Dietary atrocities endured aboard war’s busiest carrier

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal May 2016 edition.

The development of powdered milk and dehydrated potatoes were considered wartime atrocities by sailors aboard the USS Natoma Bay (CVE 62). They ate so many Australian goats they bleated at each other by way of greeting.

“The USS Natoma Bay was the most uncomfortable ship in the whole U.S. Navy,” wrote Navy Historian John Sassano.

Living space was a premium. Do the math: bunks two feet wide and six feet long were stacked four high under a ceiling coming in at just under eight feet.

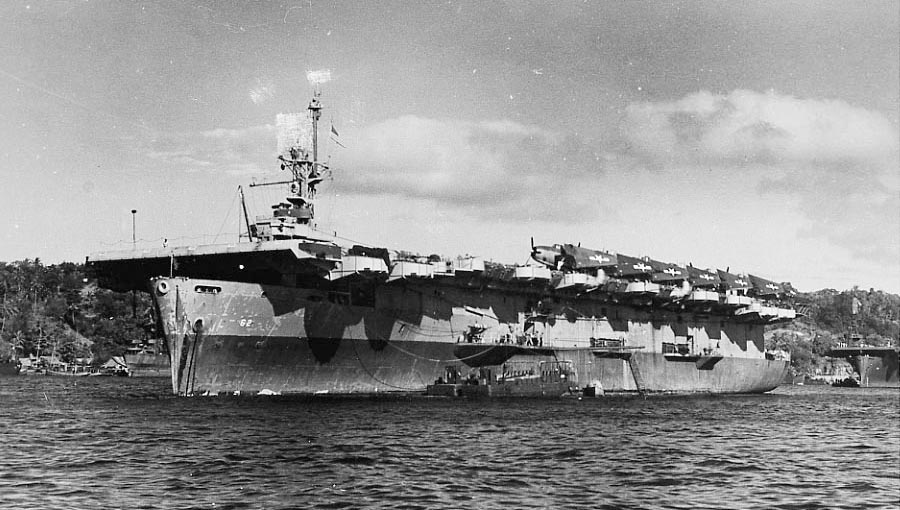

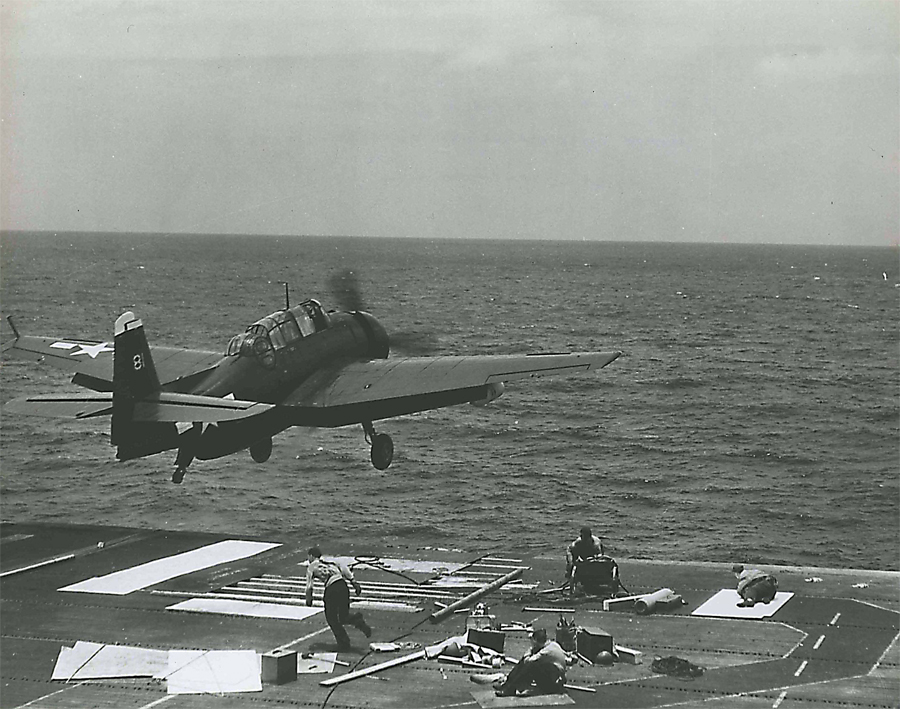

The big brains in Detroit and Washington came up with the idea of fleets of “postage stamp” aircraft carriers. Car builder Henry Kaiser envisioned building a fleet of small carriers by converting hulls designed as merchant ships to floating air strips from which catapults could launch planes.

Coming in was another matter.

