Hand-picked venue scores a slice of Matteson legacy

DeKalb, Texas — There’s a mastodon vertebra found by a man from Naples next to the hand-cranked Japanese air raid siren above tribal spear tips in the replica of the Matteson farm commissary here at the Williams House Museum.

A cotton farmer turned trader, Worth Matteson became a collector who traveled to find whatever interested him and bring it home. He filled the farm commissary with it. When he ran out of room the collection spilled out to the Colvit Barn, a century-old hand-hewn oak masterpiece built in the days of hand tools on Hoot Owl Farm.

One time when he got home from a trading trip, Worth weighed his RV.

“He wanted to measure how much he’d brought back in pounds,” said his son, Worth.

Starting with Worth who came here from Illinois and built the gin at Laynesport in 1917, “there are five Worths,” said Janie Moser-Matteson, who married the third one.

In a satisfying chapter of his life, Worth was a man of leisure who’d left farm management to his heirs. He collected and traded whatever interested him. One time he built his own armillary sphere because that interested him.

An armillary sphere has an arrow like a wind vane pointing from a center of concentric metallic rings. Point it at the North Star and measurements calibrated inside the rings can be used to calculate what time it is. The one Worth brought home before he built one is now on display where his son and daughter-in-law felt it should be, in a museum.

Sometime after he died, Worth and Janie invited Michael and Carolyn McCrary out to the Colvit Barn, a structure so old and so massive as to have become a landmark on the highway north of DeKalb.

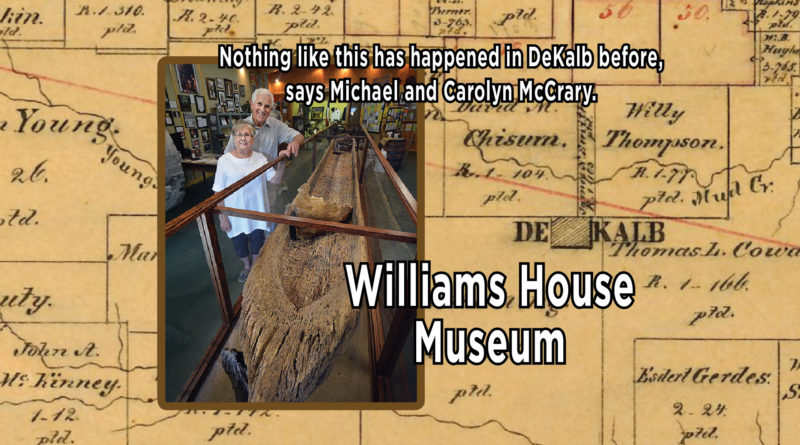

For 20 years now, Michael and Carolyn have manned the Williams House Museum in DeKalb, a nook in a universe better known in cyberspace. It doesn’t generate much local traffic. Most visitors come in off Interstate 30, purposely directed up U.S. 259 North.

“Local history at its best,” wrote John B, of Tempe, Arizona, after being routed to the museum by Trip Advisor.

Michael and Carolyn imagine a time when the museum might capture the imagination of educators booking school field trips to Williams House. In an 1839 edition of Little Rock’s Arkansas Gazette, Michael found an advertisement for lots in Laynesport, a 19th century landing in the paddle wheeler era on the Red River.

In the museum’s Red River exhibit are more than 20 ports he discovered upstream of Shreveport and on around the bend above Texarkana.

That mastodon vertebra was found near Spanish Bluff. The way Spanish Bluff got its name, that’s where the Spanish conquistadors built a fort overlooking the river. It’s on the Texas side, land presently claimed by Bowie County.

Spanish Bluff is where Thomas Freeman and Peter Custiss, the men President Thomas Jefferson picked in 1806 to lead an expedition into the new American lands of the Louisiana Purchase, encountered the Spanish. Outnumbered and outgunned, that’s as far upstream as the Freeman and Custiss expedition made it.

In Michael McCrary’s story of the river told in the Williams House Museum exhibit, the furthest upstream port was near Denison.

