent the afternoon swimming the cross current, making a game of guessing how far downstream they’d wash before making the Red River County shore.

Now 79, the retired Clarksville attorney seconding accounts of a barber shop connection linking MGM to Tom Boy Franks, Jack Herrington worked to open a route for 17 trucks packed with props and movie gear shipped from Hollywood to film at the bridge.

While that was in progress, Mary Lou and a college roommate came to watch a cattle working scene filmed at her grandfather Bishop’s corrals. The man she later married was one of a handful of locals picked as extras.

Dashing and rugged, the late Joe Edd Russell was seen walking a catwalk over the dipping vats cattle were pushed through.

She remembers George Hamilton as Captain Wade’s son, Theron, in a scene where he was perched in a tree stand on a hunt, clacking deer antlers to “rattle up” a buck. It was raining.

“They pumped water from a tank to make the rain,” she said.

Attorney Herrington was the rainmaker.

“I was about ten feet higher in the tree with a shower head on a garden hose,” he said, being one of the handful of local boys drawing $3.80 an hour, more than four times minimum wage.

He had connections.

His parents, Tom and Dixie Herrington, had a cabin where the Clarksville Country Club golf course nestled into the shore of North Lake.

“When MGM came to town, they hosted a steak dinner at the cabin for the big wigs,” he said, “all the movie execs and the local politicians.” When filming started, he was one of the kids lighting yellow smoke bombs to create “fog” rising beneath the bridge.

“We made earth banks to hide behind,” he said. “We had cases and cases of smoke bombs.” Not all were burned for the movie. For the rest of the summer, some nights yellow smoke blanketed the town square.

Behind the scenes, a young Mr. Herrington enabled some of the cast and crew.

“For some reason, I was picked as the driver to take guys into town when they needed more cokes to mix with their whiskey,” he said. There was lots of down time for cast members, time to drink. “Every time I took somebody to town, they’d buy me a bag of peanuts. I ate lots of peanuts for a few weeks before it started raining.”

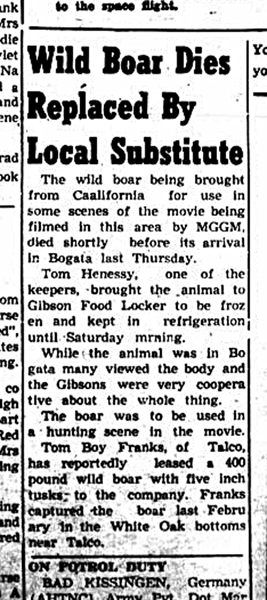

Sixty years later, recollections aren’t far off the mark in a story East Texas Journal production room manager Sam Ferguson found in the archives of the Bogata Times.

“Wild Boar Dies; Replaced by Local Substitute,” read a headline from the June 25, 1959 edition. “The wild boar being brought from California by MGM died shortly before its arrival in Bogata last Thursday.

“Tom Henessy, one of the keepers, brought the animal to Gibson Food Locker to be frozen. While the animal was in Bogata, many viewed the body and the Gibsons were very cooperative about the whole thing.

“Tom Boy Franks, of Talco, has reportedly leased a 400-pound boar with five-inch tusks to the company. Franks captured the boar while gathering hogs last February.”

A week earlier, the Times reported that advance crews had built a five mile road to reach the bridge at Sulphur Bluff.

“A landing field for helicopters has also been built,” the account said.

“A limited number of local people will be used in the picture. Joe E. Russell, an Annona rancher, will portray a ranch foreman.”

On June 26, a Clarksville Times headline said, “Rains Halt MGM Filming Two Days.” Some 80 cast and crew members were left to play cards in rooms at the Nicholson Hotel in Paris, which was “the nicest hotel in the country,” Mr. Herrington said.

While it rained, local game wardens Charlie Burnette and Bill Daniel guarded the location the paper said.

Identified then as an “assistant game warden,” Bill Daniel went on to become a Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife Region 8 Commander stationed in Mt. Pleasant, with 38 counties in his jurisdiction.

“Bill’s story about the movie was that Liza Minelli rode with him and Charlie, and he always stuck to it,” said retired Texas game warden Kenneth Hand.

The same story mentioning Commander Daniel and the rain added, “While no official statements have been issued concerning the time which the filming party will remain here, it was learned indirectly that probably only a few more days of work remain.”

As Jack Herrington remembers, from start to finish was but a matter of weeks, and cut short at that.

Two days of hard rain with cloudbursts of summer thunderstorms made roads into the bottom impassable while payroll drained the $75,000 budget for work in Red River County reported by the Clarksville Times.

Movie scenes calling for Southern Colonial Mansions had been earlier filmed in Oxford, Mississippi.

Inside shots were made on MGM sets back in Hollywood.

Then rain and mud in Sulphur Bottom closed the curtains on work in Red River County, Mr. Herrington said.

“Movie makers are creative people by nature,” he said. “When they couldn’t get back to the location, they packed up, went back to California, built sets and shot whatever else they needed on the lot at Metro-Goldwin-Mayer. I understand they built a mechanical wild boar.”

My mother took us cub scouts to sulphuric bottoms when they were filming The movie. We ate lunch with the movie stars. I got a autograph from George Hamilton for my mother. Thanks Stan Dickerson