Texans search English Abbey for beekeeper

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal August 2017 Edition

By RON COUCH

Special to the Journal

A book about bees caused Jesse Wright and me to go to England.

Aboard the rental Mercedes we’d been issued in London, British alarm bells chimed politely. Accident avoidance systems programmed for highways expressed red-light concerns when we passed through hedgerows brushing the fenders, as if we couldn’t tell we’d lost the main highway and turned onto an English sheep trail.

The sheep gave it away.

Our search for the story of the Benedictine Monk who saved Europe through a life committed to perfecting the Buckfast Abbey Honeybee was off to a slow start. Mired in a sheep jam bringing to a dead stop opposing strings of traffic on a one-lane road, we had time to consider things we’d not expected to learn in England.

“How many sheep could walk abreast in the width of a one-lane road?” Jesse asked.

“Sheep lanes or car lanes?” I answered.

From Englishmen taking the opportunity to step from their lorries and stretch, we learned that somewhere up ahead, traffic coming from either direction along the narrow way had arrived at a front-bumper to front-bumper impasse. Each of the lead drivers became the representative charged with negotiating terms under which drivers in one or the other direction of travel would agree to back up to allow the opposing side to pass.

It’s a little known English tradition.

“Tally-ho!” I celebrated when our representative prevailed. Onward we oozed into the hinterlands in hopes of finding the lovely moor pictured in Brother Adam’s first book, the place where his work gave life to England’s honeybee royalty. A common laborer in the order of monks, he gave rise to a strain of resilient queens ruling hives of bees emerging from the threat of annihilation.

His swarms gave hope to beekeepers across the Old World when there had been no defense against the collapse of hives infected by the Isle of Wight plague.

At length, Jesse said, “Considering the range of worker flights, I don’t know that you can claim Brother Adam single handedly saved all of Europe.”

“Well not all at once,” I agreed. “But it doesn’t change the point. Do the math. Every third bite of food eaten times every person on earth since Adam times every spring honey flow since creation has depended on honeybees pollinating the plants we eat. Without bees we starve. It’s in the Bible. Look it up.”

“What translation?”

Led by the demonstrably flawed Google Maps navigation system diverting us to a Class B Road shortcut sheep trail to the monastery, we crawled along on faith, elapsed time approaching 14 hours since landing at Heathrow Airport. The relative ease of negotiating DFW traffic, boarding our flight and passing over the Atlantic at eight miles a minute was a fleeting memory.

“Who’d have guessed that instead of being in Terminal 5, the Heathrow Terminal 5 Hilton would be a 20 minute taxi fare from the airport?” Jesse wondered. Nice place, just not where the airport reference would lead you to think you’d find it.

“By Jove, what’s the matter with that? We’re learning English eccentricities,” I said, putting an educational face on the adventure of locating our first night’s lodging. Leaving the hotel in our rental some hours back, we’d taken a wrong turn at the first opportunity, circling back through the airport once before finding our road.

Gambling on a second spin around the traffic circle with roads leading out like spokes on a wheel, we got lucky. Successful navigation about England only begins with driving on the wrong side of the road.

Waiting for our line to move, Jesse said, “I got it. It’s another safety thing.”

“What?”

“It’s impossible to drive on the wrong side of a one-lane road.”

On a fine highway coming out of London earlier in the morning we’d had opportunity to air out the rental and discover its top speed of 46 kilometers per hour.

Using the same smart phone that opened our portal to the sheep trail, I ran the numbers.

“Jesse, if we were still in Texas we’d be clocking 28 miles an hour,” I calculated.

Problem solvers, we called the Mercedes rental office.

“Who’d have thought they’d come out with a cruise control option locking in a top speed?” Jesse asked.

“What will they think of next?” I wondered.

Soon after we learned how to de-activate cruise control, Google Maps alerted us to the Class “B” shortcut. Thinking of “B” as the grade that was always good enough in school, we assumed England had a similar system in road classifications.

Move back two spaces.

We were incorrect.

English travel tip: An “M” is a highway and “A” is a suitable two lane. “B” is anything else, including sheep trails wending through the English countryside.

We observed. We learned that grown sheep are leisurely, in no hurry, rather dull. Adolescent sheep are excitable, playful. Honk and they run and dance and jump and have fun.

For both sheep and motorists, life on a Class B English road affords time for the luxury of creating your own entertainment.

I’m retired. I already have time. I have searched for the end of the Internet. That’s where I found Clare Densley, the current keeper of the bees at Buckfast Abbey, buried deep in the bowels of the monastery’s website.

A lot of the Abbey website is committed to marketing a fortified wine made with grapes shipped across the English channel from French vineyards.

Sold as “Buckie,” the wine bottled at the abbey is infused with a potent pick-me-up shot of caffeine. Off the abbey website, a general Internet search for Buckfast Abbey reveals it as the focal point of litigation concerning Buckie, a wine currently associated with alcohol influenced, caffeine-driven, hyperactive “antisocial behavior, particularly in Scotland.”

