Moonshine provided escape from poverty for Titus County whisky runner on the Back Roads to Dallas

Article reprinted from the East Texas Journal January, 2016 Edition.

Back Roads to Dallas is now at the Mt. Pleasant library.

With permission, I put it where it belongs.

brother’s book “Backroads to Dallas” to the Mt.

Pleasant library.

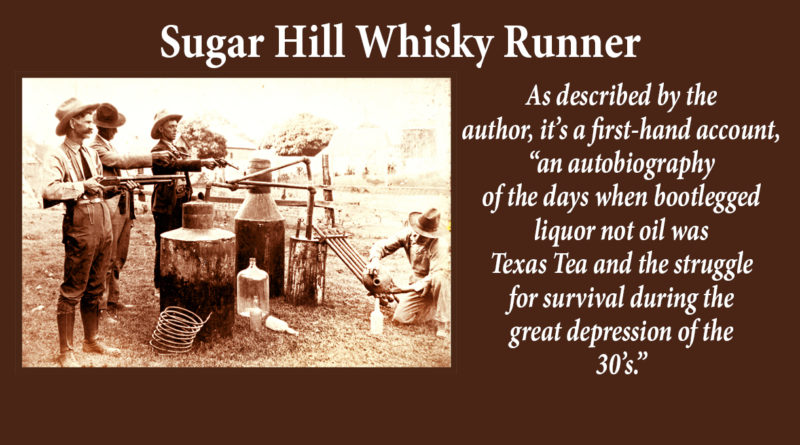

As described by the author, it’s a first-hand account, “an autobiography of the days when bootlegged liquor not oil was Texas Tea and the struggle for survival during the great depression of the 30’s.”

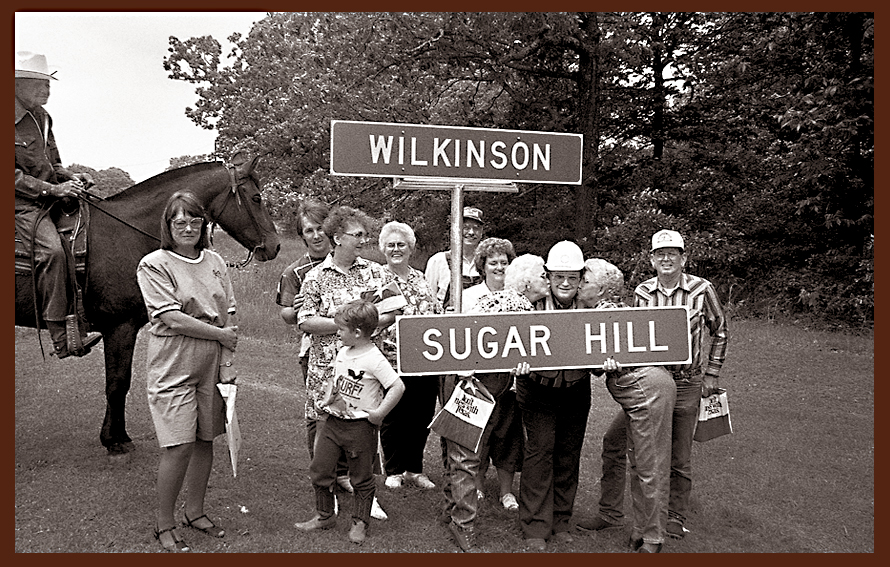

The memoirs of a whiskey runner, a book locking words about the legends of Sugar Hill spun in oral histories, the danger starts in his sophomore year. At 15, he’d come of age knowing the secrets of moonshiners gambling prison time against the quickest possible escape from grinding poverty, subsistence life in the backwoods.

