Wandering cast of musical show settled and blended into the misty legends of Sugar Hill

SUAGAR HILL – When the world was quieter, Al Riddle remembers the sound of his grandmother’s guitar.

“Saturday afternoon she’d come out on the front porch and start playing and from as far away as I could see her I could hear every note when she was picking her guitar,” he said. “She wasn’t a small woman. She milked cows and she had strong hands. She was bad about breaking strings.”

A singer and a dancer, Gussie Elder-Blalock was a professional entertainer with the Elder Family Show when she arrived here in 1918. There was a “professor” of music who traveled with the show, Mr. Riddle said and the “family” was a blended mix of relatives, orphans and runaways. The professor taught all of them music and as Gussie told the story, everyone learned to play two instruments.

“Until I was 13 I lived most of the time with my grandparents,” Mr. Riddle said. “On Saturday afternoons the community gathered at our place. There was food and there was music. They moved the furniture out of the house to make room to dance. It was a wonderful place. I cried like a baby when my folks moved our family to Dallas.”

Gussie may have been the child of a brother of the show’s organizer, Pleas Elder. Children of Pleas and Lydia Elder who traveled with the show were sons Bill and Willie and daughters Bennie, Atta and Josephine. Gussie was a niece of the sisters.

The first of the Holt family to make Sugar Hill home came with the show.

“George Holt was my grandfather,” Evette Holt-Birchfield said. “His family came from England and he was born in 1898 in Illinois. After his father died his mother re-married.”

The family story is that George Holt’s family moved to Canada.

“He didn’t get along with his step father and when he was 14 he ran away,” Evette said.

His son, Robert Holt, remembers George’s story of leaving Canada on horseback.

“He said he rode up to the top of a hill and took one look back before riding on,” Robert said.

Somewhere, he hooked up with a circus.

“My grandmother said that particular circus wasn’t a respectable one,” Evette said. “My grandfather was a boy fending for himself and it was a hard life. He crossed paths with the Elder Family Show in Galveston and life started turning for the better. The show traveled through Texas an Arkansas.”

To this day, Robert is hesitant to repeat his father’s stories.

“The things he remembered about the way they sometimes had to live off the land as they were moving about and a lot of the things he did as a young man are so fantastic to me I wouldn’t want people thinking I was making up tales,” Robert said.

Two images he does speak of relate to Canada.

“All he had when he left was a horse,” he said. “If he was 14 when he left home, that makes in 1912. When I think about his story of leaving I think about that image of a cowboy from old westerns, silhouetted on his horse up on a ridge, taking a last look back.”

Years after settling at Sugar Hill, George married Morene Brownlee. Born in 1915, she was an orphan who lived with various family members before marrying Mr. Holt, said granddaughter Evette. The first of their four children, Willie D. was born in 1935.

“The other story about Canada – right after they married my dad wanted to take her to meet his family. They hitch hiked to the Canadian border, then couldn’t get across,” Robert said. “All they could do was turn around and come back.”

Evette echoes that same account.

And then there’s the elephant, a thing about which Robert refuses to go on record.

Al Riddle has no such hesitation. His grandmother Gussie told him about it.

“The story she told was that George Holt played the drums and took care of the elephant,” Mr. Riddle said. “He may even have shown up with the elephant. There were wagons that traveled with the show and when they’d get bogged down in the mud, George hooked up the elephant to pull them out. And if that didn’t work he’d get it to back up against the wagon and push. She said it could have moved a house.”

There’s a tale about the elephant crossing the Red River.

“There was a ferry but the ferry operators wouldn’t let the elephant aboard,” Mr. Riddle said. “So George swam with it across the river.”

Evette tells more.

“They used the elephant to pull up the tent,” she said, then laughed. “If Uncle Robert’s around when I tell that story he always demands to know what happened to the elephant.”

There are soft edges to the tale.

“The way I understand it, the Elders were all about music and dancing,” Mr. Riddle said. “They were entertainers. More than once when they were setting up in some new place they found themselves competing with a traveling medicine show. The man running that show complained about the competition – they solved it by combining forces.”

The story of the Sugar Hill families associated with the show Evette describes as part circus and part musical performance hinges around the flu epidemic that swept the continent in 1918, the year they arrived here.

