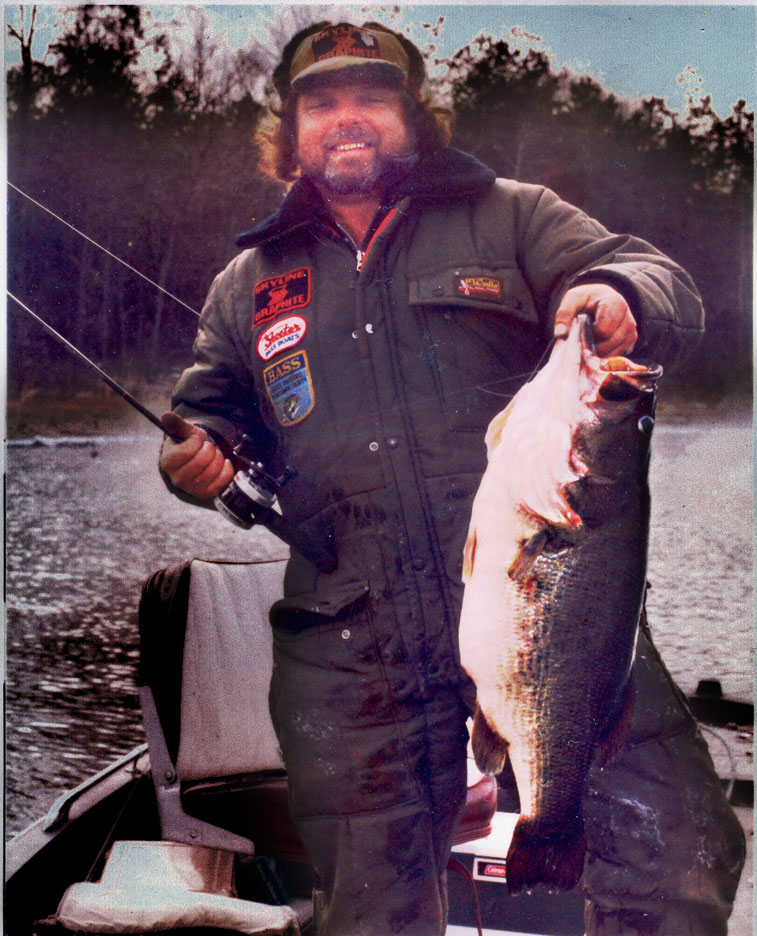

Welsh Delivers Record Bass at a Bad Moment to Remember what he Forgot

Not long after the Welsh Lake dam flooded Swaunano bottom, Bill Ocker reeled in the biggest bass ever landed in Texas. December 23, 1983, he knocked off early enough to get home to the lake at winter twilight.

“The water in my live well was a frozen block,” he said. The soft bite he got the moment a short cast hit the water turned into a rod-bending dive when he set his hook, a fish “pulling like a horse.

“It was a bad time to remember that I was fishing with an old Garcia reel I’ve always liked,” he said. “It’s got a leather washer that controls the drag and it doesn’t work unless it’s wet.” A drag is designed to hold tension while letting a fish run until it’s too tired to fight. Bone dry, the vintage Garcia’s leather drag held his line fast and in danger of snapping from the moment he set the hook.

Rod high as he could reach turned the fish toward the boat, into the mouth of a net at the long end of his other arm running on experienced auto-pilot, swinging aboard a fish that changed everything. Easy enough, with a touch of fisherman’s luck.

Built to burn coal in the 70’s when America was running out of gas, the Southwestern Electric Power Company’s (SWEPCO) Welsh Plant marked the beginning of a new age in the creek bottom draining into Cypress near Cason.

Conversely, the salty sorts national energy policy caused to be drawn here by the fish are more like the old spirits at rest in a cemetery on a little bluff along the lake shore, people seasoned to make do, graves marked with iron-ore rocks their survivors dug from the ground where they’re buried. (See Story, page 4)

The cold of the year is the height of the sportsman’s season.

Aboard boats coming off trailers at the ramp before dawn, they vanish into a rise of warm water mist hanging low on the lake. The sound of traffic a half mile away on Farm to Market 135 fades away. A lake with one way in and one way out, no piers and no boat houses, the only other fishermen here are wading birds working ribbons of beach.

Beards of fishermen caked with ice at the winter height of the fishing season testify; this isn’t a place for the feint of heart. The same elements testing the will of sportsmen once measured the ancients who named the Welsh Valley’s stream “Swaunano,” translated “Good Water,” said historian Traylor Russell.

At left, Bill Ocker’s 15-pound 3-ounce Texas Record bass put Lake Welsh on the sportsman’s map and made Mr. Ocker a fishing guide and a regular on the televised Honey Hole fishing show. The lake’s a destination for tournament fishermen.

Going back to the 1930’s and highway department studies, there wasn’t an archaeologist in Texas who could stick a shovel in the earth where Swaunano crosses under today’s U.S. 49 without finding sign.

When Europe was eating off wooden slabs, Caddo housewives were setting up pottery factories here, firing ceramics. A thousand years later, Caddo braves were arms merchants trading the Plains Indians bois d arc bows for Spanish horses.

Four miles up the road toward Mt. Pleasant, there’s the Hinton Collection of Caddo artifacts dated and classified by the guy tracking Northeast Texas settlements back to stone-tool times when nomads passed through with the seasons. Pittsburg’s Bo Nelson is the state historical commission pick of those researching to understand prehistoric culture in East Texas.

