Daingerfield resident changed course of American history in 1964 election

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal July 2016 Edition.

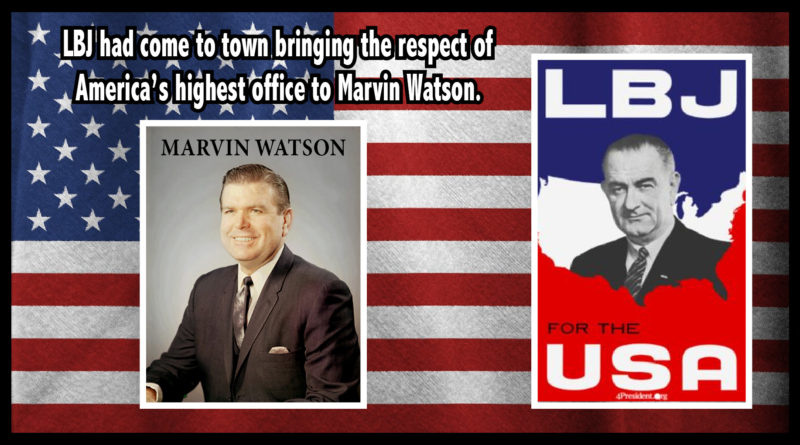

MT. PLEASANT, TEXAS – In the November 25, 1964 Mt. Pleasant Times, a double-deck banner headline declares LBJ had come to town bringing the respect of America’s highest office to Marvin Watson.

News accounts of the banquet that lured LBJ here to honor Mr. Watson are sketchy.

You can read three front page stories packed with details down to what America’s First Lady was wearing and never get more than clues about Marvin and Marion Watson, who were presented a punch bowl set that evening.

Playing to an overflow house pouring out the doors of the National Guard Armory, the President “sent the jammed crowd into gales of laughter,” Times Publisher W.N. Fury wrote under the sub-head, “Chief Executive Makes Unscheduled Visit.”

“I’ve become unaccustomed to public speaking since November 3 . . .” the president drolly delivered an opening line, bringing down the house “in his first public appearance since being elected to a full term in his own right on November 3,” Mr. Fury reported.

Turning 92 this year, Mr. Watson is alive, well and as content as anyone might be living quietly in The Woodlands, a 28,000-acre award-winning, master-planned community with gates opening into streets of homes nestled in the forests north of Houston.

“I’d be in Daingerfield now if I could get the doctors here to move back with me,” he said. In the 1950’s and the first of the 60’s, the Watsons reared three children in Morris County – Kim, Lee and William.

“I’ve got a picture of our Daingerfield scout troop at camp in Oklahoma,” said Lee Watson, now a retired attorney living in Austin. “Richard Harper killed a rattlesnake. He skinned it and cooked it and we ate it.”

Dr. Richard Harper is now a Houston neurologist.

Of the 15 scouts in the picture from Oklahoma, four are now doctors and three are lawyers.

Dr. Richard Harper’s father, Baskin Harper, was the scout master.

“The Harpers didn’t have air conditioning or a television,” Lee Watson remembers. “Their house was the coolest place in town when we were kids.”

It took a summons from the White House to pry Marvin Watson out of East Texas.

Two months after the Mt. Pleasant banquet, LBJ called. It was a Friday, January 29, 1964.

“Are you coming up here?” the President asked.

Marvin and Marion Watson by then had been talking about it for a month, since New Year’s Eve when LBJ sent up a jet to zip the Watsons back to his ranch near Austin to bring in the new year with a handful of friends.

The President and Marvin Watson spoke privately that night and LBJ had tipped his hand.

“He didn’t push me further about moving to Washington that night because he knew what my answer would be,” Mr. Watson said. “I wanted to talk to someone who had worked for him.” Back in Texas, Mr. Watson called on Governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie.

“They were longtime friends of the President,” he said, “and of mine.”

Already, the thing was clear in Mr. Watson’s mind, and just as clearly provisional.

He would leave Daingerfield provided the President gave him title and authority over the whole of the White House staff.

“You know you won’t be able to refuse him again,” Connally said upon hearing Watson’s conditions.

Seasoned in politics and knowing the stakes, the Governor was as blunt as he was clever in framing a compromise.

“We had concluded that I should insist on symbols of authority that no one else might duplicate, such as having the President agree that I could attend any meeting he might have, without exception and without invitation,” Mr. Watson said. He wished to require that the President allow him speaking his opinion in any decision.

“You probably already know this, but make sure that your office is next to his,” the Governor said. “If he agrees to these things, your title makes no difference.”

With the governor’s counsel, Mr. Watson returned to Daingerfield and was ready with terms when the President called.

They came to agreement in moments that Friday night.

“When do you need me?” Mr. Watson asked.

“Monday morning,” the President said. “I want you to fly up here tomorrow.”

In the autobiography Chief of Staff written by Mr. Watson and former LBJ assistant Sherwin Markman, it’s noted that the President had a penchant for taking swift action once he was certain he had what he wanted.