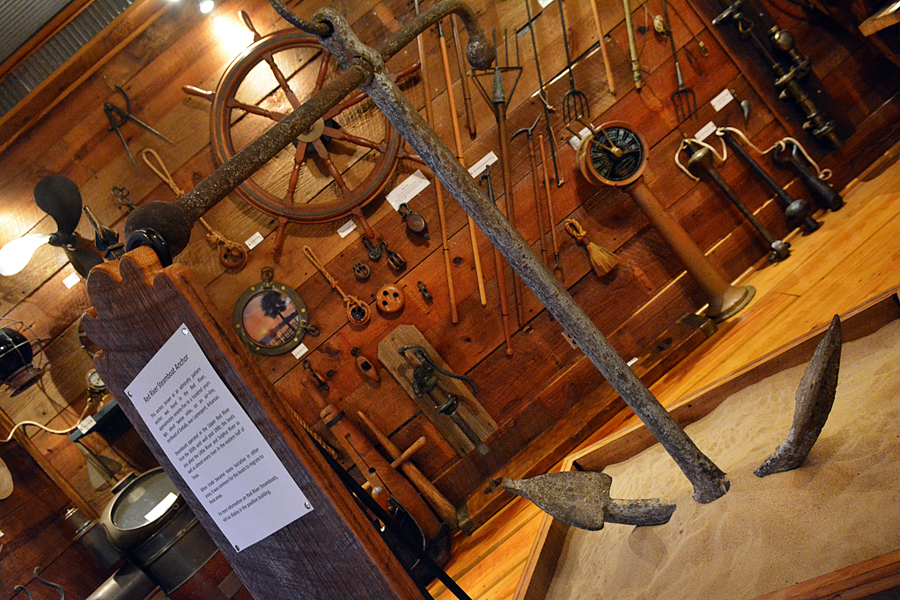

On display at the museum is a ship’s anchor dug from the mud near Laynesport.

Before it was given to the museum, the ship’s anchor figured into the landscaping on the lawn at the Worth Matteson place, where his family has farmed the Arkansas side of the river for more than a century now.

On the Texas side, the Moser family is known for cattle on Moser Ranch, though they’ve farmed as well.

In the 1960’s, Janie Moser met Worth Matteson at the rail depot in Texarkana. They’d both been visiting home and both were returning to school at Tulane.

“We were both there to catch the overnight to New Orleans,” said Worth. “Our families knew each other but that was the first glimpse I had of her.”

After they boarded, Janie retired to her berth in the sleeper car she’d booked.

Worth idled over a beer in the dining car before taking a seat in coach.

“We connected again when she came to the cotton gin with her father, who was there to see how many bales had come from his farm,” Worth said.

“That your girl?” one of the gin’s hired men asked.

“No,” Worth said, “but that’s not a bad idea.”

After Tulane, Janie enrolled in law school at the University of Texas. Given the lively distractions of New Orleans, Worth transferred to and graduated from the University of Arkansas.

He married Janie after she passed her bar exam in 1970.

One day, with children approaching school age, “I’m moving to town,” Janie said to Worth, a story presently causing both to smile as she ends a chapter there, where they built in DeKalb. For years, Worth commuted daily to work at the farm.

What had been the commissary and business offices during the share cropping era became his father’s warehouse, his shop. He opened an antique booth in a Texarkana mall.

When the Mattesons invited the McCrarys out to the Colvit barn, “We thought they were asking us out to pick something we’d like to have for the museum,” Carolyn said, not understanding it was an invitation to take everything they wanted.

One Trip Advisor review of the Williams House focuses on the “women’s card game” Ron B interrupted when he arrived. He goes on to describe the museum as “one of the one best things to do” in DeKalb.”

Her father-in-law’s interest as a collector went through periods, Janie said.

“There was a tool period. During his nautical period he haunted the Texas coast,” she said.

The barn the Colvit men built on the Hoot Owl Farm the Moser family later bought is functionally obsolete, the last of the barns built with corn cribs and a loft for hay.

Named for the last rail foreman who’d made it his home, the Williams House was an 1885 Texas & Pacific Railroad Section House.

Michael McCrary’s part in its restoration established him as the museum’s facilities designer and builder – a package deal coming with Carolyn. After building the first out-building, reason dictated that he build a cypress wood water catchment system channeling rainwater to a cistern.

A strange tree that prospers in standing water and flourishes in swamps, cypress is an oily wood with natural resistance to rot that would have been the preference of all common-sense pioneers dependent on rainwater where groundwater’s too deep for hand-digging a well.

There’s an authenticity about Williams House. There’s reverence for Americana, the hint of a story told in a period photo from Mutt Mays Texaco, otherwise left to the viewer’s imagination.

In summer, when it’s hot and stagnant, water in a cistern is a perfect habitat for growing “wrigglers,” little somethings swimming like germs vanquished by boiling. The cistern at Williams House is laid out to spill over into a natural draw draining the land.

Native son Dan Blocker, an actor known for his 60’s role on NBC’s Bonanza, is kept indoors alongside Huddie Leadbetter, better known as Lead Belly, a more obscure story further away in time.