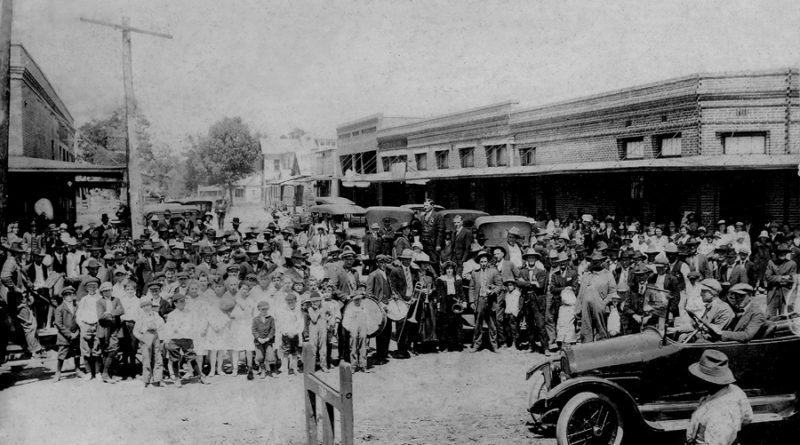

“They’d just come from a show in Sulphur Bluff,” she said. “When my grandmother told me that story she’d always show me the picture that was made there. You can see the performers out in front, the town’s people behind them and the old storefronts in the background.

“The flu caught up with them at Sugar Hill,” she said. “Willie, the younger of the Elder sons, got sick and died. Whatever else happened, his death seems to have broken up the show.”

Time was, Sugar Hill was known as Harris Chapel. Pad Harris, a prominent citizen, was said to have had a herd of horses running free in the untamed land between White Oak Creek and the Sulphur River.

The late Burton Harris wrote about a branch of the Harris family in a novel of historical fiction, The Man Who Disappeared. Set in the prohibition era when Sugar Hill became infamous for production of corn liquor, as the title of his book suggests, Mr. Harris’s account was of an ancestor who vanished during that time.

Pad Harris’s daughter, Paddie, married a local farmer named Buck Blalock. When she died in the flu epidemic, Gussie Elder moved in with Buck to care for their surviving children, Evette said. They married shortly after.

“My mother, Rose, was one of Gussie and Buck’s children,” Mr. Riddle said. “My dad was one of the guys down on the creek making whiskey and when my mom was 15 she ran off and married him.”

Buck Blalock, he said, promptly showed up at Mr. Riddle’s still.

“He made it plain that no daughter of his was going to be married to a moonshiner,” Al Riddle said. “He gave him a team of mules and however it was that he made it stick, he turned daddy into a farmer for a while.”

With the beginning of World War II, Mr. Riddle traded farming for life as a trucker, hauling munitions from Red River Army Depot.

“Those years are some of the best memories of my life,” Mr. Riddle said. “My mom would go off on the truck with my dad so I moved in with Buck and Gussie. I’ve never known a happier family. I spent a lot of time with George Holt’s oldest son.”

George Holt earned his living cutting logs. Robert, his second son, remembers his father filing a bevel on his axe then honing the edge with a whet rock. He remembers the year his father bought his first chain saw. He was in the ninth grade.

“My dad showed up at school one day,” Robert said. “He didn’t say anything to anybody but me and he just signaled for me to come on. The saw had a long bar with a handle out on the end. It took two people to run it – one on the engine and the other out on the bar.”

At 17, Robert Holt left Sugar Hill to join the military. He worked in a motor pool. Coming home, he opened Holt and Son Transmission Shop.

After World War II, Al Riddle’s family moved to Dallas where his father’s connections to trucking later landed him work as a truck driver. He became vice president of a trucking firm before establishing his own trucking company and then moving into brokering loads.

Now retired, he moved back to Titus County 10 years ago.

Evette’s father, Willie D. Holt, aka “Chainsaw Willie” became something of a local legend as a man who sculpted with a chainsaw.

“Willie D and I were the same age,” Mr. Riddle said. “The Holts were people who knew the woods. Even when he was a boy, Willie D knew ‘The Bottom’ like he knew the back of his hand and he loved hunting more than working. When we’d go squirrel hunting his dad would give him five 22 shells. He was expected to come home with five squirrels and if he ever didn’t, I don’t remember it. He didn’t miss.”

A contemporary of George Holt, Friebert Anschutz joined the Elder Family Show in Houston, Evette said.

He married Bennie Elder, the youngest of the three Elder daughters.

“Aunt Bennie was the community midwife,” said Evette. “She delivered my dad, my aunt and my uncles.”

Others among local descendents related to those who came with the Elders are Randles and Limbocks. Tony Anschutz is the oldest of the family still here, Evette said. The youngest is Lexa Lytle, 6 months.

The tale of the Elder family is one of any number of accounts of Sugar Hill, a place that for years has intrigued writers. A story told largely in photos, the 1970’s Between the Creeks describes a tight-knit community of people living close to the land. In his book The Doctor Who Looked at Hands, Dr. John Ellis wrote of the relationships of diet and lifestyles.

If he’s reluctant to speak of the too-fantastic accounts of his family, Robert Holt readily discounts the common belief that his community came to be known as Sugar Hill because of the volumes of sugar sold to moonshiners needing it for distilling corn whiskey.

“Daddy told a story of a boy who lived down at the edge of ‘The Bottom’ and courted the daughter of a prominent family,” he said. “When he’d go to see her in the evening his daddy always ribbed him: ‘Going up on the hill to get some sugar?’” the father would ask.