“Our pilots said it was like trying to land on a postage stamp,” said J.D. Baumgardner. At 18 he volunteered for the Navy to keep from being drafted into the army infantry, thinking he’d be shot at less at sea.

This plan did not work.

Nor did the original concept of the “Long Island” class of carriers as escort and transport ships ferrying planes precede as planned.

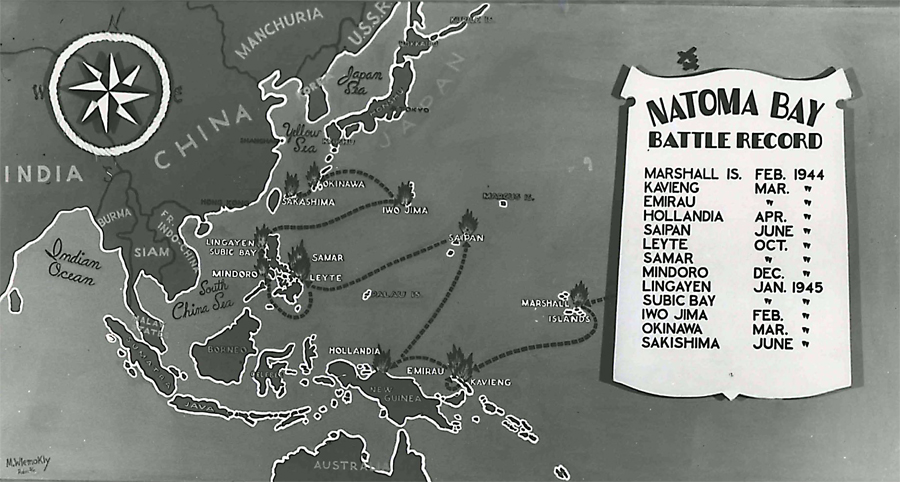

From the day she was christened and set sail from the American west coast until the end of the war, Mr. Baumgardner was aboard the boat that took part in more operations than any other ship in World War II.

After the Japanese sank America’s first two premier carriers, the Lexington and the Yorktown, the “Kaiser Coffins” were pressed into battle. Hull design afforded the ships a top speed calculated at 17.4 knots. With the Japanese fleets chasing them running at 25 knots, the crew of 785 sailors and 185 officers aboard the USS

Natoma Bay learned to milk 19 knots out of her. Everybody felt better about that until the day after they rode out their third typhoon while trying to get into Leyte Bay.

The storm delayed the advance and had prolonged what became the biggest battle in the history of the American Navy. Originally, everybody instinctively knew that the critical moment would be passing through a straight six miles wide with Japanese shore guns able to reach them from either side.

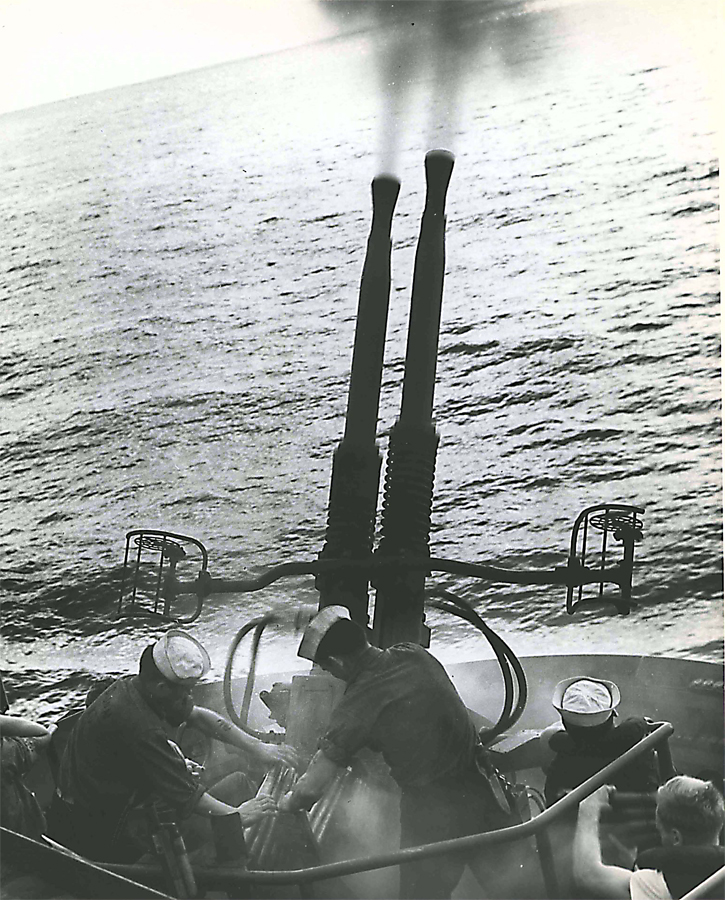

It was spookier when in the midst of a third consecutive day of non stop fighting the crew realized that at the rate they were firing their guns they were going to run out of ordnance – not to mention food and fresh water. The magnitude of the Japanese defenses turned the mission of the pilots of the Natoma Bay’s 18 fighter planes. Rather than escorting bombers on shoreline runs, they were pressed into dogfights defending their ship – a place to land was a priority.