In historical times, but before the arm of the law was long enough to reach Texas, a white man turned Cherokee beat a man to death with a chair on the porch of an Alabama general store. The deceased never called Kendall Lewis a “dirty Indian” again. A marked man in Alabama, Mr. Lewis came to Texas. He’d lived years on Caddo Lake before being made Texas Republic President Sam Houston’s “ambassador to the Indian nations,” Mr. Russell wrote. He built his home on Swaunano, but quit Texas for Oklahoma, moving with his Indian wife when most of the last of the Indians were driven north into Oklahoma.

Fishermen are the latest in the salty sorts here.

“Most of them have traveled more than 50 miles to get here,” said Welsh Plant Environmental Coordinator Michael Brice. Sporting an undergraduate degree in wildlife management and a masters in fishery science, SWEPCO hired him away from Texas Parks and Wildlife.

Lake Welsh has been a TP&W study since before Mr. Brice’s years with the agency. Black Bass are native to its waters. In 1975 and 1976 the department successfully stocked larger Florida Bass, establishing new genetics. What’s working here is unique enough that the state gets federal money to monitor and manage the lake for the fed’s Inland Fisheries Division.

Back in his native Missouri, in the mid 1950’s Bill Ocker began a 13-year run at Lambert-Saint Louis Airport where McDonnell Aircraft Corporation thrived on military contracts. In Japan he ran crews repairing F-4 Phantom II jets wounded in Vietnam. McDonnell was McDonnell Douglas by the time a lull in the war-time military economy changed his plans.

“We’d cut back enough that they wanted me to work nights,” he said.

So he quit. He’s sold cars. He went to Florida thinking of buying a boat and guiding off shore fishing trips. Hurricanes changed his mind. In Texas he made more money selling cars before turning himself into a writer.

“I wrote a story for a fishing magazine about a big drum I caught bringing in the New Year on Lake Granbury south of Dallas,” he said, which happened about the same time Fisherman’s Eye Magazine moved its office address to a Mt. Pleasant post office box. Bill Ocker signed on as a writer, ad salesman and boat show booth front man pitching a fisherman’s magazine.

The magazine’s heart was on the road. The job came with two fine boats and a tricked out custom van mobile office. The magazine published reports from lakes in the corners of four states with East Texas at its hub and Mt. Pleasant at its heart.

In the same era the pending depletion of gas reserves triggered construction of Welsh, the biggest generating giant in Texas built the lignite-fired Monticello Steam Electric Station with a second hot-water reservoir on the other side of Titus County. Lake Bob Sandlin was built backing up to the new dam creating Lake Cypress Springs and the newer dam creating Lake Monticello.

Filtered through the lens of Fisherman’s Eye Magazine, Mt. Pleasant was the centerpiece of Bill Ocker’s dream. He had a home on Lake Welsh when that bubble burst and the magazine went belly up. He took work as the maintenance director at the county hospital.

There was a combination bait shop, country store and RV park on Lake Welsh the night he rushed his monster bass home to the bathtub before getting the store owner to open up so he could put his fish in the store’s minnow tank.

By Christmas Eve morning TP&W officers were there with scales. By afternoon there was a rising faction wanting the 15-pound-3-ounce weight disqualified, suggesting the fish got fatter eating minnows before being being moved to a minnow vat of its own.

An overnight star, Bill Ocker made put Lake Welsh in the Metroplex news. Sometime between Christmas and New Years, he negotiated an exit from his hospital maintenance career to be a professional fishing guide.

In February, his record put him on the cover of Honey Hole Magazine, an outfit operated in tandem with a televised weekly fishing show. Lake Welsh and Bill Ocker became regulars.

“Here’s how it was,” he said. “When they got in a pinch for somebody, they’d call me up.” He put the show on Welsh, Lake Bob Sandlin and Monticello. He met them to find fish on Lake Fork, near Quitman.

In 2011, the Welsh environmental group worked with TP&W in creating new fish habitat. There’s a TP&W website map showing where they made 15-pound concrete anchors to sink shoals of cast-away Christmas trees providing two types of cover.

That worked, say TP&W winter “creel survey” results.

“There’s cover for fish waiting in ambush and cover for hiding the fish they’re hunting,” said Mr. Brice, the plant environmental officer. “Largemouth bass were more abundant in 2015 than in the last study done in 2008, before we upgraded habitat. The average age of a sampling of 14-inch bass was a year and and a half, reflecting a rapid rate of growth.

“The most significant factor in rapid growth is a warm water lake with a longer growing season for everything supporting aquatic life,” Mr. Brice said. “It’s what’s made the Florida genetics prove up the perfect fish for the perfect environment.”

The lake’s current management plan calls for increasing oversight of a delicate balance between open water and a rise in aquatic vegetation from invasive species. They’re on top of it.

Some 40 years into the show, advances in oilfield technology have unleashed new reserves of natural gas, again reshaping the generating industry. Rafts of new environmental regulations governing coal and Texas-lignite generation closed the Monticello plant, ending the hot water era at Titus County’s Lake Monticello.

“What happens next, there’s going to be a rise in tournament fishing on Welsh,” said Mr. Ockenhauser, whose full name appears in the state registry of records.