Salvage milks the most from the work of a forgotten builder

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal May 2020 Edition

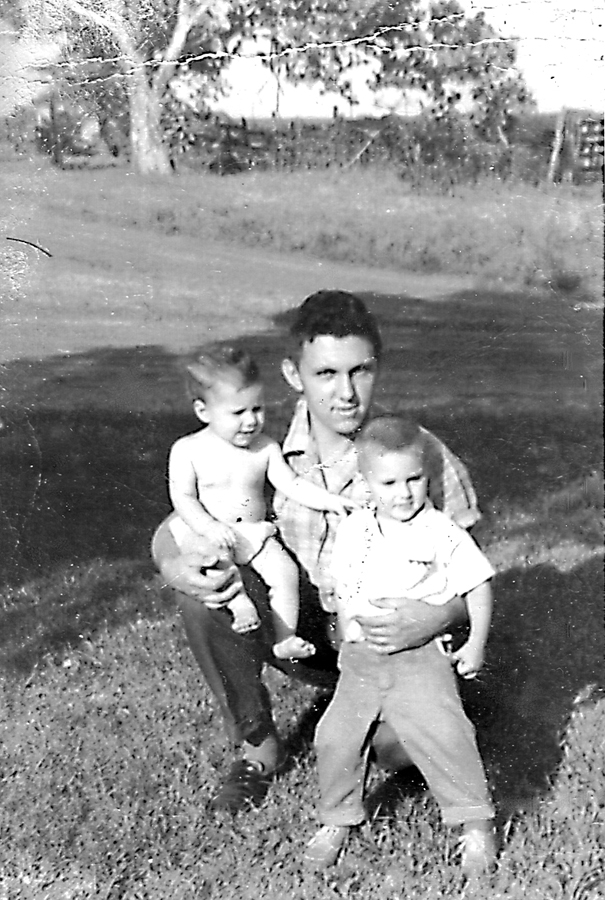

BRIDGES CHAPEL, TEXAS — When Lisa Garrison-Toland was a girl, “Grandma” Garrison’s place on Mason’s Hill was where you could find crawdads in the bar ditch on the short walk to the church and cemetery where Bernice Garrison was buried at 99, after Lisa was grown.

It was where she arrived as a young wife in 1947 and where in an instant she was changed to a widowed mother of four six years later.

“They came and got me out of school,” said Felix Henry “Sonny” Garrison, a surviving son. “He got up, went to work, came home not feeling good and three hours later he was gone.”

An oilfield man back in Cass County, William Dinton (sic) Garrison worked his way from there to Mississippi. Lured to Titus County by the promise of steady work as far as anybody could see in the wake of the 1936 oil boom, he moved the family moved to Talco with the Talco Pipeline Company.

“They built the pipeline to the refinery in Mt. Pleasant,” Mr. Garrison said. “They moved daddy to the pump station at Ripley.”

He was 8 the year the family mustered means to buy land from the Masons and move into a home built of hand hewn logs at some time forgotten.

In the eyes of a child, it was a castle.

“There were 12 foot ceilings,” he said. “I could stand up in the attic and walk on the rafters.”

Mesh tacked to hand-hewn walls was covered smooth with wall paper. There was a brick hearth, a detached kitchen in back where his mother could cook in summer without heating the house. The ceiling was beaded wood.

It was forever a work in progress with height enough to put a good slope on a shed walled into a room on the north side.

“Daddy made two rooms out of it,” he said. “We put a bed in the corner of the big room, another in a little hallway and a third in the back room for me and my brother – girls in front, boys in the back, mom and dad in the middle.”

Water was drawn from an outside well. Chores included outhouse maintenance requiring lime as a staple. There was no electricity and nobody made note of it.

“It was the same for everybody in the country,” he said.

They bought garden seed and staples at Charlie Fussell’s Store.

Cutting and splitting firewood and stove wood slowed when they got a butane tank, a butane cook stove, a butane heater “and a butane refrigerator,” he said. Refrigeration changed grocery shopping. People canned less meat and had more fresh.

Butane refrigeration was the beginning of the end for Duncan Baker’s ice truck. He gave up delivering ice for ice boxes, cut a contract with the county school superintendent and converted his ice truck to a school bus with benches where he’d once stacked 50-pound ice blocks.

“If you lived more than two miles from the school, you could ride the bus,” Mr. Garrison said.

They lived within walking distance of Stonewall, one of 30 “common” school districts “administered by local boards of three,” Rufus Bolger wrote in his 1942 Master’s Thesis, work on file in the University of Texas library.

Local boards were advised by an elected County School Superintendent answering to a County board of five members. In the management of education in 1947, that boiled down to a staff of two teachers and a cook for grades one through eight at Stonewall. During warm months at the cafeteria, they sometimes boiled water collected in a cistern, common practice for killing “wigglers.”

Compared to education in Talco, “that was a switch,” he said.

With 15 percent of the county school population and an oil-rich 55 percent of the county’s property tax value, Talco’s school was a facility second to none. Established in 1925 as an Independent School District accountable only to its local board, enrollment at Talco soared from 187 to nearly 800 when the Garrisons arrived in the oil boom era.