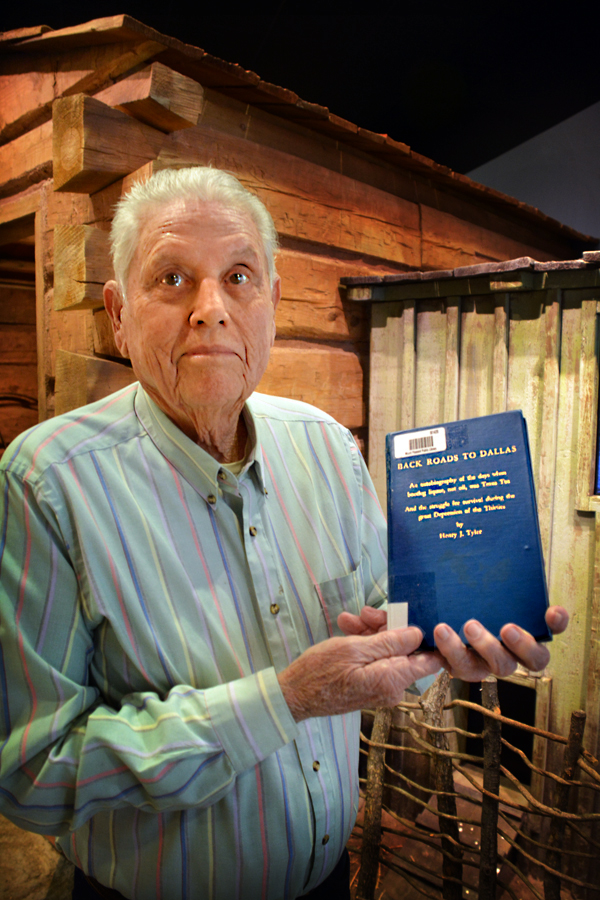

Still guarding his secrets a lifetime later, he wrote under a pen name.

It’s a secret I learned ten years ago when Dean Taylor laid his late brother’s book on my desk. Enough time’s passed.

“Whatever it is, do something with this,” Mr. Taylor said, trusting me with a secret and permission to tell what’s understood by the most moving words between the covers, the writer’s hand written note to his brother on the front flap.

Listen.

“A lot of water has gone under the bridge since we sat down and had a good long chat. Not a day passes that I’m not reminded of something you taught me. As a kid, you were my hero and you still rank number one with me. Your brother, Howard (Hank) Taylor.”

Sitting down to write, Hank signed off as Henry Tyler.

Curiosity provided his first brush with moonshine.

Sent to a neighbor’s home to borrow a lamp wick, it was nearly dark when he arrived. Seeing light flickering from a crack in the smokehouse door, where there should have been no light, he went to investigate and found a neighbor and friend straining amber aged moonshine from a charred oak keg into half gallon jars.

“Come on in,” the man smiled at a moon-struck boy. “Sit down. Ain’t you ever seen a whisky still before?”

“Mom sent me down to borrow a lamp wick,” he said apologetically. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to barge in.”

“I know that, Hank,” the moonshiner said, continuing his work. “And it’s all right provided you understand you never mention it.”

In a time when “the only people who had more than their share of money were moonshiners and bootleggers,” the incident weighed on him.

His days as a rum runner began later that year. A classmate who became his partner in crime said he had a bootlegger uncle in Dallas looking for 20 gallons of whisky and willing to pay a premium for delivery. Hank high tailed it to the neighbor’s smokehouse and had no problems with the math. Whisky he could have for $12 a gallon here brought $15 in Dallas.

That $60 profit on 20 gallons was more money than most of Sugar Hill had ever seen at once.

“I could see myself getting rich and hardly lifting a finger,” he wrote. “This meant turtle neck sweaters, a sailor straw hat and a raccoon coat.”

As much as the money, the excitement reeled him in.

His classmate’s Uncle Ned rolled into Sugar Hill in a new Hudson Super Six, “a touring car that would really move when the road permitted.”

Savoring the taste of risk, the boys climbed in for the ride ready for a first taste of crime in the underbelly of a metropolis and got everything they bargained for.

“Nearly every creek bottom was a mess of chuck holes and Ned had to do a lot of maneuvering to make it through,” he said.

“About nine o’clock that night, just as we were coming out of a creek bottom, a car pulled from the roadside and blocked our path. There were two of them. One man stayed at the wheel while the other got out with a flashlight and a pistol.

“Ned was already getting a pistol from the glove box. When the robber came within about 50 feet and told us to get out, Ned stepped out shooting. Whether it was luck or he was a crack shot I never knew, but his first bullet shattered the flashlight.

“Joe and I had been riding in back and when the first shot was fired I bailed out over the door, taking off down the road. There were eight or ten rounds in the exchange before one of the highjackers called out.

“If you’ll stop shooting, we’ll leave,” the bandit declared.

With the coming of summer, Hank and Joe bought their own car and went into whisky running on a larger scale than the smaller deliveries that kept them afloat during the school year. Their trade that summer crossed paths with “a big time bootlegger and gambler from Shreveport who wanted me to furnish him 40 gallons of whisky a week.”

