Cookville business boom fueled five newspapers

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal January 2019 Edition.

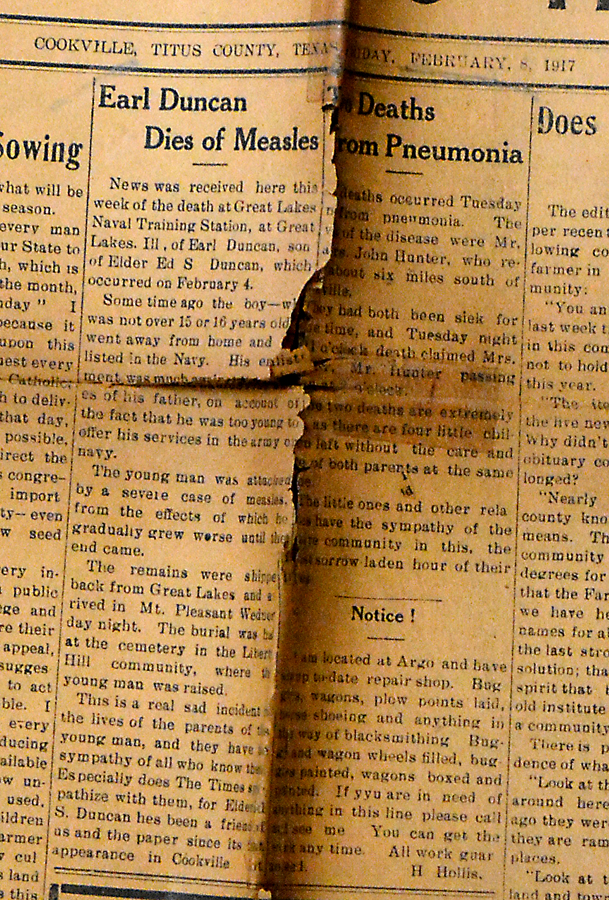

COOKVILLE, TEXAS – With World War I in full swing, Earl Dunkan left here for the Navy. He was 15 when he was brought home to be buried. One of five newspapers spanning the rise and fall of a farm town, the February 8, 1917 Cookville Times reported that he’d died of measles at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station.

Locally, there were two deaths from pneumonia.

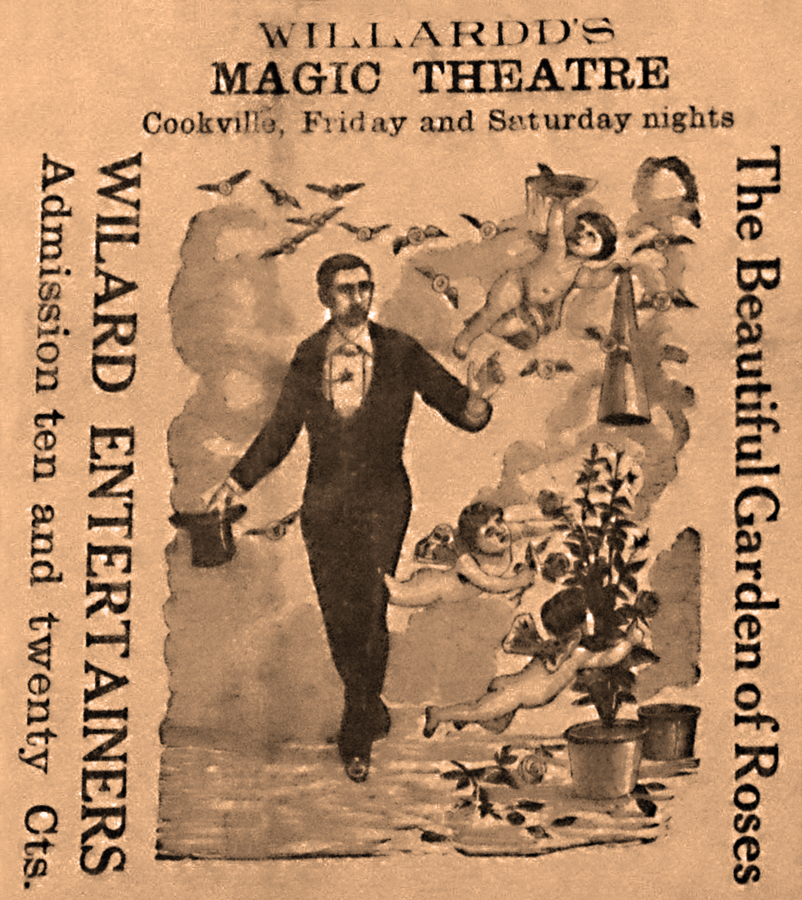

Described in the modern-day Blog “Magic Detective” as “the best musician of the 20th century,” the newspaper announced a two-night performance by “Willard the Wizard.”

