Steel company executive turns tide to LBJ at the unconventional Democratic convention of ’64

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal June 2013 Edition.

Ed’s note: An ex-Marine who got into Texas politics following World War II, Marvin Watson served as head of the Texas Democratic Party before moving to Daingerfield and going to work at Lone Star Steel. He’d worked for Lyndon Johnson during a 1948 senate race. After Johnson was elected, Watson turned down repeated offers to join the senator’s staff.

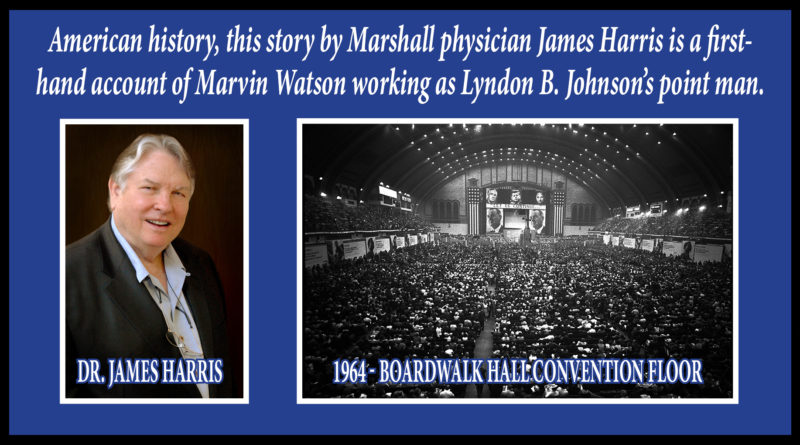

After LBJ ascended to the presidency with the assassination of John Kennedy, in the summer of 1964 Johnson called on him again in the days before the Democratic Convention. Though Watson is little more than a footnote in American history, this story by Marshall physician James Harris is a first-hand account of Watson working as Johnson’s point man, taking control of the convention and thwarting the carefully crafted plans of Kennedy-family loyalists.

By JAMES HARRIS, M.D.

Special to The Journal

In August, 1964, in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the Democratic Party staged a convention that, even for a political party in the midst of leadership and philosophical changes was most unconventional.

To a 22-year-old medical student the convention provided a close-up view of diverse and fascinating people and events posed then on a convention-hall stage and remembered now on the stage of history.

My father was a pediatrician in Marshall and one of his patients had once been the very sick son of Marvin Watson, the executive assistant to Lone Star Steel President E.B. Germany.

The Watson child survived and Watson formed a close and grateful friendship with my father.

When President John F. Kennedy was murdered in November, 1963, Lyndon Johnson inherited a presidency and a bureaucracy staffed by people loyal to the late president and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. They ran the Democratic National Committee and had already picked Atlantic City as the site of the 1964 convention.

Johnson asked Marvin Watson to go to Atlantic City to evaluate the preparations. In his book Chief of Staff: Lyndon Johnson and His Presidency, Watson describes finding that Robert Kennedy and John Bailey, head of the Democratic National Committee, had arranged to completely control the convention including the seating of delegates, the program, the speakers, the housing and the social life. Watson wrote that Kennedy supporters planned to manipulate the convention in order to nominate Kennedy rather than Johnson for president.

When Watson reported the situation, President Johnson convinced Watson, who wasn’t even on the payroll at the time, to return to Atlantic City and take over preparations for the convention.

I was to begin medical school in the fall of 1964 and planned to do some traveling during the summer, including a visit to the New York World’s Fair. Watson and my father arranged for me to also spend a week working at the convention.

When I was put in charge of the page service I didn’t know I was going to be supervising a covey of boys, many related to the Kennedy people.

I was fortunate in that one of Watson’s sons, Lee, was also involved. He would have made a good head of the service because he knew everyone important. He was only 18, but he had a pleasant swagger and a wonderful personality. Recognizing that my being put in charge was simply a matter of my being older, we split the leadership, the hours and the headaches and became fast friends.

The pages were mostly Yankee city boys and many were too young and immature to be trusted with some of the sensitive assignments we were called on to handle.

After a couple of days we knew pretty much which ones we could trust to handle various tasks, comprised mostly of making deliveries in the convention hall. Thankfully, we had no responsibility for the pages after working hours.