Then there was the typhoon, then there was the next day. Down in the radar room, radio operator Baumgardner’s job was living through his headset, plotting locations and movement of ships streaming in, tracking the battle. So he was among the first to recognize the battle formation taking shape and bearing down on his ship while knowing they didn’t have the ammunition to put up a fight.

They turned out to sea and ran. That 19 knots wasn’t enough.

“That’s the only day I remember being scared,” Mr. Baumgardner said. “We were dead ducks.”

Strangely, whatever happened – their pursuit had all but closed to range for her big guns, then turned and sailed away to some more urgent battle call.

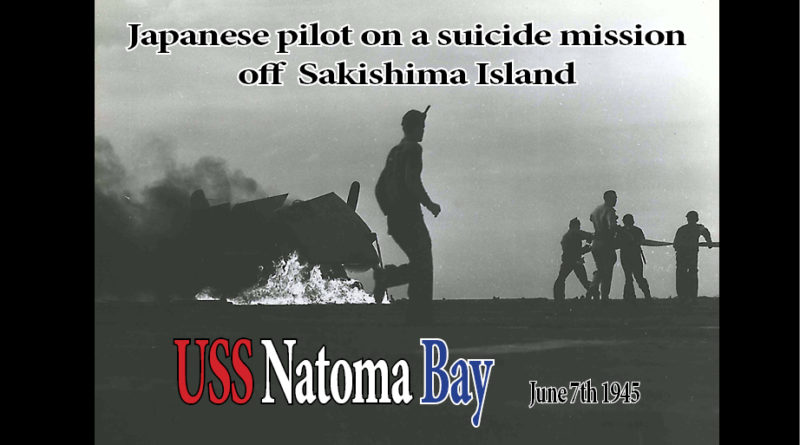

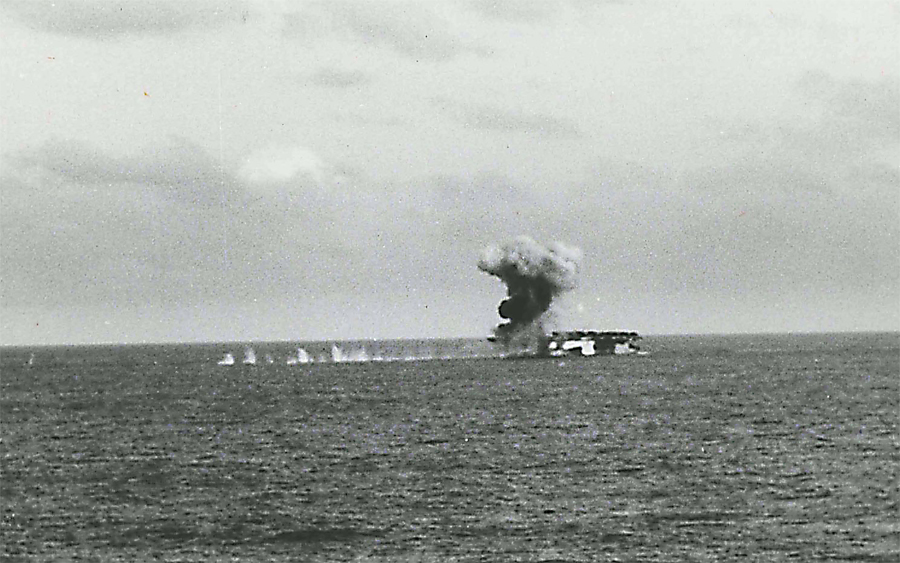

The Japanese pilot on a suicide mission who one afternoon nose-dived into the USS Natoma Bay put a 40-foot hole through the 65-foot wide flight deck before going over the side.

“I remember I was eating an apple, then all of the sudden our guys were swarming up like ants. We had repairs made and were launching pilots in four hours,” he said. In his diary, he made note of a burial at sea for the one sailor who died that day, a solitary thing that must have touched him. He’d just turned 20 and after two years at sea, he’d seen a lot worse than that.