Knowing the places and understanding the ways of the boys in the trade, bandits in those days could profile whisky runners the same way courts say the cops can’t profile interstate drug mules now.

Hank wrote of chases, being pursued far more often by other outlaws than the occasional lawman they outran with nerve and risky driving the cops they couldn’t get away from with pure speed.

And the cops were plenty canny.

Joe was riding with him when they ran up on a roadblock at the Louisiana line and fell smoothly into the lawmen’s trap.

“I made a skidding U turn and headed back up the highway,” he said, only to discover that moments before they’d cruised past a spot where cops in a second car were watching and waiting in the woods.

“The law beat us to the punch. They pulled across the road, blocking our path. The only route of escape lay across country. Jerking the Model A into low gear we were going fast enough to jump the ditch when I swerved off the road. We tore through a four strand barbed wire fence and headed across a pasture, turned through a thicket mowing down saplings as big around as my arm.”

The shooting didn’t last long, a couple of shotgun volleys beating a tattoo into the hide of the Ford “as buckshot half spent peppered our car.

“Shall I shoot back?” Joe wondered once when it appeared the cops might close within more lethal range.

“Oh, no!” Hank answered and kept barreling along, double clutching and jamming gears at full throttle, hoping any moment to swing up on a road Hank remembered, estimating it to be a mile across country away.

No doubt knowing the country better, authorities gave up the chase.

“Before we found another road we broke through another fence, busted through a corral gate and climbed a couple of steep embankments,” he said, “but we made it, nobody followed and they never tracked us down again on that run.”

He said he once turned down an offer to run between Dallas and New Orleans on a grander scale yet, the promise of regular pay of a thousand dollars a month at a time when common labor ranged from a dollar to three a day.

“Running whisky was exciting but running a little and becoming certified gangster were two different things,” he said. “I just didn’t want to get in that deep.

“Also, I didn’t want to bring shame and disgrace to my family, especially my mother. There never lived a finer woman than my mother.”

A successful and seasoned outlaw when he hit 20, he knew the business and the market from the loneliest depths of remote creek bottoms where the moonshiners worked to the underground webs of distribution reaching out from the city garages and dens of the high rolling players.

He wrote recollections spiced with his opinions.

He said he was 24 the year the law caught up with him working a still.

He copped a plea in exchange for 60 days, time in a cage that made an impression on a man accustomed to running wild, an impression as powerful as the one made the night he’d discovered a source for his vision of riches as a boy curious about light coming from a smokehouse.

He gave up running whisky – several times – in the next two years and it ended when he married.

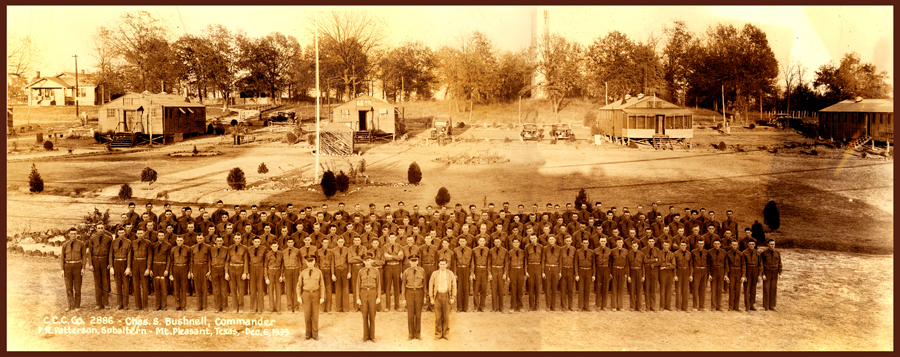

At the height of the Depression, when elected with his promise of a New Deal for America, Roosevelt made good on his word. Backed by a champion, in 1933 Congress pushed through legislation funding boot strap work programs, public works projects that covered the land and lingered for years.

He signed on with the Works Progress Administration for a buck and a quarter a day and two years after that decided if he couldn’t beat working for the government here he’d try his life elsewhere.

Hank and his wife moved to Northern California, “not far behind Steinbeck’s celebrated Joad family from The Grapes of Wrath.”

There he returned to what he’d learned growing up rooted at Sugar Hill. He farmed and raised a family, and when his children were old enough he sat them down to tell them what they needed to understand about the way of the world.

“I explained that I’d made mistakes early in life, and they seemed to understand,” he said.