Hearts of steel beat with the fire in Henderson Manufacturing

PITTSBURG – Fire, high pressure, high voltage, guys layered over in protective clothing and working molten steel from behind shields. That’s the brute picture of a foundry operation east of Pittsburg on Farm to Market 557 that began because Bill Henderson was intolerant of the service his Mom and Pop operation received from suppliers. Running on a shoestring and selling his invention out of the back of his car, enough was enough.

One of 15 children, Yvis Davis “Bill” Henderson was a mental mix of imagination and nuts and bolts sweat intellect. He was in his teens when he began working as an apprentice at Pittsburg Foundry. From there he went to a machine shop.

“He had an eighth grade education, a mechanical aptitude and a common sense understanding of business,” said Larry Bailey, whose 50-year tenure at Henderson Manufacturing spans four generations of a family business.

In an era when American foundries are closing the doors, Henderson Manufacturing is humming.

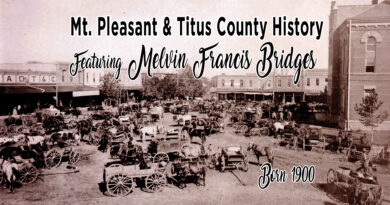

From the top, meet Karen Wright, Larry Bailey and Mitchell Wright. Mother and son, Karen and Mitchell are the third and fourth generations of Henderson Manufacturing. General Manager Larry Bailey’s 50 years here reach back to the era of company founder Bill Henderson. A dropout whose life with steel began where Reverent Burrell Cannon built his Ezekiel Airship before the Wright brothers flew, when the foundry closed 70 years later they gave Mr. Henderson the company sign sitting on Karen’s desk.

Coming from the top, that’s Gonzalo Arellanos checking work above Salvadore Dominguez, posing with sand molds used in casting. In the third frame are Torrance Hollomon (left) and John Peres.If you work here, you’re tested with fire, trained to safely handle high heat, high pressure, high voltage and burning molten steel.

The front office brain is Karen Wright, third generation, a book keeper who came home 12 years ago after uncles who’d moved on to new opportunities sold out to her mother.

In the company story, Larry Bailey’s the rock, she said.

“He called and said he needed help,” she said. Willful, hard-business minded as the steel products her father’s plant produced, Carolyn Henderson Jackson was a widow battling four kinds of cancer opening an edge to creeping dementia when her daughter came home.

Staying out of debt and channeling profits into land and cattle, she was running the company just like her father had when Karen arrived. Foreign producers, mainly China and Mexico, were eating away the oilfield market that had become the company’s bread and butter.

The right mix of Mr. Bailey’s understanding the market and commitment to the same quality Bill Henderson demanded coupled with Karen’s accounting savvy recast the operation.

“We’re a diamond in the rough,” she says, a dozen years later. “We’re the high end steel boutique. Contracts that are a drop in the bucket for the big places are watersheds for us. You take care of your customers and word gets around. Business we lost to economies of scale and overseas production is coming back to us because they value our quality. It’s satisfying to watch.”

Hard drinking, hard living and driven, her grandfather could “take a bucket of bolts and parts and turn it into something that works,” she said.

“The best and the biggest story on the street about him is about the day my grandmother gave him his choice – he could have his drinking or he could have her, but he couldn’t have both,” Karen said. Bottom line on that account, “Margaret Ethyl Bynum was the apple of his eye. From that moment, he never took another drink.”

And he had a heart for drunks. The grapevine stories about him recruiting workers at AA meetings are true, Mr. Bailey said.

“He’d give a man a chance,” Mr. Bailey said. “From the first day they hit the door they had to meet his standards. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. Since he’d built the place he knew it so well he could come in off the road and walk through and spot anything that didn’t meet his expectations.”

Husband and wife, he and Margaret were a team. She handled the office with the same expectation that made him intolerant of anything short of the attention to fine edges they demanded.

College classes in drafting made Mr. Bailey a high-end hand at 19, sent to the wood shop where the company produced wooden facsimiles used to cast sand molds to customer specs, work that in the early years supplemented production of the Hydra-Juster.

Straight from the founding father’s head, a tool that cut the time for adjusting the tracks on bulldozers and any other machinery moving on tracks from hours to minutes launched the company.

“Mr. Henderson could walk through a scrap yard and see what he needed to make something he wanted,” Mr. Bailey said. “He could study the way a piece of equipment worked and design his own.”

In the early days, his claims about his Hydra-Juster were too fantastic for equipment manufacturers to believe. Then he caught the attention of Alis Chalmer, one of the majors.

“That was it,” Mr. Bailey said. “They had more resources and more engineers. Overnight, instead of cobbling together and welding up his own design to match every make and model that he recognized as market potential, he had the design teams to create molds they could pour.”

A small-time player by American industry standards, it was Bill Henderson’s demanding nature that caused the break with contracting foundries. Mr. Bailey heard the story first hand.

No matter how talented his mind for product design, nobody could reasonably have expected Bill Henderson to do what he did. Design and manufacturing that begins with molten steel involves math compensating for heat-related expansion and contraction creating brain-bending calculus, some in-depth physics.

“His ultimatum was if they couldn’t satisfy him he’d build his own foundry,” Mr. Bailey said. Reading that as presumptuous, he was scorned. Ignoring critics the same way he’d blown by equipment manufacturers who believed his claims too fantastic, he gathered equipment from across the country. He built cranes and hoists from scrap yard parts, auto rear ends, frames and transmissions.

Today, Henderson Manufacturing accounts range from the needs of single-product entrepreneurs driving to cut exclusive deals prohibiting the company from supplying competitors to insatiable drive for production for oilfield equipment, a boom or bust market dependent on the energy market.

It’s a balance, a tight rope ever honing Henderson Manufacturing’s high-wire act.