Local homemakers develop world-class, creekside ceramics

Before Columbus, cutting edge Caddo homemakers here perfected ceramic dinnerware while the average European was still eating off wooden slabs. Five centuries earlier, their grandmas were working out formulas and recipes for preparing clay used by Titus County pottery manufacturers.

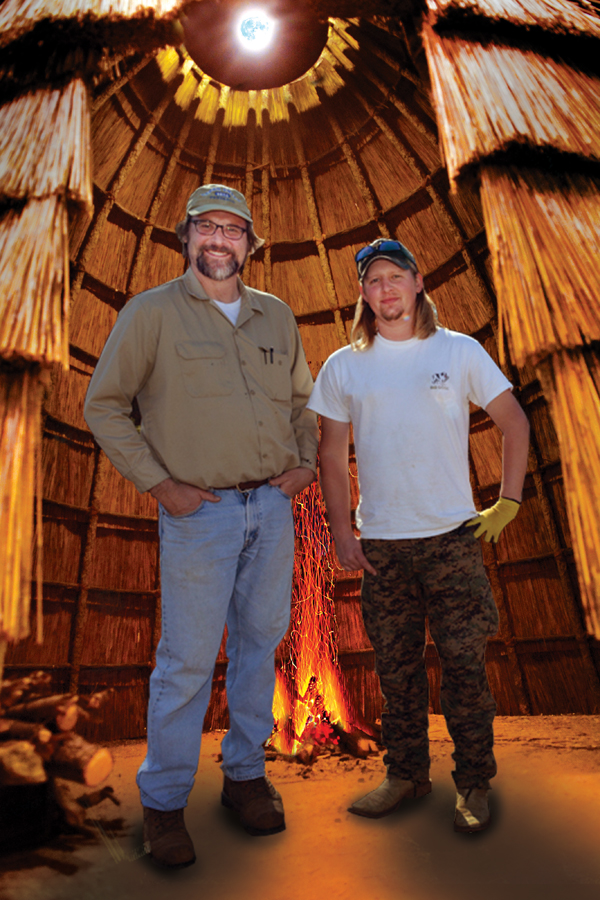

“That means they’d located a good local source for clay with few impurities,” said Eric Schroeder, Principal Researcher directing work done in advance of roadwork beginning the summer of 2017 on U.S. 271. Caddo potters developed techniques for drying clay to powder sifted to remove impurities before making a mud used for shaping vessels fired and later engraved with regionally identifying patterns, Mr. Schroeder explained.

“Caddo ceramics exemplify some of the finest aboriginal pottery manufactured in North America,” says the Caddo write-up from “Texas History On Line.”

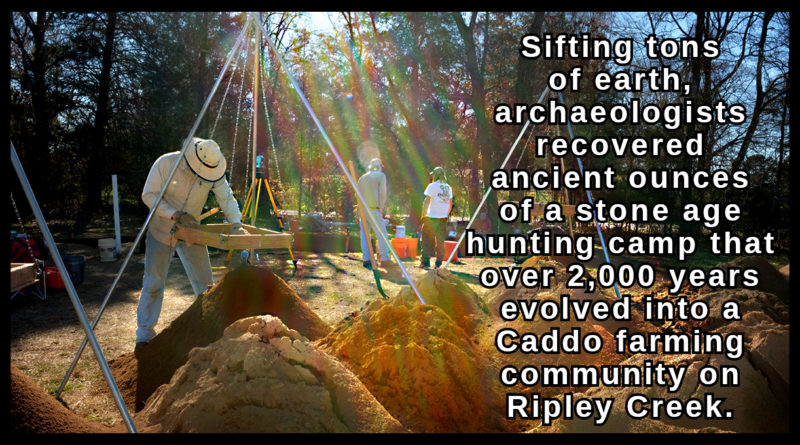

A thousand years ahead of the pottery industry’s appearance here, not a stone’s throw away the archaeological team found record of spear-chunking stone age hunters. Nomads moving in small bands, they made a seasonal camp here and left behind chipped stone while touching up the edges on their “late Woodland Gary and Kent dart points,” said Pittsburg’s Bo Nelson, a local who speaks archaeologic.

“If you’re looking for the people who were native to the Sulphur and Cypress basins, Bo’s the right guide,” said fellow archaeologist Drew Sitters of Austin-based Amaterra. Considering shattered sherds of “Early” Caddo pottery and sifted fragments of stone worked here, the site reaches back 3,000 years, into “Archaic” times, Mr. Nelson said.

Here, evidence of “Late Woodland” era (1000-500 BC) seasonal camps blends into “crude” pottery, evidence of year-round housing and establishment of a farming community at the site on Ripley Creek.