Lead Belly sang the blues over women. He wrote children’s songs and he did time out on the Bowie County prison farm, land the Moser family bought after the prison farm folded. The museum story about him includes the part where he sang his way out of prison once, over in Louisiana.

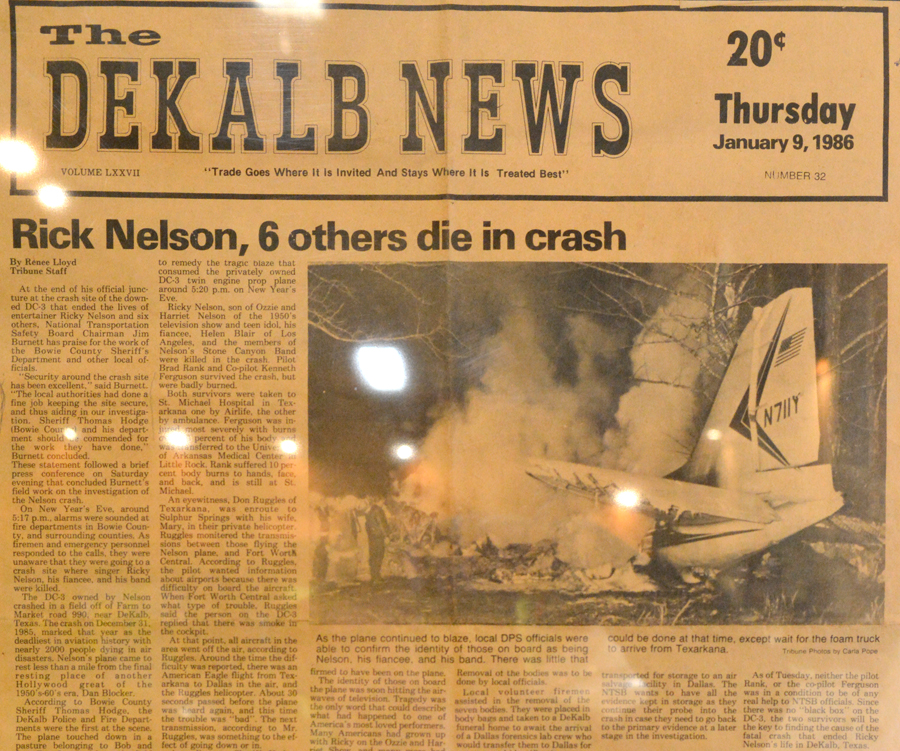

Williams House is a destination for that tourism niche following teen idol Ricky Nelson, the good-looking big brother from Leave it to Beaver. He’s not from here, but he died here one night when his plane crashed in the Sulphur River bottom.

He wrote “Garden Party,” and in its lyrics we learn that the good looking prototype of the straight-laced TV big brother grew into a free-spirited American folk singer, a gentle non conformist.

“If you gotta play at garden parties, I wish you a lot of luck,” he wrote, “but if memories were all I sang, I’d rather drive a truck.”

People not from here come to think about that while considering the piece of the wrecked fuselage of the plane that took him away, now there at Williams House.

In the museum replica of the Matteson Commissary, there’s also a “human yoke,” a European piece designed for carrying a load balanced across the shoulders, one of the hundreds of pieces Becky Buttram helped research and catalogue.

For some things, she wrote brief narratives and explanations. On foggy nights, New England sleigh bells rang notice of approaching sleighs.

Sheer tenacity driven by curiosity allowed Becky to identify a beautifully symmetric wooden piece, a spiraling sculpture with wooden blades, a “pod auger.”

She’s still searching for anything telling them what a pod auger might have been used for, how it worked.

There’s a hand-operated cotton ginning piece, the simplest possible design explaining how Eli Whitney did what nobody in a thousand years had done, which was figure out an economical way to process cotton which transformed cotton to wealth.

Probably half the Matteson collection is farm related, because that’s a part of what all of the Worth Mattesons have been and are. Worth the museum patron has passed management of farm operations to his son, Worth.

As for his father’s collection, Worth might have picked any museum he wanted.

So he did.

The Williams House comes with Michael McCrary, who lets his work speak for itself. Beyond passing the best of the collection for the museum, Worth had Michael take what he needed from the Colvit barn, hand-picking lumber, cannibalizing small corrugation sheet iron nobody makes anymore, things that shaped his vision for the interior of the Matteson commissary building.

The commissary exterior changes to something from a movie as you step through the door, track lighting igniting ambient light warmed by raw wood, framed by sheet iron over framework supporting directional lighting. Michael planed the century-old heart pine he used for flooring.

It gleams.