Secret Cold War military lab embedded at steel plant

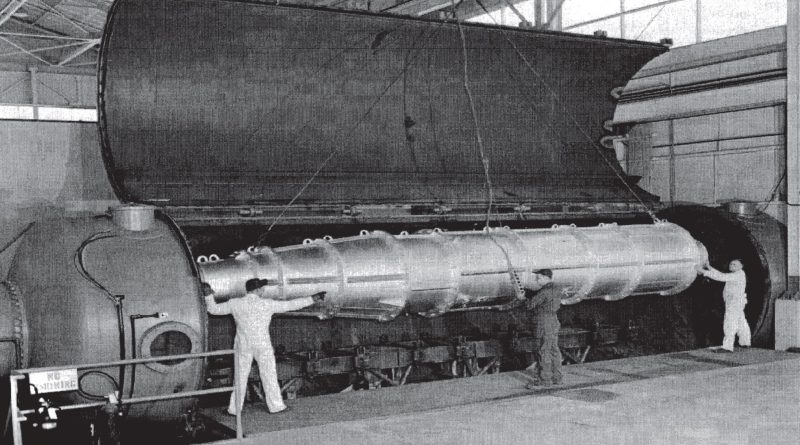

LONE STAR – Known as “The Daingerfield Project,” evolving military technology during the Cold War arms race streamed from an experimental Navy facility opening here in 1945, secured within a compound behind the gates of a state-of-the art government funded steel plant built during World War II. Research involved wind tunnels creating airflow at supersonic speed and compressing air released through nozzles to create thrust. Data gathered here contributed to the Mercury space flights, development of missile guidance systems and the early “ramjet” propulsion technology that drove flight beyond the speed of sound. It was the air compressor systems associated with blast furnaces at what was to become Lone Star Steel that landed research for the Johns Hopkins University “Bumble bee” project here.

Dr. Merle Tuve had become famous in Washington military circles for organizing physicists and engineers as a research group assisting the war-years defense effort. As the Allies took control of battlefields of the second world war, those among the academicians whose work had anchored the soaring capacity of a military-industrial complex became increasingly reluctant to openly work advancing weapons technology, J.E. Arnold wrote in an unpublished memoir.

Mr. Arnold directed operations of the Ordnance Aerophysics Laboratory (OAL) here for 23 years. The aerodynamics wind tunnel closed in 1957. The jet engine propulsion testing facility closed in favor of facilities built closer to Washington as the nation closed on the 1969 launch of man’s first flight to the moon. “Dr. Tuve’s group had been organized in Baltimore as a part of Johns Hopkins University,” Mr. Arnold said. “The board of regents was happy to have a think tank aboard with the provision that there would be no military test facilities located on campus.”

The European Theater of the war had ended in May, two weeks after Mr. Arnold was sent to Texas to tour the idle government steel plant at Lone Star. Before his experimental facilities were opened in 1946, the war in the Pacific was over and the government sold the facilities that became on the dollar,” Fred McKenzie wrote in his history of the company. Mr. Arnold had been a professor of aeronautical and mechanical engineering for ten years before leaving Tulane University in New Orleans for the San Diego division of Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation (CVAC).

There, he coordinated work with a former head of Aeronautical Engineering from Warsaw University and a Montana State College math department head to develop auto-pilot capability for military bombers before CVAC’s military contracting connections landed in Dallas in April of 1945. “This was during the war rationing years,” Mr. Arnold wrote in May of 1995. “Very little in the way of automobile tires, gasoline and oil was available to the public. Before I got to Daingerfield I was lucky enough to get into a station to fix the first two flats I had on the old car I’d rented in Dallas. A few miles from the plant, the third blew without warning.”

Money for the work at Lone Star was channeled through the Navy’s then Bureau of Ordnance to the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) Dr. Tuve’s team had pulled together through Johns Hopkins. Given priority just beneath research on nuclear weapons, the program’s funding bypassed prerequisite congressional approval. “The Navy devised a new procurement contract called ‘Section T’ under which the Johns Hopkins administration and its subcontractors were funded quickly to get the program running,” Mr. Arnold said.

As he’d been told, Mr. Arnold found what was needed in Texas. “The steel plant’s blast furnace blower and steam generating plant provided nearly four times the capacity needed to build the biggest wind tunnel on earth,” he said. “The designers had purposely overbuilt in case they wished to convert their facility to electrical generating.” He had one final meeting with the Navy and the Johns Hopkins team led by Dr. Tuve before flying back to San Diego to report to the company that became prime contractor for the work. He told them the guided missile business “appears to be a coming thing.” Made manager of the Daingerfield Project the next day, he was instructed not to recruit staff from San Diego.