During his 14 years in Daingerfield, Marvin Watson had become a force behind the scenes, a facilitator of unwritten understandings between private enterprise and grass roots government beginning in Morris County and spreading across a region.

When he got here, the politics of water had waited in federal offices for a Texas delegation commitment linked to the Marion County flood of December, 1945. Big Cypress bayou sent as much as five feet of water through the streets of Jefferson that year, triggering Congressional passage of the Flood Control Act of 1946.

Marvin Watson chaired the office that weaved elements of local participation and additional storage for water supply into construction of the dam creating Lake of the Pines, a project in which the feds had no legislated interest beyond flood control.

“You read and study until you understand how the mix of local and state and federal laws and guidelines and policies fit into a workable plan,” said Mr. Watson, who once dreamed of being a college professor. “I loved school. I love studying.”

There was a pivotal moment within months of his February 18, 1951 arrival in East Texas as the new director of the Daingerfield Chamber of Commerce.

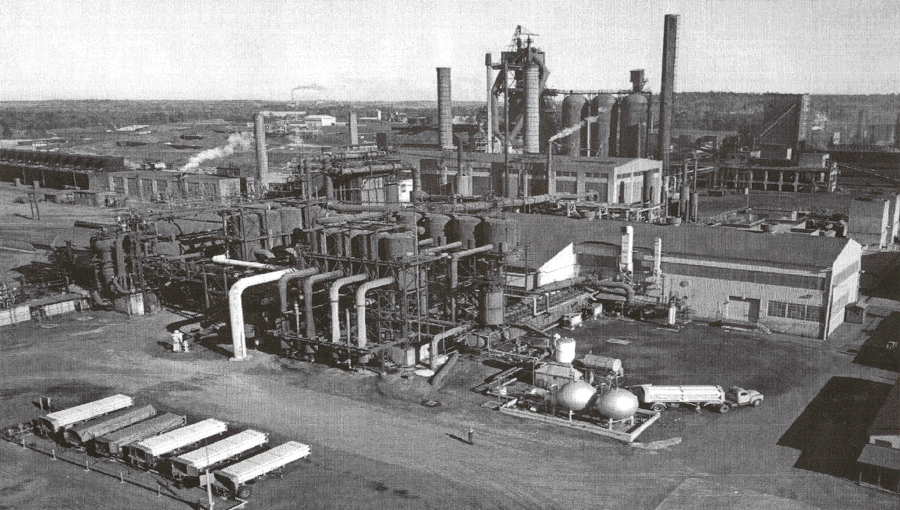

“On Easter weekend that April, I went out to watch as they unloaded earth moving equipment at Lone Star Steel,” he said. “The company had gotten a huge federal loan for expansion – I didn’t understand how much $72 million was, but I’d read that it was the largest loan the feds had ever made.”

As the man behind the desk at the chamber, Marvin Watson began pulling together committees and organizing local think tanks considering demands anticipated with an industrial boom on a scale unprecedented in rural East Texas, a country county seat where leisure time generated frequent church socials and informal gatherings of the patriarchs.

“There really was a courthouse spit and whittle club,” said Lee Watson, who came of age in a place where his father’s influence was a powerful connection. “Before I could drive, I was sworn in after hours by the district judge as the Assistant County Janitor in Charge of Saturday Sweeping & Floor Waxing. The last thing I had to do before I could go eat lunch at the Pearson Drug Store soda fountain was scrub the dried tobacco juice off the courthouse steps every week.”

In positioning the town for the arrival of new families following thousands of new jobs to Morris County, “We did unique things,” Marvin Watson said. “Everybody recognized the sorts of things that would be needed in the way of schools and city services. The financing for those things we understood would be met by the tax base industry brought.”

They called a town meeting and the question on the table was how they might finance new churches.

“If what you want is the best thing for a place, the outcome begins when you put the right question before the right people,” Mr. Watson said. “It may not happen as fast as you want but it will happen if you make clear the need.”

It was decided that if eight families of a denomination would build a church, the town would provide the land, not from government treasuries but from people’s pockets.

“We passed the hat,” Mr. Watson said. “The first was the Catholic church across from the elementary school.

A one-time marine, Mr. Watson graduated Baylor where he’d begun study interrupted by World War II. He worked as a campus volunteer in LBJ’s 1948 senate campaign. Business degree in hand, he landed work as a door to door hearing aid salesman.

“I had a friend who’d graduated and was a great salesman making more money than anybody I knew,” Mr. Watson said, describing the beginning of his tenure with the AcoustiCon Hearing Aid Company.

He was doing reasonably well, but now married with children, the idea of a home in a small town was appealing when he heard about the Daingerfield opening from a friend managing the chamber at Gladewater.

Five years later, he got a better-paying offer from the Gainesville, Texas Chamber.

He was gone two days before Congressman Wright Patman, Lone Star Steel President E.B. Germany and newspaperman Pat Mayes persuaded him to return to Daingerfield with the promise of a new position with the Red River Valley Association.