The best page we had was a mature and intelligent blond-headed boy from Dallas named Harlan Crow. He was about 15, maybe younger. I tried to save him for the most important work, especially after one of the Kennedy band of boys left some papers related to arrangements for President Johnson’s birthday party on the last day of the convention on a bench on the boardwalk.

The convention was over before I found out that Harlan Crow’s father was the legendary developer, Trammel Crow.

One of my most poignant memories was meeting a fellow named Walter Cronkite who taught me about scotch at a party the night before the convention opened. I was able to go because of passes Lee Watson got us from a tall red-haired boy from Texarkana whose dad was wealthy. He had a pocket full of top social passes, the ones reserved for big donors.

Having been investigated and cleared by the FBI, we had the even more important security passes clearing us to go anywhere, and we did, with our passes swinging like priceless jewelry around our necks.

After shutting down the page service at 6 p.m. we’d take off and forage first for something to eat since our boarding house was a couple of miles away down the Boardwalk, too far to walk for a meal.

I’d been broke for days, living on hot dogs I was able to afford after my brother wired me some emergency cash.

I met Mr. Cronkite at Judge Tom Conally’s birthday party. He was a Texas politician, a distant relative of John Conally. When I spied my favorite newsman, I joined him at a window seat close to the bar. I was a gangly, young nobody but he was nice to me. When he found out I was also a Texan, he taught me that scotch whiskey was a refined drink, more likely to reflect gentility and to prolong sobriety, as opposed to the national drink of East Texas, bourbon and coke.

I was pleased to be his gofer.

Unconventionally, Cronkite was not the CBS anchorman at that convention, as he was at every other national convention from 1952 until he retired in 1981.

NBC’s Huntley and Brinkley had dominated the ratings at the Republican Convention in July so at the Democratic Convention the CBS brass replaced Cronkite with Roger Mudd and Robert Trout as co-anchors. NBC beat CBS again in the ratings and four years later Cronkite was reinstalled as the CBS anchor.

1964 marked the end of the New Deal coalition of democrats with the splintering away of the conservative white Southerners who ultimately landed in the waiting arms of the Republican Party and Richard Nixon in 1968.

Johnson himself had speculated on that result when he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 just before the convention.

The height of racial unrest that summer was in Mississippi where political activists were working to register black voters.

On June 16 two white boys from New York and a black civil rights worker were murdered by Ku Klux Klan members, some of whom were lawmen from Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Mississippi Freedom Delegation Party (MFDP) was formed. They chartered busses for the trip to Atlantic City.

News accounts told of their numbers being in the thousands. I saw only a few hundred at any one time, picketing on the Boardwalk.

Johnson had championed their cause when he signed the Civil Rights Act and his forces at the convention were determined to avoid confrontations. Unconventionally for 1964, the Credentials Committee granted a hearing requested by the MFDP delegation bent on unseating the regular Mississippi delegation, largely made up of segregationists.

When there were only three television networks, all three televised the hearings, which were held on an otherwise quiet afternoon. I attended.

Having the run of the convention, I was by this time pretty much taken with myself. I wound up sitting in the box with those who were set to testify. One, a middle-aged man sitting to my left, ran out of cigarettes and started bumming from me. He looked familiar; I realized Mayor Richard Wagner of New York City was smoking my cigarettes.

He was said to have vice presidential aspirations. It was hot in the room and he had on a suit and tie and sweated considerably.

I heard the now-famous testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer, who talked about the murder of Medgar Evers in 1963. She also described how she was beaten when she tried to register to vote in Mississippi.

I remember a tragic Jewish lady named Schwerner, the young widow of one of the dead civil rights worker whose body had been found in an earthen dam in Mississippi. Her despair was palpable and I will never forget her and her sad countenance.

Ultimately, the credentials committee made a deal to seat two of the MFDP delegation members in the balcony. It has been speculated, without documentation, that Hubert Humphrey was chosen as the Vice Presidential candidate as part of the mediation. Humphrey, Walter Reuther and several civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King and Roy Wilkins worked out the compromise.

Two days later, at the onset of the convention, all but three members of the Mississippi Delegation walked out after refusing to sign a loyalty oath to the Democratic Party.

After the televised hearing, the MFDP became old news, just as Watson and President Johnson had hoped.

Unconventionally, no roll call was ever held at the 64 convention. Johnson was nominated by acclamation so neither Mississippi delegation got to answer a roll call.