“You’re making that up,” Jesse accused.

“No, it’s right here,” I turned the screen of my phone for him to see the travel column about the abbey I’d found in a back issue of the Lincolnshire Free Press.

“I can’t believe you’d think I’d make something like that up,” I said. Buckie’s the top grossing product of the abbey — $10 million a year.

Thinking of reasons the monks once were great beekeepers, I said, “Centuries before they made wine, the monks fermented honey to make mead.”

“Must be a Catholic deal,” Jesse said, a tone questioning holy men employing God’s bees for such purpose.

I said I’m retired but it was more like unemployed until six years ago when I first began reading and trying to understand the mysteries of “swarm intelligence.” It’s a complex weave of insect communication coordinating a natural – make that supernatural — universe in which life as we live it is, quiet literally, dependent on bees.

Smarter guys than me have figured this out.

A German born in 1898, at the age of nine Brother Adam’s mother shipped him to England and committed his life to the service of the Benedictine monastery. A “lay” monk as opposed to a “choir” monk, he began training as a stonemason. Judged too frail for the work, he was made assistant beekeeper.

Lay monks in those days were the abbey servants, the laborers, the carpenters and farmers, the cooks and maintenance workers, the builders. Choir monks are the traditional image of monks, ordained by the church, their lives committed to spiritual quests. For a thousand years at Buckfast, but with notable interruptions, monks have been singing to the heavens in the language of ancient chants, rituals that live to reveal the Light, to glorify the truth of God.

Brother Adam wrote three books about bees during a life in which he circled the globe to study and develop a genetic strain immune to the Isle of Wight disease decimating Europe’s hives in the 1920’s and 30’s.

Time was, when the monks lived closer to the earth, bees were essential for wax to make candles, for honey as a sweetener, for the making of mead. Pollination likely seemed a collateral benefit.

When I finished Brother Adam’s first book I went searching cyberspace for him, certain that I’d find the life story.

I might as well have been driving a Mercedes down a sheep trail. Providence intervened just as I was about to give up, making all the better the moment I found Clare Densley, nothing more than a modest note concerning her role as one of the Abbey’s 200 employees and the only beekeeper. Whipping out my trusty smart phone, I fired off an email telling her I’d read Brother Adam’s book but could find nothing more about him.

She warmed at once.

All the beekeepers in the world, all the innovative thinking, all the lifelong commitment made by those who understand and reap the benefit and all equipment developed to make bees more productive has been driven by people who get it. Bees don’t need us. We need them.

Nobody keeps bees without understanding there are things too perfect to understand, natural evidence of supernatural order. Get a beehive, if you don’t believe me.

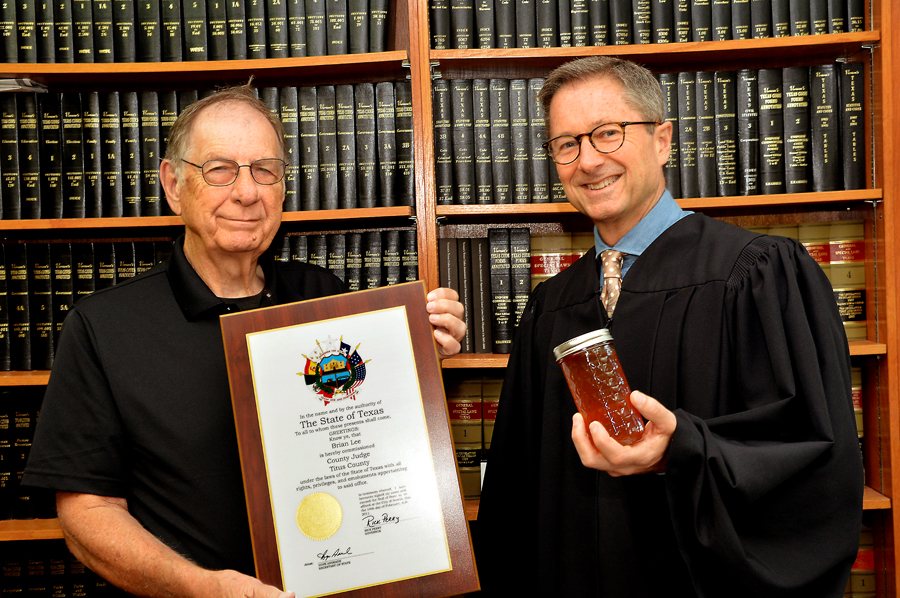

When Clare responded to my email and invited me to visit Buckfast Abbey, I asked Jesse Wright to go because he lives so close to knowing what can’t be understood. Fifty years ago, Jesse guided his Paul Pewitt football coach to a bee tree in a Morris County creek bottom. The teacher showed him how to use smoke like magic and transfer the colony to a beekeeper’s hive.