Another oddity – Japanese prisoners were rarely taken at sea. Along with the diary he kept, which was a court martial offense, he saved a leaflet telling the story of a Japanese pilot trained in the tradition of a Samaria. He was captured after being shot down and being adrift for days. He said if he survived to get back home, his father would provide him the knife with which he would be expected to commit ritual suicide, regaining in death the honor he’d lost by being captured.

Mr. Baumgardner made his diary entries daily. Other than occasionally bleating at the cooks when served another helping of goat, his only offense as a sailor was keeping a nutshell record of his days at sea. The poignant entries are written without flare, without drama, numerical reports of ships, planes or men lost and the same for casualties inflicted.

He wrote of celebrating Christmas once with boxing matches.

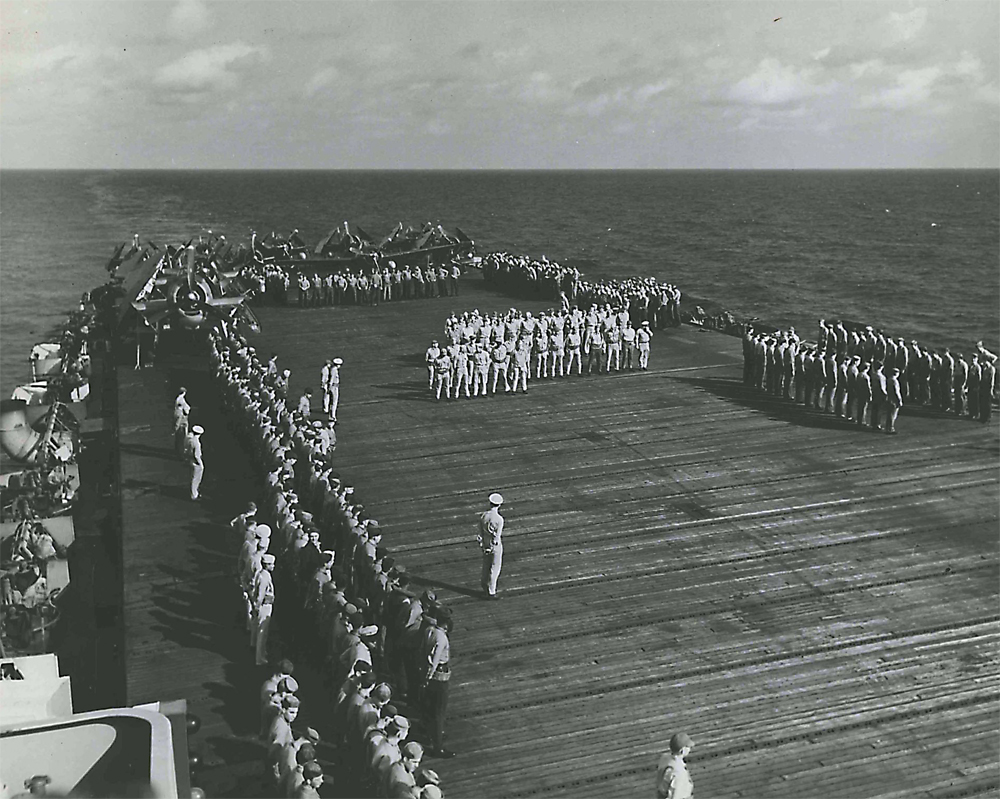

The Presidential Unit Citation awarded the USS Natoma Bay cites “heroism” in duty, cites “losses to the enemy in warships, aircraft, merchant shipping and shore installations,” makes note of its assuming the role of flagship in the Battle for Leyte Gulf where she “fought her guns gallantly against enemy dive bomber and suicide planes,” as well as the day her pilots flew “55 missions from her flight deck after being hit by a Kamikaze in the assault on Miayko Jima.”

She was at Iwo Jima as well. She was in 14 naval engagements as was awarded eight battle stars.

“The USS Natoma Bay wore out three admirals, four captains, three squadrons, and took part in the greatest sea battle of all time,” John Sassano wrote.

The men in the ship’s shop who’d coordinated repairs at sea salvaged the prop of the plane that went through the deck, melted it down and made miniature horse shoes for every sailor aboard that day.

It was June, 1945, and worn by service after the battle at Miayko Jima the USS Natoma Bay was ordered back to Pearl Harbor to have its flight deck replaced. The work was completed in July in preparation for an anticipated attack on the Japanese mainland.

In early August, the Japanese surrendered after two atomic bombs were dropped and the USS Natoma Bay’s war was over.

Seventy five years have passed but Mr. Baumgardner can cut back through them to the day it began.

“It was June 11, the year I was 18,” he said, “when I went for my physical. “I was told that if I was warm, I was in.”