Rebel lived life on his terms

At the funeral, they said Dr. Clint Davis said there were lots of stories about Glenn Justiss, including some that wouldn’t be told as a part of the service. Here’s one from 20 years ago.

PROLOGUE

“You really voted for him?” Glenn Justiss asked, his voice at once amused and incredulous.

Again I confirmed what he obviously interpreted as a lapse of good judgment.

Smiling, shaking his head, Glenn slapped a big paw down on my shoulder, a manly gesture of genuine compassion.

“I think you’re an honorable man,” he said, “and I see a good out for you, even in this dark circumstance.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“You need to go home and slit your own throat.”

If nothing else, I was interviewing a man of conviction.

By HUDSON OLD

Journal Publisher

COCK FIGHTS, CREEPING SOCIALISM AND ENGLISH NOBLES

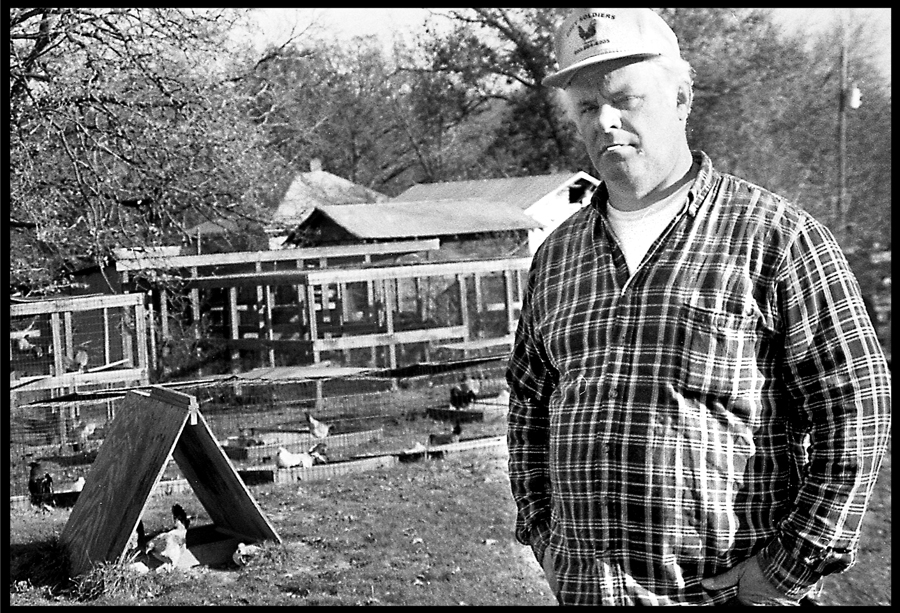

If Glenn Justiss is right, this thing is bigger than us all. A proponent of numerous conspiracy theories, he measures thoughts from odd angles.

He strolled through a lawn of A-frame huts, home to 300 fighting cocks, each with a foot tethered on an eight foot cord.

“If I unleashed every one of these birds, they’d fight ‘til there was just one left,” he said. “It’s in their blood, but if I let that happen in Texas, I’m a criminal.”

He said he’s galled by the “hypocrisy” of “socialist humaniacs.

“Need me to spell that?” he asked. “It’s the same crowd that wants to ban rodeos, hunting and fishing. People who believe they have the right to legislate morality aren’t liberals. They’re socialists.”

But wait, there’s more.

“‘When government increases,” he said, “freedom decreases,” then added the attribution — “Thomas Jefferson.”

He said Mr. Jefferson, architect, designer and principal author of the constitution, was a cock fighter. He put George Washington, Andrew Jackson and Senator Kleberg, “of King Ranch fame,” on the list. While continuing to take issue with numerous policies of Abe Lincoln’s administration, he praised Lincoln’s response to those who opposed cock fighting.

English nobles once barred commoners from cock fights at Number 10 Downing Street, current residence of the British Prime Minister.

“King James,” he said, “the man who translated the Protestant Bible because he believed in the right of the common man to have the truth at hand — guess what?”

“Cock fighter?” I guessed, cleverly.

“See, ten minutes with me and you’re already getting smarter,” Glenn grinned, rolled his toothpick between his teeth.