That was all it took. Half a century later Jesse’s still bottling Boggy Creek Honey. He’s the recognized guru of the Caddo Trace Beekeeper’s Association. We need him more than he needs us.

Bees and Buckfast Abbey go back into the mist of a thousand years, the founding of a Benedictine Monastery in 1018. In 1147, the monks began building with stone, creating spaces between walls where evidence of bees has been found.

The most notable interruption in the ups and downs of a thousand year tale of Buckfast Abbey has to be the part where Henry the VIII dissolved the Catholic Church in England so he could write new church rules greasing the skids for a divorce so he could marry Ann Boleyn. He also threw all the monks out of their monasteries.

Three years later, he opted to have Ann Boleyn beheaded rather than playing his divorce card again. Maybe he was avoiding a sizeable settlement. When he threw out the Catholics, the legend is he confiscated two and a half tons of the church’s gold and silver.

I was touched by a grave in the road we found near the abbey, that of a young girl who worked in a tavern. Being unmarried, she’d hanged herself when she found she was pregnant and because she’d taken her own life she couldn’t be buried in the church cemetery when protocol was strict concerning such things.

So she was buried in the road, intended for eternal degradation. Instead, more loving souls erected a marker, diverting traffic around the grave of a documented double sinner.

Thank God for forgiveness.

The Benedictine Monks named their order for Saint Benedict, a priest who wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict, a book of precepts the monks sum up in a word describing the work of the spirit of God – Peace.

Want some?

It’s different for bees given but a single season of life. Rather than centered on the individual, the divisions of labor within the hive come together as a singular drive to perpetuate the life of the hive.

The energy of the hive comes from the soil that nurtures all that blooms and provides raw materials for the magic of manufacturing stores of honey.

A chemical analysis of the honey from my nine hives identified two percent presence of pollen from cannabis (marijuana) the scouting bees found somewhere in the 80,000 acre range of worker flight. (No, it doesn’t get you stoned. Don’t ask if you don’t want to hear further chemical analysis of the intricacies of busy bee work processes related to pollen and nectar used in the factory.)

If everybody understood 1) the dependence of agriculture on bees pollinating crops and 2) the potential bees create from even the tiniest of blooms and 3) how many hives pollinating crops across America are brought to East Texas to winter, 4) nobody would mow until after the spring honey flow, after the bloom has passed.

Cut from the same cloth as Jesse Wright, just a half century earlier, Brother Adam got it.

I know because we found it, though certainly not from the photographs in his books showing the rank and file lines of the hives he worked on the windswept moor above the course of The River Dart streaming through South Devon.

That’s English. If they were Texans, they’d call it the Dart River. They also say “Dartmoor.” A “moor” is a tract of open, uncultivated land, a wild place such as Dartmoor on The River Dart.

In general terms, South Devon is 30 degrees cooler than East Texas. Add wind chill. And frequent rain. Bees don’t work in the rain. The cold does them no good. Dartmoor is a lousy place for bees, which demonstrates Brother Adam’s genius in picking the site for his work.

In controlling the genetics of bees breeding in the wild, he picked a place where the bees he brought would be the only contributors to a gene pool. No hive on its own would have picked the place for a permanent home.

Timing was critical. He took his bees there only during the time for the swarm, the breeding accomplished when the weather moderated enough for his bees to prosper.

We came upon skeletal remains during our search for his apiary.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Looks like it used to be a sheep,” Jesse said.

In our search for Brother Adam, other than skeletal remains we’d have found nothing of interest but for our guide, Martin Hahn. He’s a government bee inspector who moonlights a day a week in Clare Densley’s Buckfast Bee Education department. We trespassed. The abbey has sold off some of the land where Brother Adam kept bees. We ultimately found that the beekeepers who moved in to take over operations on the moor were less committed.

Clare’s purpose, as defined by the monks, is education, encouraging the work and development of aspiring communities of beekeepers.

The abbey no longer concerns itself with honey production. They have French wine grapes. They don’t need candles. Mead is out of vogue. Caffeine-laced wine is in.

It was Martin who found a metal post where Brother Adam long ago had mounted one of his hives. Where once was a meadow, the moor is overgrown. Nearby, we found his apiary shack, a storage room where he kept his supplies, a structure slowly and naturally dissolving.

It was Brother Adam’s development of the Buckfast Bee that saved Europe’s bees with queens passing to their hives an immunity to the Isle of Wight Disease.

That’s it.

No statues, no monuments, no annual celebrations, nothing much left beyond Brother

Adam’s three books, a void empty as wind sweeping over the moor, a passing quiet and unseen, a sense of solitude.

Peace.

Our three-hour cruise back to London shattered our previous record of seven and a half hours.