In the latter days of 1951, he had accepted chairmanship of the Northeast Texas Municipal Water District, the locally-governed body that had worked out details with the U.S. Corps of Engineers in constructing Lake of the Pines for both flood control and water supply.

“With the help of an attorney named John D. McCall, we formed a political subdivision that became the second water district ever built under federal legislation,” he said. “Originally, we represented seven towns. Three dropped out – Pittsburg was almost the fourth when Gazette Publisher Dick White wrote an editorial in opposition.”

The issue was money, a property tax rate north of $3 per hundred to finance construction of a bigger dam to provide water supply until the district was generating water sales.

The Camp County Courthouse was packed the night Mayor David Abernathy invited Mr. Watson to town to rebut the Gazette editorial.

“It went on for hours,” he said. Pittsburg stayed in. Lake of the Pines was built.

The Red River Valley Association had authorization to build lakes but no funding, a challenge with the promise of new work that brought Mr. Watson back home to Daingerfield where he again connected with John McCall.

“I’ve always said that in those years he wrote 80 percent of the water law in Texas,” Mr. Watson said. They forged an alliance with Arkansas that developed resources on the Red River’s watershed.

In 1956 Mr. Watson went to work as an assistant to Lone Star Steel President E.B. Germany, a “brilliant man.

“If you wanted a good story, look into the life of E.B. Germany,” Mr. Watson said. “It wasn’t just Lone Star – his influence shaped the state.”

Vice President Lyndon Johnson became President with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November, 1963.

A Texan in the White House set the stage for an epic battle between the Eastern Establishment and Texas Democrats at the nominating convention in Atlantic City in August of 1964.

“The division was between the conservative and liberal factions of the party,” Mr. Watson said. “The defining issue was the ‘Right to Work’ law.” The liberals backed union authority over the workforce. The conservatives didn’t.

Mr. Watson had worked as a volunteer in LBJ’s political campaigns since his university days.

The company president did not interfere when Johnson called on Mr. Watson. The events that put Johnson in the White House for a four-year term began in March of 1964, when the President sensed mystery in the office of Democratic Party National Chairman John Bailey. With the Presidential Nominating Convention booked for August, Mr. Bailey’s loyalty was to the family of the late President. And Attorney General Robert “Bobby” Kennedy was seeking the party nomination.

LBJ sent Mr. Watson to Atlantic City, where he ultimately spent the summer, his every decision backed without question by the highest-ranking democrat in the land.

The party’s liberal wing had its Eastern State Delegates seated on the floor with the Southern delegations relegated to the balconies. The convention was to open with a film detailing the late President’s legacy followed by an opening night address by Robert Kennedy.

“After five days of chronicling the oncoming disaster, I flew back and reported to President Johnson,” Mr. Watson said. “Believing my job finished, at least temporarily, I returned to Daingerfield.”

That was a Saturday. The phone rang Monday morning.

“Get back on a plane, back to Atlantic City and make it right,” LBJ said. “You’ve got the authority. Use it.”

Mr. Watson was back in Atlantic City Tuesday morning.

Unraveling plans over weeks, he discovered “a carefully orchestrated scheme to displace Johnson and nominate Robert Kennedy. He confronted the party chairman.

“I want an honest answer. I want you to tell me whether or not what’s going on here is a plan by and for Robert Kennedy,” Mr. Watson said.

John Bailey stared, sat silent, then sighed, “Yes.”

“Is his plan to stampede the convention into nominating him for President?”

Mr. Bailey nodded, asked for another chance and promised he’d be loyal to the President.

But John Bailey had already failed the loyalty test.

“On the other hand it had been less than a year since Kennedy’s assassination,” Mr. Watson said. “It remained politically important for continuity to remain between the slain President and a successor who thus far had not won the office in his own right. I was sitting not only with President Kennedy’s choice for Party Chairman, but the man who ran the Democratic Party in Connecticut with a famously iron fist.”

Post Office Lead Clerk Benjamin L. Pippin II displays the lobby’s portrait of Marvin Watson, who served as America’s Postmaster General for a year.

Mr. Watson did not disgrace the party chairman. He fired all but six of the 80 staffers who’d been assembled to run the convention and allowed Mr. Bailey to “retain his public identity of controlling the convention.”

In reality, Bailey reported to Mr. Watson and followed directions.

Robert Kennedy’s appearance at the convention was changed from opening night until the final night. By then LBJ had been nominated. The Texas Democrats had bested the establishment.

Only a handful of insiders had any idea what Marvin Watson had done when the President flew into Mt. Pleasant three weeks after defeating Republican Nominee Barry Goldwater that November.

Mr. Watson was appointed Postmaster General after LBJ left office in 1968.

After a year he left government and immediately landed work with Occidental Petroleum which rose from the 28th to the sixth largest oil company on the globe during his tenure.

He worked in ministry and served as President of Dallas Baptist College before retiring in 1979.