ECONOMICS AND BREEDING

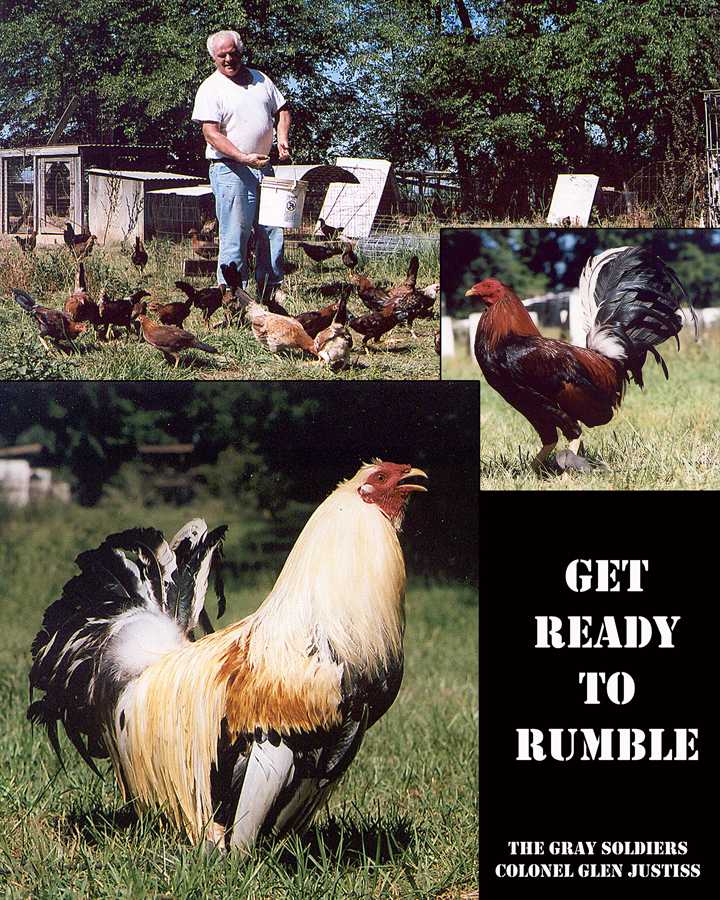

He rules a house and nine acres, points out that the export of his Gray Soldier fighting birds pumped better than $10,000 into Clarence Sullivan’s Daingerfield feed store’s receipts in the current year.

“The development of the Gray Soldier line is my contribution to the local poultry industry and the area economic engine,” said Glenn, whose thoughts on breeding extend to a self-professed aversion to authority.

“A common-bred man,” he says, “can’t handle authority. Stick a badge on anybody and you can test the theory.”

The great grandson of a gent described in The Historical Encyclopedia of Texas as a “soldier of fortune,” Glenn wiggled into the world 50-odd years ago. His family came from a farm near Boggy Creek, one of the remaining remote areas of the Geezerplex along the northern stretch of the Titus – Morris County line.

“Kinda backwoods clannish people,” Glenn said of his ancestors. “If they saw you coming up to the

In 1948, about the time Glenn was cutting teeth, the Justiss family operation was featured by a Bowie County publication as the prototype of modern East Texas farms.

“Three story metal and concrete barns are so erected that you may drive into them on three levels,” the story read, and went on about their annual 15,000 bushel sweet potato harvest.

By birth and the experience of his youth, Glenn can stand in his dusty old once-upon-a mule barn and weave barefoot farm-boy tales, but with an atypical spin.

PHILOSOPHY OF WORK ETHICS RELATING TO NATIVE POPULATION

One day, Glenn said, he decided he needed some money of his own. Catching his pony he swung aboard bareback and barefoot to boot, riding north to seek his fortune picking cotton on the next place over.

“When you rode this road in those days, you just passed from farm to farm,” he said.

It was the time of the cotton harvest, the one time of year when there was cash work for every member of every farm family. Men, women and children, black and white, pushed themselves from daylight to dark harvesting. They covered the fields with no end in sight to the work as Glenn rode to the scales set up in H.V. Evans’s field. Tying his horse in the shade Glenn took up his sack and went to work.