An Irishman who traveled America, one of his greatest illusions involved strapping an assistant to the mouth of a cannon.

“When it went off, she vanished in a cloud of smoke. And of course, she was discovered moments later in a nest of boxes across the stage.”

B.B. Stevens Mercantile Implement Company ran a half page ad trying to collect accounts.

“We have went beyond our judgment in selling on credit, but our good friends were so badly in need of help that we thought if it was in our customer’s interest to strain ourselves to help them, then they would surely appreciate the favor enough to strain as hard to pay us,” it says before describing vendors now calling the store’s accounts due. “Therefore, we are forced to ask and demand that all parties owing us notes and accounts make arrangements to pay during this month.”

Telephones had arrived. Cookville Telephone Company proprietor J.W. Covey advertised that his switchboard would take all calls from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. and calls for doctors around the clock.

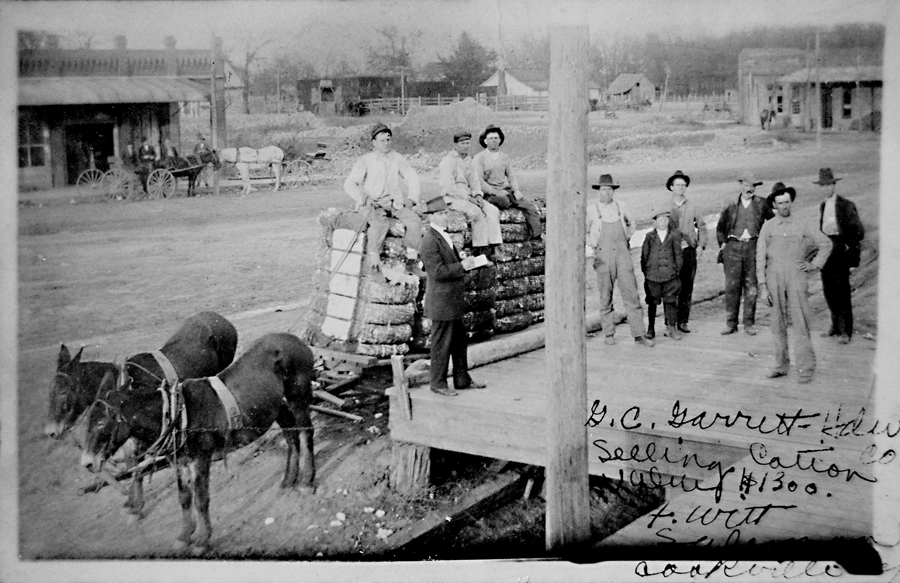

The February edition of the Times is one of two we’ve found, both mailed to G.C. Garrett’s store, one of seven hardware, farm implement and general merchandise stores here when H.P. Burford arrived in 1883.

“One of the main items of merchandise was high top boots and salmon, sardines and oysters, fat bacon, flour, sugar and coffee – in other words, frontier stuff,” Mr. Burford wrote. “When a man came into town he would buy him some salmon, sardines or oysters the merchant cut up in a bowl and served with pepper sauce and crackers.”

Crackers were packed in 20-pound boxes.

“Rats could get in the cracker box, but nobody bothered about that,” he said.

In 1917, 1,000 Americans were lost with the sinking of a British Troop Ship. In France, American troops had driven the German’s back at the “Lorraine Front,” a region in dispute since being annexed by Germany with the close of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

The war in Europe created a war-time economy that reached Cookville.

“Use of the most improved farm machinery is of special importance now,” said the ad for G.C. Garrett’s business, citing “the latest bulletin from Uncle Sam to his farm fighters,” as his source. “Right on your firing line, we take care of your implement needs.”

In January, 1917, Palace Drug invited customers to its “Sanitary Soft Drink Fountain” and S.B. Nichols opened a restaurant serving fresh meat. Jno. Bevill merited a front page ad with his offer to pay “$50 for the name of the thief that stole my dog, plus $5 for the return of the dog, a 3-year-old hound.”

The son of a Georgia lawyer who’d given up his practice for the pulpit, Andrew Barney Cook was celebrated as a Confederate hero before arriving in 1867 at the community later named for him.

Once wounded and twice a prisoner of war, “In the death dealing battle at Iuka (sic) two brothers older than himself of Whitefields Legion had been color bearers, each falling successively before Major Cook grasped the bloodstained banner from the prostrate forms of his wounded brothers and bore it aloft to a glorious victory,” read the Mt. Pleasant Times Review account of his passing November 13, 1902.

“His father came to Texas in 1848 and purchased land in the Northern portion of the county and on his way home for Christmas and to bring the family to Texas he was drowned while crossing Red River on horseback,” Major Cook’s son, Reuben, wrote in 1963. “But his wife came on, with the family, in 1851.”