“Woodland” is archaeology lingo for an extended period of generations continuously developing a culture in transition that here evolved into the Caddo, a people whose lifestyle made them predictable for field veterans.

Pittsburg’s Mr. Nelson learned to hunt evidence of Indians while trailing behind a great grandfather plowing his fields along Little Cypress Creek in northern Upshur County.

Later, after earning two degrees at Stephen F. Austin, as lead author of a paper written with Texas Historic Commission’s Tim Perttula, Mr. Nelson described an “Archaic” point near another early Caddo homestead on Little Cypress.

As identified by the Big Brains, the North American “archaic” period stretches from the time of Christ back to the Ice Age.

Basing conclusions on a mix of fossil remains from the Red River and stone tools, the smartest guy in the room said the earliest people in the Caddo territory including Northwest Louisiana, Southwest Arkansas, East Texas and Southeast Oklahoma came following “Giant Ice Age Bison, camels, the giant ground sloth, the elephant-like mastodon,” and other now extinct ice age animals, Frank Schambach said in a paper presented at the Caddo Adais Convocation in 1992.

He said the earliest known East Texas visitors looked and dressed like Eskimos.

“We know this because many of the stone tools they left behind are for preparing hides and for making the bone needles necessary to sew them into clothing.”

Two feet deep into a one-time community dumpsite near Ripley Creek, Mr. Nelson paused in his digging and made a sweeping gesture over the creek bottom.

“The Caddo built atop fingers of land rising above the annual floodplain,” he said. Frontiersmen, Caddo like the early settlers along Ripley Creek were different. They didn’t bother with fortifications.

“There are theories as to why, but what we know is that they lived peacefully for a thousand years,” Mr. Nelson said. “By contrast, most of the Eastern Tribes were so war-like that they built palisades around defended villages.”

By 1000 AD, the Caddo were better armed than most people in North America, Mr. Schambach said.

While the archaeological record revealed in weapon points shows old timers hanging onto spears, the up and coming generation of progressive farmers and hunters along Ripley were improving the bow and arrow.

“Judging from the performance of modern replicas, they had draw weights that could drive an arrow at 170-feet per second,” Mr. Schambach said. They also had a regional monopoly on bois d’arc, a premier wood for the manufacture of bows. Their skill as potters evolved into their production of salt, a premiere trade good.

“They made large shallow bowls for capturing and evaporating water flowing from salt springs along the Red River,” Mr. Nelson said.

The local height of Caddo communities was a relatively narrow span from about 1200 to the mid 1500’s when smallpox arrived with the first Spanish expedition passing through Caddo Country.

By then the Caddo had storehouses for grain and they were traders, dependent on good roads. Early surveys from the time of the first permanent European stock settlers show two Indian roads intersecting a mile from Ripley Creek in present-day western Franklin County.

Scholars researching the trail of a scouting party from the remnant of Hernando de Soto’s Spanish Expedition that passed through the region in 1542 a Spanish Expedition, theorize the described route coming from northeast into Texas near present day Texarkana also describes Caddo villages found on Cypress Creek as the Spaniards followed an existing Indian route south as far as the Angelina River.

Roads provided for trading a flow of goods built around salt, ceramics, bois d’arc bows.

“Part of the secret of the Caddo people’s ability to lead peaceful lives was probably their great ability as traders and manufacturers,” Mr. Schambach said.

Mr. Nelson believes the Caddo lived in peace because of the density of their population, the sheer numbers of their communities after they began farming.

Hundreds of years before the best known Indian tale from Ripley Creek, their farms along the streams of the Cypress and Sulphur watersheds appear to have vanished.

“Smallpox,” said Mr. Nelson. “In the Middle Caddo era typically found here, there are small family cemeteries. “During the late Caddo phase, after the first Europeans came through, you find evidence of epidemics and cemeteries with hundreds of burials.”

With New World Conquistadors returning to Europe with Aztec gold, in 1539, Hernando de Soto set sail for the Americas in search of riches.

Didn’t work. Two years after he landed in Florida, the remnant of his 600 men buried him on the shore of the Mississippi where he died with a fever. The expedition passed through East Texas when a reconnaissance party led by Luis Moscoso began looking for an overland route to New Spain (Mexico.)

While not warlike, the Caddo proved not to be pacifists. Spaniards looting Caddo farmstead grain storages were met by collected bands of warriors after their search for a road into Mexico failed.

“The Spaniards declared them the fiercest fighters they had engaged anywhere in the Southeast, which included some very fierce fighters indeed,” Mr. Schambach said. “In two battles, the Spanish were nearly defeated despite their steel weapons and their horses.”