It didn’t take me long after the convention began to find that the best seats in the house were under the massive stage at the front of the convention hall. The same hidden space housed the White House offices. It was a wide hall with comfortable sofas and chairs. Speakers waiting to go up to the podium, secret service agents, various convention functionaries, Johnson cronies and I hung out there.

There I met the nicest person I remember, Phillip H. Hoff, the first Democratic governor from Vermont since 1854. He was a handsome fellow with an athletic build and a nicotine habit. Cigarettes brought us together. He invariably ran out and smoked mine.

He was being groomed for national attention and accordingly had been asked to wait until he could be worked into the program for a short speech that would be seen by millions of TV viewers.

His time never came so he and I sat together under the stage for three nights.

We sat just inside the door leading in from the convention hall where we had a view of three television sets through the door of the office of Walter Jenkins, then Johnson’s Chief of Staff.

Johnson’s forces dominated the convention.

When the Kennedy faction finally got a little TV time, it had been moved by Marvin Watson to a terrible late-night time slot late in the convention, after both the President and Vice President had been nominated.

That night, Governor Hoff and I were in our usual seats when Robert Kennedy came in. There were a number of speakers and a lot of President Johnson’s cronies in the room.

Robert Kennedy was a small man. He walked directly through us, ramrod straight, looking neither to the left nor the right. He didn’t smile. He didn’t say a word to anyone. Without stopping he climbed the stairs at the end of the hall leading up to the stage.

Once introduced to polite applause he made a short speech, then showed a film to honor his late brother. Both the speech and the film were well received and elicited thunderous applause.

He exited without a word or a glance at anyone. He was crying. He had not one single confederate there under the stage.

The convention that his folks had hoped to hijack was firmly in Johnson’s control, thanks to Marvin Watson.

George Wallace made an appearance earlier in the week. He was a small man, well dressed, surrounded by large Alabama highway patrolmen. He pranced around like a terrier for a few hours, then I never saw him again. He had run well in some of the Democratic primaries early in the year, but he had no real chance of securing the vice presidential nomination he was hoping for.

When he arrived, the MFDP was picketing outside the main doors. Peter, Paul and Mary, the famous liberal folk singing group, were holding court just inside the hall. Just out in the Atlantic was a Barry Goldwater sign that said, “In your heart, you know he’s right.” Someone had affixed another sign to it that said, “Yes, far right.”

One night I stepped into an elevator to find myself going up with Lady Bird Johnson and Frederick March, an actor and a well-known liberal. Ironically, the movie Seven Days in May, in which he played the President, was showing everywhere at the time.

I introduced myself and told Mrs. Johnson I was from Marshall, where she’d graduated from high school. She grew up in nearby Karnack.

She asked if Dr. Harris was my father and when I replied that he was, she said, “Please give him my warmest and fondest regards.”

I was more than a little impressed that she remembered him. What a gracious and charming lady she was.

In the November general elections, Johnson won by the then largest margin in history over Barry Goldwater and William E. Miller.

The convention was one of the high points of my youth. Looking back, it seems strange that I never saw Billy Don Moyers, from Marshall. He was one of Johnson’s closest operatives and speechwriters.