He pulled his engineering teams from company facilities in Kentucky and Pennsylvania. The Fort Worth division wouldn’t let him recruit, but let him borrow personnel during the startup phase. They rented rooms where the Wildflower Inn stands now, a place called the Y Courts at the junction of Texas 11 and U.S. 49 in Hughes Springs, 12 miles from the plant site. “The courts were owned by a retired Master Sergeant called Smitty. The restaurant’s steaks were great but the rooms weren’t air conditioned,” he said. Accountants in the San Diego office complained when he began renting worker apartments on his expense account. “They were bewildered until the concept of the Section T Contract was evident to them, then it all worked out,” he said. He hired 25-year-old Al Eaton away from the California Institute of Technology where he’d been employed as a researcher after graduating with a master’s in aeronautical engineering. “His early interest had been wind tunnel designs,” Mr. Arnold said. “When he came to the Daingerfield Project he had become interested in nozzle designs required to provide thrust at supersonic speeds.”

That was 1945. When he died in 2011, Al Eaton’s obituary described him as the “pioneer whose designs formed the basis for modern guided missile weapon systems.” In a story told in Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Mr. Eaton’s breakthrough came on an evening beginning at a “bar in Texas.” Early test flights of the first APL Supersonic Test Vehicle resulted in discovery of an uncontrollable roll at supersonic speeds, an anomaly “that led to flight failures and nearly terminated the Daingerfield Project.” Primed in an un-named Texas bar somewhere near the experimental facilities that night, “Al worked out the mystery on a number of cocktail napkins then called and woke up his colleagues to meet him in the middle of the night at the wind tunnel. They began modifications at once and after several flight tests, it became apparent that predictable roll control could be achieved through tail rather than wing controls.”

Beyond space flight and missle systems, data collected through 42 successfully tested projects here inadvertently provided mankind with WD- 40. “It stood for ‘Water Displacement, 40th test,” said A.D. Currey, who began working in the secret facility in 1957. “Moisture affected operation of the wind tunnels so we were always looking for solvents to clean the walls. We tried using everything up to and including base formulas for insecticides. The guys in the lab were always working to improve whatever we used and WD-40 was the 40th test.” Growing up on a Cass County farm made Mr. Currey a prime candidate for aircraft maintenance and repair when he went into the military. “The way it was at home, everybody grew up learning how to fix what we broke,” said Mr. Currey, whose military career included notable brushes with history. He worked on restoration of the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic weapon detonated over Japan in World War II. He was a Forward Observer during nuclear tests at White Sands. “In the flash the second before we saw the bomb detonate, I could see the skeleton of the man standing in front of me,” he said.

After the military, he came back to Cass County and briefly operated a gas station before continuing aviation-related work and education in the private sector. There wasn’t an opening when recruiters presented his work history to the Daingerfield Project corporate oversight offices then located in Fort Worth at what had become General Dynamics. “They didn’t have an opening at that moment at the Daingerfield Project but they had a slot for a plumber in Fort Worth so they hired me as a plumber and immediately transferred me to the OAL lab at Lone Star,” he said. He learned quickly enough to ignite the fuel stream channeled through propulsion nozzles of prototype scale models. “My boss joked that he didn’t care who I was or what job slot I was assigned as long as I could consistently make a flame burn at 3,500 degrees,” Mr. Currey said. The sticker on his windshield and his OAL badge got him through the steel company gates in the mornings.

Not allowed outside their designated area, OAL employees were channeled directly to a second security gate opening into the secret test facilities. “The first thing that was different than any other secure area on a military was being behind the gates of a publically- held company making steel,” he said. “We were then behind a second locked gate and nobody without credentials came past our guards. The thing that was really different was the first time I saw a fuel truck back into a blacked out bay where we opened up the area under a false floor in the tanker and unloaded a rocket engine.”

The 33 pages of Mr. Arnold’s foot-noted memoirs are backed by twice as many pages of photographs and documents declassified over years following the closing of the Daingerfield Project in 1968. While the clandestine nature of the work being done behind gates at Lone Star became an open secret the night a fuel leak set off an explosion that was heard for miles around when it blew the roof off the ramjet lab, it had ended more than two decades before Mr. Arnold wrote his memoir.

At its height, the Daingerfield Project employed 373 physicists, scientists, engineers and technicians. The labs also tested prototypes developed by military contractors from Australia, Canada and England; for the Department of Commerce and the National Aeronautics Apace Administration. After the Daingerfield Project closed, Mr. Currey continued working in General Dynamics aerospace labs until retiring.

Fascinating story. Had no idea top secret rocket experiments were being conducted at Lone Star decades post WW2. Great research.