Transferring after the Christmas of 47, “I was one of five students on the third grade row my first day at Stonewall,” Mr. Garrison said. “One room was for grades one to four and the other was for five through eight. Each grade had its own row.”

Common School terms varied from seven to nine months. Average teacher pay was $837 a year.

He’d graduated Stonewall and was riding a bus every day to high school in Mt. Pleasant the day life changed.

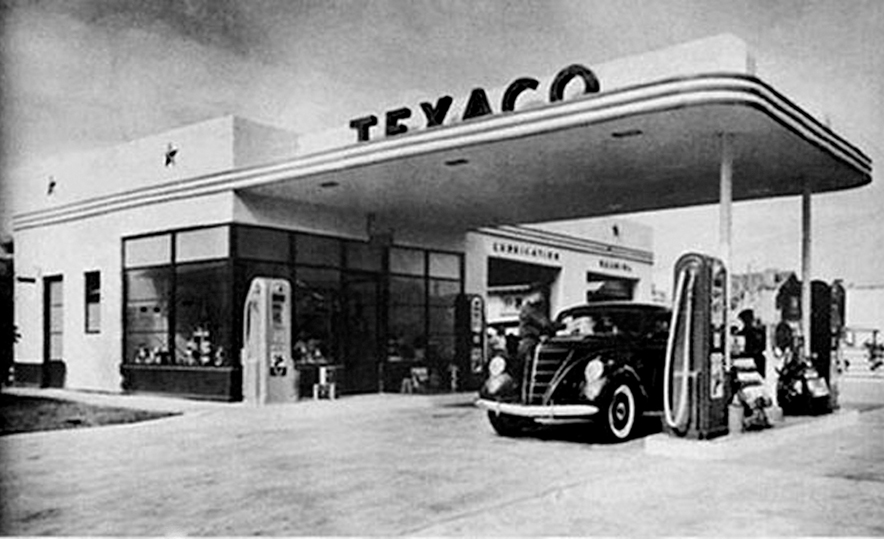

“I went to work after daddy died,” he said. Summer days he hauled hay and evenings he pumped gas and fixed flats at Gene Gaddis Texaco, a part of the Gaddis Hotel complex on U.S. 67, the east-west highway from Texarkana through Dallas to points west.

Palms were part of landscaping around the hotel’s Olympic-sized pool. People tanning on chaise lounges was a foreign concept at Mason’s Hill.

Night life was lively across the highway at the Dairy Queen and the A&W Root Beer Stand, early franchises.

Four years later, he enlisted in the military.

“My first time on an airplane I was aboard a late afternoon flight with a company of Texas boys flying out for basic training in California,” he said. It was exciting stuff.

“The night before we caught the train to the flight out of Dallas, four of us got a car and drove to Shreveport to go to the Grand Ole Opry,” he said.

He couldn’t remember who performed, seeming to say he’d have thought more of it, seen those days in a different light if he’d known then he’d never go back to Mason’s Hill.

As told by Jimmy Mason, Mason’s Hardware, after the Civil War William Varney Mason brought the family name to Titus County when he walked here from Georgia.

He put together land over time and made a director of the Merchants and Planters bank in Mt. Pleasant, the first to roll belly up in the cotton depression of the 20’s, a time before 1933 “New Deal” legislation insured deposits.

“They put up their land as collateral and borrowed to pay off the depositors,” said Mr. Mason, the son of businessman and once County Judge John Mason.

After William Varney died, the Mason family Christmas tradition included passing the hat with each contributing as they might to pay off the note.

“Only took three generations,” Jimmy remembers John Mason’s line, one delivered as a lesson in guiding principles.

“You take care of your family name,” Jimmy Mason said.

Mr. Garrison remembers the family he figures built the cabin at Mason’s Hill as business people and educators in the 40’s.

Henry Mason, he said, went with the Blackburn Syrup family that had established the family enterprise in Titus County before building bigger in Jefferson.

“One of them had a hardware store in Mt. Pleasant,” he said. “One of my teachers at Stonewall, Earnestine McAffey, was a Mason.”

After the service, Mr. Garrison hired on as an electrician’s helper at Lone Star Steel.

“I made an electrician and followed that trade the rest of my working life after I left Lone Star,” he said. “The way it was there, you’d work a while and get laid off a while.”

Long abandoned, it was the solid lengths of hand hewn timber at the Garrison place that tantalized Marty Bell, who bought land in the community before retiring from the Mt. Pleasant Lowes store.

“It’s old growth, slow growth oak with tighter rings,” he said, not the kind of timber commonly sawed in mass production mills now. “It’s denser, heavier, beautiful stuff for wood working,” Marty Bell said.

The chimney was built with fire brick rising from a foundation of rough-fitted native stone.

The place had passed on to Lisa, whose memories of Grandma Bernice’s home included her adolescent tom-boy days catching crawdads.

It was the value Marty Bell found in the place that made it easier to agree to take it down in a way salvaging something old to make something new.

A licensed officer, she works security at Northeast Texas Community College, which was where I rolled down the window to visit on a Saturday afternoon I took a slow detour through the campus to admire the newly painted Whatley Center for the Performing Arts, a job left begging too long.

“I’ve got a story you’ll like,” she said. “He doesn’t know he wants to talk to you yet, but you need to call my dad.”