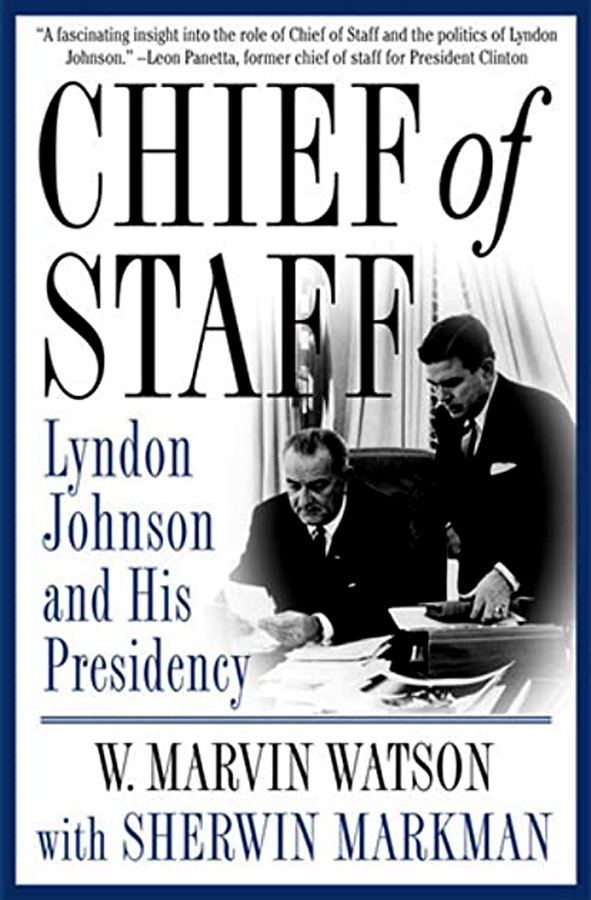

Chief of Staff. Others from left are President Lyndon Johnson, Press Secretary Bill

Moyers, Special Assistant Jack Valenti and speechwriter Horace Busby.

Nor did I see the Johnson daughters, with whom my younger brother and I had been paired for about ten minutes at some political function in Marshall several years before.

Wright Patman, Congressman from the First Congressional District of Texas from 1929 until 1976, a friend of my father’s and a devotee of my mother’s fried chicken, most likely was present but I didn’t see him either. It’s heady to say, but at the national convention, mere Congressmen don’t amount to much in the pecking order.

A few months later I saw Johnson again in Mt. Pleasant at a gathering at the local armory in honor of Marvin Watson, a man who that night Johnson described as “as wise as my father, as gentle as my mother, as loyal and dedicated and as close to my side as Lady Bird.”

Johnson had gone to considerable trouble to get there. He borrowed Governor Connally’s DC3 in order to land at the local airport described by the national media as a grass strip in a cow pasture, which wasn’t accurate. Mt. Pleasant had a perfectly fine asphalt paved strip long enough to squeeze in a slow-flying plane.

I saw him again once at a University of Texas football game.

But the last time I saw him was the most memorable. I was the doctor in attendance at his burial.

From 1971 to 1973 I was an internist in the Army Medical Corp stationed at Darnall Army Hospital at Fort Hood.

Periodically, consultants from Brook Army Medical Center and doctors from Austin who saw military and federal dependents would regale our doctors with stories about what a good guy but a terrible patient President Johnson had been. In a good-humored way they revealed that he smoked, drank and wouldn’t follow a diet. It all caught up with him and he died at his ranch at Stonewall on January 22, 1973. He was 64.

After funeral services in Washington at which Marvin Watson delivered the eulogy, he was flown back to Texas and bussed back to the family cemetery on his ranch along with Billy Graham, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the cabinet and what appeared to be about every legislator in Washington or Austin.

Knowing my family’s Johnson-family connections, my commanding officer had me take a MASH (portable) hospital to the graveyard. Actually, all I had to do was show up. The real soldiers put up the hospital.

It was alternately raining and sleeting that day. There was a long walk to the cemetery. Billy Graham preached too long for the weather and John Connally talked too long as well.

I remember Senator Edward Kennedy with his wife who was beautiful but obviously ill as she tottered along in high heels. She had trouble keeping up with her unsmiling husband as they walked in a long line of dignitaries down the narrow country road.

Periodically, mourners would slip into our hospital tent to warm up. It had a large stove. I went in once to check things out and recognized Price Daniel Jr., Speaker of the Texas House at the time. We’d met at American Legion Boys State. He and his wife were arguing loudly.

I didn’t say hidey.

The sleet got worse. I stood under a scraggly piece of a tree with a Secret Service agent. Having used my army uniform allotment to buy furniture, I was clothed in my only dress military apparel, a lightweight summer green uniform with a dinky folding hat.

At $50 used, the fancy army hat with the braid on the bill that, as a major, I was entitled to wear, was way out of my price range.

I was shivering intermittently and once while Billy Graham was speaking the Secret Service agent looked at me, fingered my $7 raincoat and said, “Doctor, you got to do better.”

In the years since, I have done some better and after many years of medical practice and ranching I am now retired with enough time for reflection about an unconventional and exciting time in August, 1964 and a courageous president who has not been given adequate acclaim for the noble and far-sighted legislation he enacted.

And especially, I remember again with fondness a decent and loyal man that history will ultimately forget, Marvin Watson.