“I quit after I’d made eight cents,” he said, putting a wrap on his cotton picking days.

Twenty years ago, he bought a nine-acre corner, including the barn, a derelict and worthless tenant shack, and the old four-room house from Mr. McCollum’s widow, Miss Hattie.

“Look here,” Glenn said, hand moving from the stall door to an ancient tree fork nailed for a hook to the barn wall. “This is the work of a prosperous man. To prosper he had to be so tight he must of squeaked when he walked. He didn’t go to town and buy a hook to hang his mule halters.

“The corn crib’s over there,” he said, pointing across the barn hallway. “All night his mule stood in this stall eating corn and come daylight man and mule got out and did more manual labor in a day than we’ll do in a month.

“Being prosperous, I’d suspect they had meat two or three times a week and they valued a hog by how much lard they boiled down when they killed him.

“They lived for church and work. Fighting cocks and race horses didn’t fit their schedule.

“My Uncle Adron up the road is pushing 90 and if we went up there right now and said, ‘come on, let’s ride over to the Wildflower and eat lunch,’ it’d be pure foolishness to him. He’s got so much to do it takes daylight to dark and there’s no let up in him.

“I’ve developed a more balanced work philosophy,” Glenn said, “that lets me focus at will on perpetuating the most noble blood line in the poultry industry today while maintaining a completely flexible nap or meal-time schedule.”

‘RESISTING TYRANNY’

Given his earlier referenced issues with authority, Glenn wound up his school days sorta like his cotton-picking career, by mutual agreement with school officials in Morris County.

“I’ve always,” he said, “resisted tyranny in any form.”

Among his careers and enterprises, Glenn was himself once a lawman, Chief of Police of the now defunct incorporated community of Monticello. Another old Titus County farm community, an influx of construction personnel arrived in Monticello to build a power plant in the 70’s. An incorporation election was held and the town voted itself wet.

Glenn came to maintain law and order around the new beer store and the old community grocery store converted to a pool-hall, dance-hall honky tonk.

“I had a perfect record,” he said, rolling his toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other. “I never made an arrest.”

FIGHTING COCKS

Prior to the sanitation of human conflict with nuclear weapons, napalm, wars in the sky and biological attacks, in the barbaric age of lance and shield, “before technology advanced to allow safer methods of mass extermination from a distance, when killing required standing eyeball to eyeball,” Alexander the Great advised his men to observe the courage of fighting cocks, “to be as brave as the feathered warrior,” Glenn said.

“A rooster doesn’t care how much money’s in the purse or who’s watching,” he said. “Confronted with another rooster, he immediately fights. For 3,000 years that we know men have marveled at the fearlessness of game cocks.”

Strolling along the trace of an old county road that once cut between Mr. McCollum’s mule barn and his house, Glenn used a fisherman’s net to scoop up a free-range hen who’d been scratching at fall leaves. In a lot beyond, roosters crowed at the sun.

He pressed the squawking hen in his net to stillness, fingers smoothing back her wings before he drew her out, smoothly conducting a physical exam, reading her like a book. Marks on one toe and her beak showed her bloodline.

“To breed for the right things, you’ve got to know more than bloodlines,” he said. “You look for a long breast bone — the keel — wide tail feathers, heavy plumage and a broad, flat back.”

He thumbed the hen’s slick leg. “You want at least 30 scales down the leg and you look for disposition — you can’t train a bird that wants to fight when you hold him. We use a 10 power jeweler’s glass to look in the eyes, searching for wide shadows, color and rings around the pupil. We don’t know if that’s something in the breeding or just a sign of good health, but you learn to breed for almost intangible things. There are lots of pretty birds, and lots of good birds, and just a few that have the extra bit of something that makes them champions.

“There’s more to this than breeding for meat and eggs.”

Drawing back the hen’s feathers, he smoothed the flesh over a tattooed date of birth.

“Ninety two,” he said, dropping her open winged to glide back to her leaves. “Great brood bird, been living the good life eight years,” he said. “That would be as opposed to the five-week lifespan of poultry produced to be slaughtered en masse for chicken nuggets, micro-wave meals and pool side barbecues, but nobody who appreciates the efficiency of modern agriculture wants to deny producers the right to put chickens frozen in grocery stores.”