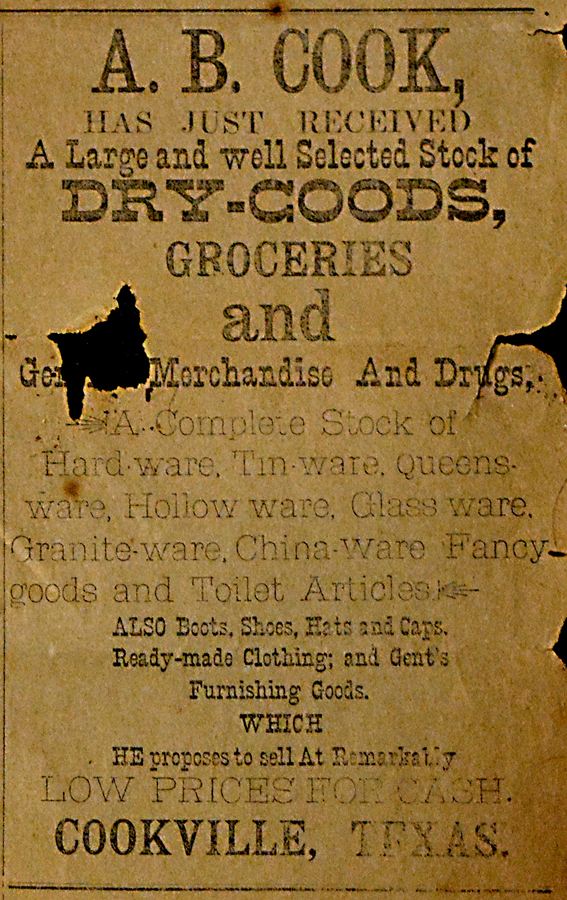

In the November 26, 1890 edition of The Cookville Banner, Major Cook announced the arrival of a “large and well-selected stock of Dry Goods, Groceries, General Merchandise and Drugs.” He stocked “Hardware, Tin-ware, Queensware, Glassware, Granite-ware, China-ware, Fancy goods and toilet articles” along with “Ready Made clothing Which He proposes to sell at Remarkably Low Prices for Cash.”

Other newspapers published in Cookville included The Cookville Magnet, the Wide Awake and The Herald.

In the 1890s, Cookville had “one of the best schools in the County,” Richard Loyall Jurney wrote in his History of Titus County Texas, 1846 – 1960.

A cotton buyer, an investor, a businessman and a story teller, in 1904 H.P. Burford was made the first cashier and later became a 40 percent owner and President of the State Bank of Cookville. Chartered by Mt. Pleasant businessman Morris Lilienstern, in Mr. Burford’s account the bank scraped by in 1905 and 1906, but without any real concerns.

“Our stockholders were worth about a quarter million dollars, which made the bank safe enough, if you considered that we didn’t have but about $10,000 in deposits,” he wrote.

“The day before the panic of 1907 hit, we had a lot of cotton on hand and we sold that so that would fix us to where we could take care of our customers. We never did shut down. Anybody wanted his money, we let him have it.

“We paid a dividend every year from 1906 to 1920.”

At the height of it, the cotton gin put up 5,000 bales one year, Mr. Burford wrote.

“We run the deposits up there about $150,000 – we thought that was lots of money then, but it wouldn’t be a drop in the bucket the way it is around now.”

It was 1920 that marked the beginning of the end of the cotton economy that had been the backbone of the Old South. With the end of World War I, the demand plummeted. Having all the uniforms needed for peace time, Uncle Sam quit buying cotton.

At the high point of the market, cotton sold for between 37 and 42 cents a pound in April, 1920.

“Cotton was high priced the first of the year,” Mr. Burford wrote. “Then the Federal Reserve Bank started to deflate and they couldn’t keep their mouth shut about the deplorable conditions of the cotton farmers. They run cotton down to 8 cents in a short time. Busted all our customers and us, too.”

Cookville changed.

“One fellow drove up to the bank one day and told me to come out and he would show me something,” Mr. Burford wrote. “He had a stripped down Ford with a wagon sheet over the back. He just raised that and he had it stacked full of wildcat whisky.

“After the war, and after the cotton depression came, lot of the people went to making liquor and they made lots of it. Looked like they might move one corner of the Federal Reserve out there. You take a lot of farmers that never made any money much – make five bales of cotton, get around $250 to $500 for the year – go out there and put up a lot of liquor and make $250 to $500 in a month or two.

“My father had bought Major Cook out. When the bottom dropped out of cotton he couldn’t collect on his accounts, you know, so he closed up.

“The bank closed in 1921 and the businesses started moving out. Moved onward to Morris County over at Omaha, some to Mt. Pleasant. The brick store buildings – they tore them down for the brick. They had 16 there, all gone.”