TRAINING SCHEDULE

He handles a cock as many as two and three times each day, exercising him, moving him from grass to a training pen cushioned deep with wood chips, to a hands-on table, to dirt, back to his pen. The moment the mood strikes, and not a moment before, Glenn takes a break.

Frequently, that means a trip to the Wildflower Inn at Hughes Springs where the daily buffet includes several kilos of chicken fried steaks, vats of different styles of gravy. His waitress automatically brings him a platter of fresh sliced tomatoes.

“This,” he said, settling in with a heaping, mostly gravy covered plate of meats and fresh vegetables, “is at least a three times a week deal.”

A guy with eyes as piercing as a Saturday afternoon movie pirate dragged up a chair. A dapper English driving cap took a needed bit off the edge of his look.

“Meet Mike Glover, three-time Cocker of the Year at Sunset, Louisiana, the toughest pit in the world,” said Glenn.

Each year, Mike comes to East Texas from Winchester, Kentucky, training birds for East Texans for competition in other states.

Birds he’s trained and fought in the Phillippines have earned standing ovations in a country where cock fighting is the national sport.

“You’re looking at a legend,” Glenn said as Mike bellied up to the Wildflower Inn table, digging into a plate of chicken fried steaks.

THE STUDY OF CONFLICT

A student of conflicts, while Glenn early identified fallacies associated with farm labor and traditional education, his mind bloomed like a perfect spring around fighting cocks.

“I was hooked,” Glenn said, “the first time Newell Landrum took me to the cock fights at Broken Bow’s Noey Lake Park at C & D Club.”

He learned of local legends.

Mr. Landrum told a story about Jim Barnett’s Barnett Wonder line putting Titus County on the cock fighters’ trading map earlier in the century.

“Newell’s story was that a band of gypsies came through with an unbeatable fighting cock,” Glenn said. “Before they left, Jim traded them out of their bird and used him to breed a line of birds that were all but unbeatable.

“Years later, a fellow asked Jim what kind of birds they were. Jim said, ‘I’ve always wondered,’ and thus was born the name Barnett Wonder,” he said.

Now, birds Glenn breeds here have been shipped coast to coast and beyond, demand groomed like his blood line with a marketing effort based on performance. Three times in the 90s, the Gray Soldiers have won the January derby at Sunset, a one blinking light country crossroad Louisiana town outside Lafayette, “the toughest pit in the world,” Glenn said.

BIDNESS

Nearly all of the 300 game cocks Glenn raised on the old McCollum place this year track their linage back to a pair of birds he bought from an Arkansas breeder in 1971.

While Oklahoma, Louisiana and New Mexico are the only states that allow fighting, game cocks can be bred anywhere. Glenn’s East Texas farm is well situated.

“I sell a lot of birds in Oklahoma and Louisiana,” he said, but his market reaches further. Each month’s 180-plus page issue of Game Cock magazine features 24 full color glossy pages and one of those color slicks advertises Glenn’s Gray Soldiers.

“If you want to compete at the highest level of competition in the world, we are the source,” one ad bluntly states.

He cashes in when his birds win, building a reputation based on a growing record. Friends and neighbors Tommy Golden and son Paul won Cocker of the year at the AklaTex Pit in Ida, Louisiana with game cocks descended of brood fowl from the Gray Soldiers.

Ladd and Todd Freeman have twice won the Texoma Hawaiian Derby, “the biggest, toughest one day derby on the planet,” with birds originating with Glenn’s bloodlines. In the 90s, he introduced “the Albany blood” to his line, birds developed by a New York democratic party chairman.

The Gray Soldiers have been shipped coast to coast, from Lima, Peru to the Phillippines. Agents for a buyer in Mexico City bought a third of his current crop.

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re for or against the sport,” he said. “The question is, do you have the right to do it? There’s clearly no constitutional prohibition, just the objection of activists who want to see competition banned.

“I’m not a criminal,” he said. “I’m an outlaw. It takes a discerning man to recognize the difference.”